The U.S. Bird Banding Laboratory: an overview of its history and current practices

The North American Bird Banding Program exists today because of a long and rich history of bird banding/marking in the United States and Canada and data from banding is now crucial to the research and management of birds across the continent. This article delves into the history of bird banding in the U.S., how the Bird Banding Lab functions today, and the objectives and goals set for the future.

As of November 2023

History of Bird Banding in the United States of America

Bird banding and marking in the United States of America has a long and rich history. The first notable scientific marking of birds occurred in the early 1800s when John James Audubon tied silver thread around the legs of Eastern Phoebes (Sayornis phoebe) nesting on his farm in Pennsylvania and noticed that the same birds returned the following year (Wood 1945). While these early markings led us to better understand avian habits, it was not until the early 20th century that bird banding began to resemble the modern-day formalized bird banding system. The first use of systematic marking was in 1902 when Paul Bartsch of the Smithsonian Institution banded Black-crowned Night Herons (Nycticorax nycticorax) (Figure 1) in Washington, D.C. with metal bands inscribed with a serial number and a message – “Return to Smithsonian Institution.” Just a year later, Bartsch received his first reported sighting after one of his banded herons was found in Maryland (Wood 1945). This method of banding and receiving reported sightings is still used today.

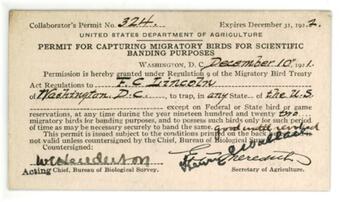

The Formation of a Federal Bird Banding Program

Paul Bartsch’s initial banding effort was followed shortly by the initiation of banding operations discretely dispersed across the continent, led by biologists and conservationists including Percy Taverner, Jack Miner, and John Watson, as well as small groups like the New Haven Bird Club (Wood 1945). Leon Cole, a biologist, geneticist, and member of the New Haven Bird Club, proposed to banders to leave behind sporadic attempts at banding and suggested instead that banders organize and apply a more systematic effort. Cole was the author of seven papers promoting bird banding in the early 20th century and, in 1909, the “father of American bird banding,” became the president of the newly formed American Bird Banding Association (ABBA; Cole 1922, McCabe 1979). The ABBA provided broad guidance and organization of bird banding research across the country and supplied serial numbered bands to bird banders, setting a precedent for overarching and consistent management of bird banding field techniques and data collection (Wood 1945). Over the next decade, however, in the midst of World War I, private support for bird banding dwindled. Following the enactment of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, which prohibited the killing, capturing, selling, and trading of migratory birds (16 U.S.C. 703-712), the U.S. established a federal program to manage bird banding in the U.S. (Wood 1945, Tautin 2016). The U.S. Bird Banding Office was established in 1920 in Washington, D.C. within the Bureau of Biological Survey (then part of the U.S. Department of Agriculture) to support the collection, archival, management, and dissemination of information from banded and marked birds. With the building of a more stable federal program, the ABBA was dissolved, and all bands and archives were turned over to the newly formed Bird Banding Office managed by Frederick Lincoln (Wood 1945, Tautin 2016). Three years later, in 1923, the U.S. and Canada joined forces to create and administer the North American Bird Banding Program (NABBP), aiming to bolster the success of a program documenting bird movements unimpeded by international borders.

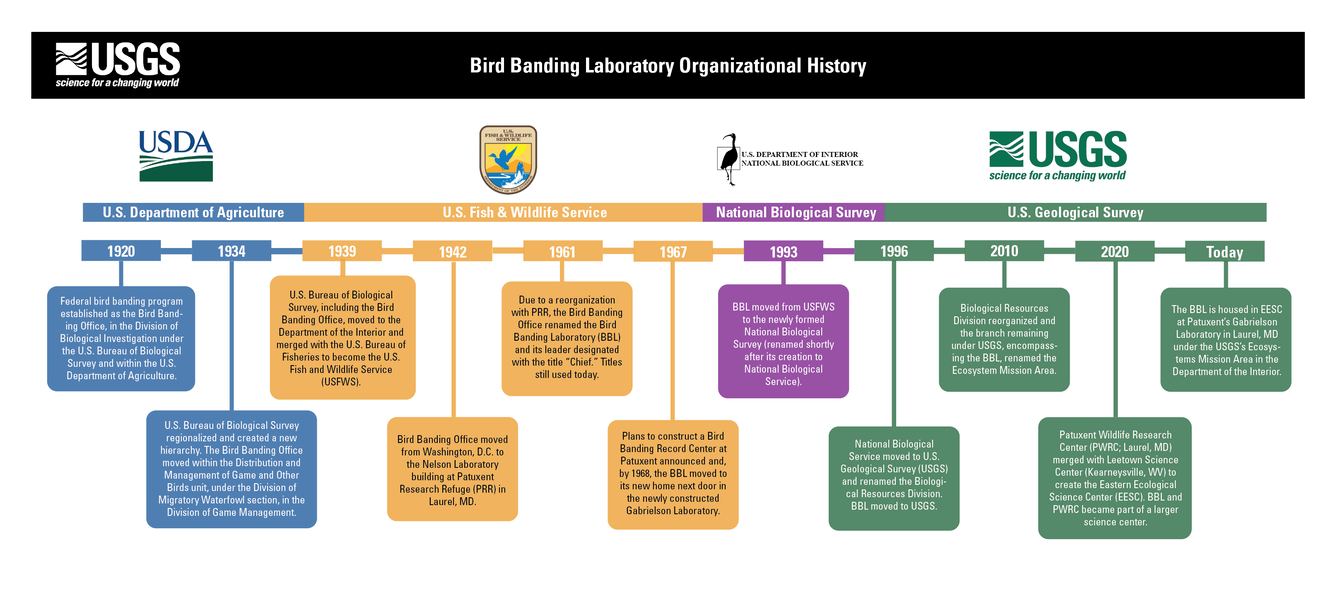

Frederick Lincoln’s tenure as leader of the Bird Banding Office provided the foundation and direction for the NABBP as we know it today. While much of early bird banding had focused on its value in informing patterns in bird migration, Lincoln believed that the information derived from systematic bird banding could inform broader scientific research and, most importantly, bird population management (Lincoln 1921). In one of his published works on bird banding, Lincoln stated: “In the entire history of American ornithology there is probably no single subject that has shown such remarkable development as the method of study carried on through the medium of numbered bands (Lincoln 1928)”. Lincoln led the Bird Banding Office through 1946; developing a band numbering system; recruiting banders; developing guidelines; authoring banding manuals, journal articles and bird bander communications called Bird Banding Notes; developing record keeping procedures; and cultivating international relationships (Tautin 2005). As part of President Roosevelt’s “decentralization” of government offices during World War II, Lincoln oversaw the move of the Bird Banding Office from Washington, D.C. to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Patuxent Research Refuge (PRR) in Laurel, Maryland. The move to Patuxent, housing the Bird Banding Office alongside scientists and statisticians, led the PRR to become an important hub of innovative bird science, research, and management (Tautin 2016). Over the years the U.S. federal banding program has weathered many reorganizations (Figure 2), but one of the most notable changes occurred in 1961 when the Bird Banding Office was renamed the Bird Banding Laboratory (BBL), still its official title. Although the BBL has remained physically housed at Patuxent since its move in 1942, it has sat under the umbrella of the Department of the Interior’s U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) since 1996. In 2020, the BBL became a part of the newly created USGS Eastern Ecological Science Center.

The BBL and NABBP Move Forward

In addition to shifting organizational oversight, the policies and techniques used to guide avian science and study birds through bird banding have changed significantly over the years. While the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 led to the creation of the federal banding lab, the Endangered Species Act of 1973 (ESA) changed many aspects of its purpose and function in avian population management (Tautin 2008). Early in the tenure of the BBL and through the 1960s, waterfowl and other game birds dominated banding efforts. The passage of the ESA, however, refocused avian research efforts to additionally highlight endangered and threatened species and many non-game species in general. By the 1990s, the BBL was again adapting to current scientific need to facilitate broad-scale cooperative and coordinated banding efforts across organizations and locations, both within the U.S. and internationally. For example, in the late 1980s, the BBL helped fund and initiate the Institute for Bird Populations and their Monitoring and Avian Productivity and Survivorship (MAPS) program, which applies a strict banding schedule and mist-netting effort alongside robust analytical models to summarize breeding season data from across North America (Tautin 2008). The BBL further provided infrastructure within the existing permit authorizations to support MAPS banders specifically. In another example, the BBL worked closely with the North American Banding Council (NABC) to develop bander training and certification programs to solidify best banding practices, ethics, and policies (Tautin 2008). Over the past 103 years, the BBL has evolved from cubicles of staffers and administrative assistants once numbering more than 40, to what is now a relatively small team of skilled biologists and programmers (Figure 3) that maintain the largest and longest running database of bird banding and encounter records in the world. The BBL continues to adapt so that it can best support the advancement of avian science, management, and conservation.

Today's Bird Banding Laboratory

The current role of the Bird Banding Lab is extensive and includes: issuing permits and providing federal metal bands for free to all banders; promoting sound and ethical practices and techniques; developing and supplying instructional materials and technical advice; endorsing standardization of data collection and reporting; assisting in the development and coordination of banding projects including the use of auxiliary markers; facilitating communication and information exchange between banders within the U.S. and worldwide; supporting banding associations; encouraging public recoveries and reporting; curating data and serving as the banding and encounter data repository for North America; disseminating data to researchers and managers; promoting bird banding research; and collaborating with partners in scientific investigations to best support the advancement of avian management and conservation science (Figures 4 and 5). Additionally, to keep up-to-date with current banding practices and associated skills, BBL staff have operated a fall migration passerine banding station at Patuxent since 1979 and a breeding season MAPS station since 2017 (Figure 6).

Federal Permitting

The BBL issues federal bird banding and marking permits to banders who are U.S. citizens or operate within the U.S. territory and that need to conduct a scientific study that requires capturing, handling and marking birds. Banders requesting permits need to demonstrate sufficient training and experience relevant to their scientific investigation, as well as provide letters of recommendation from experienced banders. Currently the BBL manages approximately 9000 active permitted banders, including 2000 master banders and 7000 sub-permittees. While sub-permittees have enough experience to band birds without supervision, the master permitted banders are additionally responsible for all operations and activities occurring under their permit, including being accountable for their bands, band inventory and data submissions, as well as the conduct of their sub-permittees. Each permitted bander is provided authorizations by the BBL, specific to species, location, capture technique and auxiliary marking type. The BBL provides permitted banders with uniquely numbered metal federal bands free of charge, tracks the bands assigned to and used by each permit in relation to the BBL band numbering schema, and coordinates the use of auxiliary markers such as transmitters, geolocators, and colored and coded plastic leg bands or neck collars. To maintain their permit, banders must submit banding records on a regular basis, conduct themselves ethically, and justify continued banding and marking efforts.

Database Management

The greatest value presented by the NABBP is in its long-running and curated dataset. Stored centrally, the NABBP database is a repository for all banding and encounter data in North American and currently houses 85 million banding records and 5.5 million encounter records (as of July 2025), including both encounters reported by the public and recaptures reported by bird banders. Between the U.S. and Canada, NABBP staff process and vet approximately 1.2 million banding and 150 thousand encounter records annually, as well as maintain reference tables and data filters that require frequent updates and are often species-specific (e.g., expected wing and tail measurement ranges). All this data curation is provided with the goal of disseminating these data to scientists and the public and to ultimately use these data in the development of informed management and conservation science practices. As an office of the federal government, the BBL provides open access to the dataset and responds to numerous data requests each year from federal and state agencies, graduate students, researchers, non-profit organizations, and members of the public. The NABBP dataset has been used to study avian behavior, document migration and movement patterns, monitor gamebird populations and inform hunting regulations, examine avian and human health issues (e.g., West Nile Virus or Avian Influenza), identify hazards and environmental disturbances to birds (e.g., airports, cats, hurricanes, cold snaps, etc.), and manage habitat for endangered species (Tautin 2008, Buckley 1998). The application of the NABBP dataset to avian science is vast and wide-reaching.

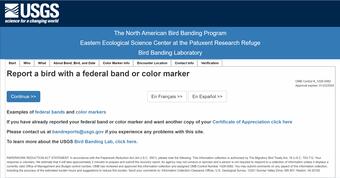

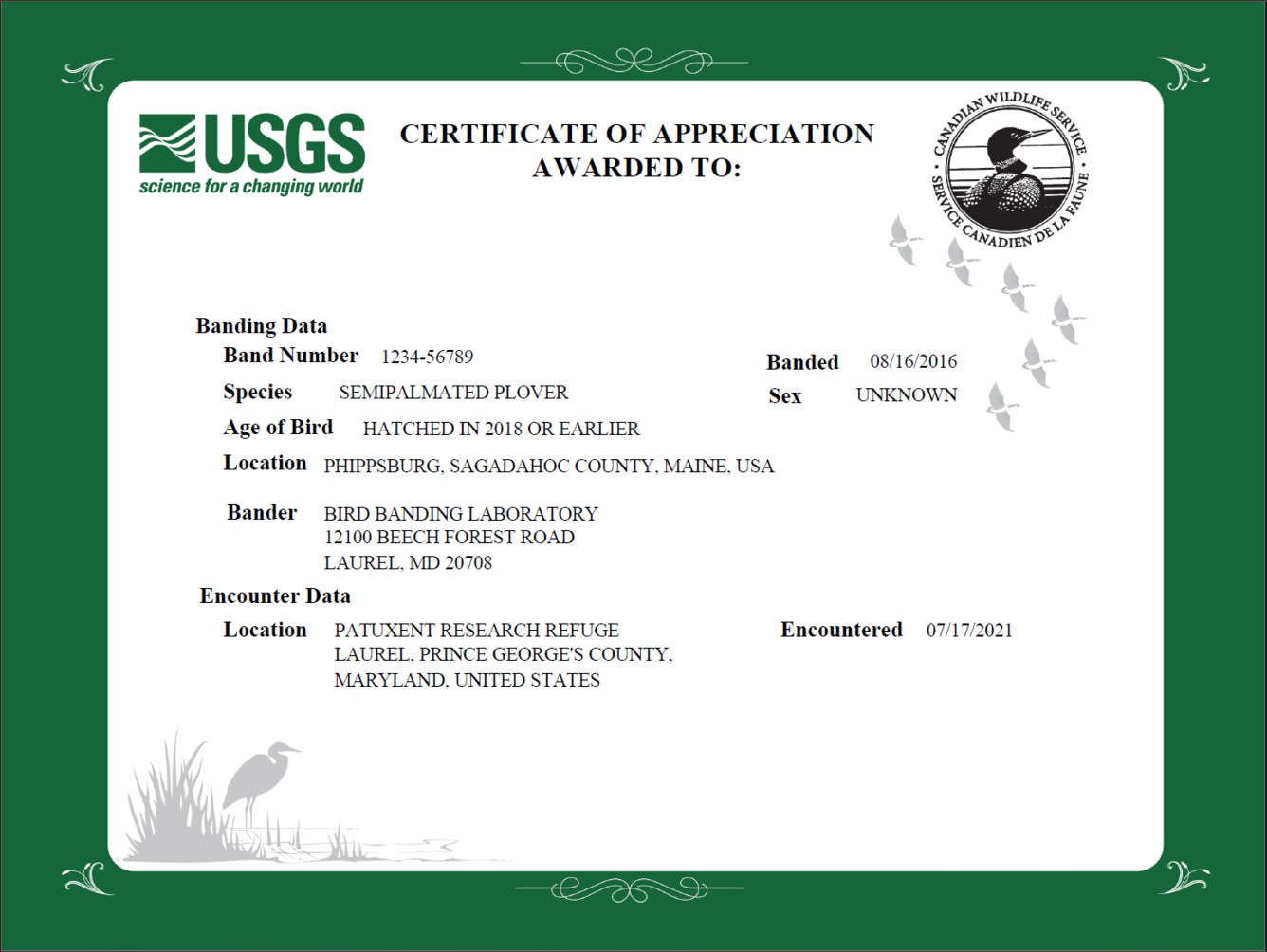

To ensure the completeness of the NABBP database, and fulfill the requirements of their banding permit, banders must submit their banding and recapture records to the BBL through an online application, the Bander Portal. Through this portal, banders can also review and update their band inventory, request modifications to their permit, and retrieve data. The portal was developed relatively recently (2018, updated to allow data submission in 2022) and, although a welcome upgrade for permitted banders, is not available to members of the public as a data submission tool. Birders, photographers, and hunters can instead report their encounters with a banded or marked bird through our website www.reportband.gov (Figure 7) and these reports contribute approximately 80,000 encounter records to the NABBP database annually. Once a report has been vetted, finders receive a Certificate of Appreciation (Figure 8) from us with some of the original banding details (the confirmed species, and when and where it was banded). To many reporters, this is a prized possession.

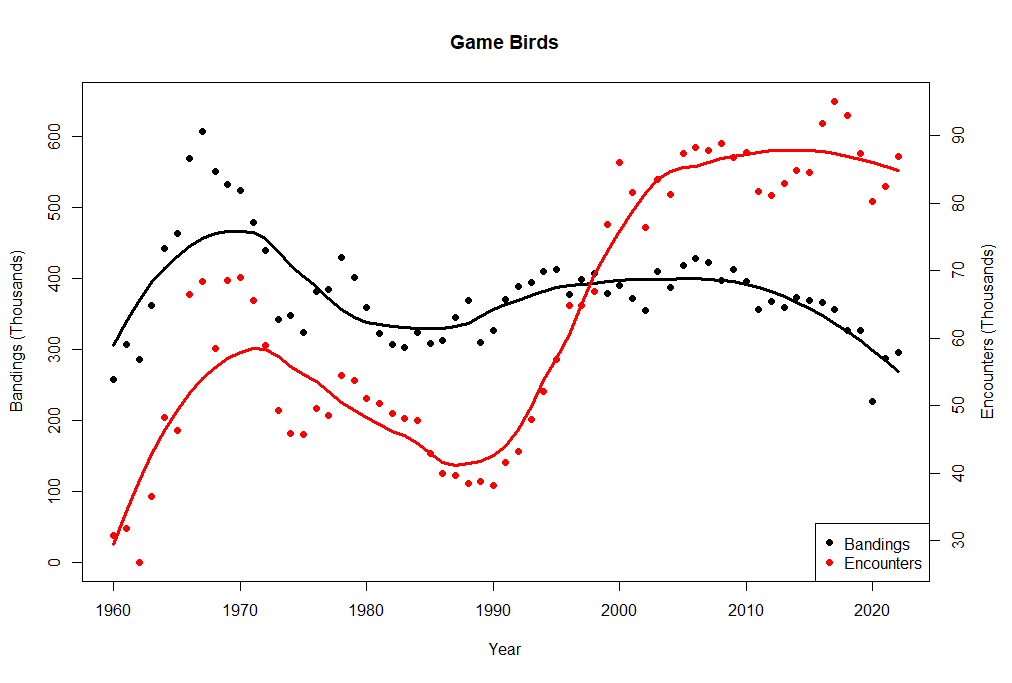

Adapting to Change: the BBL's Evolving Infrastructure

Over the history of the BBL, we have been challenged to rapidly adapt to evolving scientific inquiries, science needs, technologies, and partner needs, all while navigating funding instabilities and variable staffing levels. Frequently, updates to BBL services and infrastructure must be made swiftly and with little notice. Even gradual changes, such as in the number of annual banding records, become substantial over time and have pushed the BBL to make large shifts in policy and procedure. As the number of banding records have increased, so have the number of resightings (Figure 9), and additional new challenges such as replacement bands and new data fields have led to accommodations within the database structure. The BBL’s demonstrated ability to readily adapt is one of its greatest strengths.

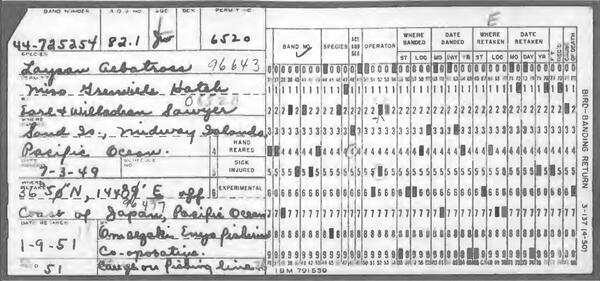

In the first years of the BBL, banding and encounter data were collected through the mail and catalogued in filing cabinets. Early on, it was recognized that a paper-based system was not sustainable considering the number of reports and, in 1929, the BBL began utilizing IBM punchcards (Figure 10) to organize and store banding and encounter data for birds that had been resighted. In 1959, a fire at Patuxent damaged many punchcards, highlighting the vulnerability of paper records and motivating the BBL to capitalize upon technological advancements and computerization by the early 1960s (Houston et al. 2008). It was not until 1995 that the BBL offered a toll-free phone number for the public to report band encounters, increasing the rate of waterfowl reporting by hunters from 32% to 80% (Figure 9; Nichols et al. 1991, Tautin 2008). Later, the advancement of the internet led to the launch of www.reportband.gov in 2000, a website for the public to report encounters with banded birds to supplement and eventually replace the toll-free number. The possibility of electronic and remote data submission also allowed for the development of banding data submission tools, including Band Manager (1999) and BandIt (2006) and prompted the shift from a hierarchical to a relational database. In 2022, the BBL moved away from software-based data submission and released the updated Bander Portal with web-based submission capabilities. The BBL has recently invested in further modernizing our IT infrastructure to better allow us to rapidly adapt to evolving stakeholder and partner needs, including expanding functionality to the Bander Portal, relocating to remote data servers, and modernizing the coding of our websites and database.

In addition to technological advancements in data management, bird banding and marking today encompasses technologies not heard of 100 years ago. Banders now frequently supplement traditional bird banding with auxiliary markers to increase the possibility of resightings and add various transmitter types for long distance tracking. Furthermore, banders sample and collect data from birds using new and modern techniques, such as the collection of blood and feather samples for DNA analysis (Tautin 2005). This shift in data collection by banders has necessitated structural changes to the NABBP database (e.g., additional ancillary fields) as well as updates to data management practices. In 2010, the BBL updated the public reporting site reportband.gov and modified the database to accommodate reports of auxiliary-marked birds, e.g., colored markers/bands, allowing for both automatic and manual matching of public reports to individual bird banding records within the database. Although with the advancement of technology the NABBP has further updated the database to allow banders to indicate birds marked with geolocators, PIT tags, and transmitters, the database is currently not able to archive the data produced from the additional marking technologies. Canada has recently required their permit holders to store their bird tracking data in a third-party repository, such as MoveBank, and the BBL is currently reviewing their data management guidelines to develop recommendations for banders in the United States.

Beyond technology and updated banding practices, the BBL must also respond to current factors impacting avian populations, including environmental and health crises. In the case of the recent outbreak of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza, the BBL needed to quickly disseminate updated guidance for safe and ethical banding practices and process a large number of permit amendments, including the addition of sub-permittees and changes to permitted banding locations, to support the immediate large scale disease monitoring efforts across the country. The outbreak also initiated conversations about how the BBL might develop additional infrastructure for future disease monitoring, for example, new permitting authorizations for collecting samples. This case study highlights some of the challenges the BBL faces while aiming to respond to the new needs of our community and from science.

Working With Partners

The BBL supports relationships with a wide range of stakeholders, from federal and state agencies to non-government organizations and universities, as well as individual researchers. We work closely with the four Flyway Councils to further avian science and management. To help promote bander education and training, the BBL collaborates with local and regional banding associations and producers of bird banding guidelines such as the North American Banding Council and Peter Pyle’s Identification Guide to North American Birds. Partnerships with the National Audubon Society and the Smithsonian Institute support the development of new field and analytical techniques for the study of birds. Outside North America, we coordinate with banders and banding programs throughout the western hemisphere with which we frequently exchange data.

The BBL aids many outside groups with their project organization, coordination, and data management. As one example, BBL staff have worked closely with the group of researchers studying populations of Black-footed (Phoebastria nigripes) and Laysan albatross (P. immutabilis) in the Pacific, helping ensure an accurate and complete dataset is available to make informed management decisions (see Pacific Albatross). Most recently, the BBL partnered with National Audubon Society in the development of the Bird Migration Explorer, a webtool that demonstrates bird migration and the connectivity between locations across the western hemisphere using data provided by NABBP. Similarly, the BBL has partnered with the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center and Georgetown University on the Migratory Connectivity Project, a project that seeks to examine the full BBL dataset of banding and encounters across the Americas with the goal to advance the understanding of birds throughout their full life cycle. The BBL has also initiated our own research projects, coordinating with U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and university researchers to analyze encounter data from the NABBP database to reveal the impact of building collisions (see Bird Collision Science). The data from the BBL's fall migration banding station highlights the possibilities for identifying bird population trends using migration data and emphasizes the need for data sharing and collaboration across regions, flyways, and continent-wide.

In addition to fostering agency and organizational partnerships, the BBL encourages the participation of citizen and community scientists. Traditionally, the BBL has largely focused on coordinating with hunters to report the take of banded waterfowl and other gamebirds to inform and enable state and federal agencies to set proper management goals and hunting regulations. However, the recent increase in the use of color markers, advancements in camera technologies, and improvements in color-marker reporting capabilities have made the BBL more accessible and inclusive to bird watchers, photographers, and amateur scientists using apps like eBird and iNaturalist*. Greater participation by the general public enriches our database, better informs management decisions, and fosters public interest in avian science and conservation.

Banders Without Borders

Finding novel ways to approach evolving needs and adapt to changes is at the forefront of BBL operations and planning. Most recently, this past year the BBL launched its Banders Without Borders initiative to open communications with its sister banding schemes around the world and, through this initiative, have been able to share experiences and improve our operations learning from the interactions with others doing similar work (Figure 11). Our goal is to advance avian science and conservation through collaboration. To date the BBL has met with 16 banding schemes representing 13 countries across the globe. This past February, we had the pleasure to meet with the Spanish Ornithological Society’s SEO BirdLife, one of four banding schemes in Spain. It was eye-opening and informative to see how multiple banding schemes coordinate within one country – a strategy that could be implemented by other countries struggling to establish a single unified national scheme as it is with many South American countries. We believe open communication and sharing what we learn will allow for broader western hemisphere coordination. We look forward to adopting many of the innovative approaches our fellow banding schemes employ to meet the needs of their community and hope to share our future successes with our community.

Looking to the Future

In more than 100 years of operation, the BBL and the bird banding community have never stopped learning and adapting (see Scientific American; Figure 12). We continue to learn and develop new study methods as technology advances and new strategies as challenges emerge. The future of bird banding will inevitably be exciting and bring new changes as science and partner needs arise, but the BBL will be prepared. Today, under the leadership of Antonio Celis-Murillo, the BBL has a staff of 15 people, made up mostly of dedicated knowledgeable and experienced scientists in the bird banding sciences. Despite having such a small number of staff in relation to the size of the program, the BBL team bring enthusiasm and the necessary skillsets to ensure that the lab remains the premier resource for long-term bird banding and marking data in North America and becomes a robust, integrated scientific resource that that rapidly adapts to and supports new science needs, study methods, and technologies to facilitate successful and effective bird management and conservation.

Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

This article was translated from the original Spanish publication. Reprinted with permission in English. Citation for original publication:

McKay, J. L. and Walker, L. E. 2023. El Laboratorio de Anillamiento de Aves de EE. UU.: una visión general de su historia y prácticas actuales. Revista de Anillamiento.