Effective Communication in PFAS Research: Moving Beyond "Ubiquitous"

In recent years, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), have gained attention for their environmental presence; however, the term "ubiquitous" used to describe them can be misleading. USGS scientists push to use more precise language such as "widespread" and “commonly detected” to avoid confusion and misinformation. This distinction is crucial for understanding the actual occurrence of PFAS and its implications for public health and drinking water

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) can be found in a wide range of sources, including man-made items such as stain-resistant textiles, nonstick cookware, industrial chemicals, and food packaging. Additionally, they are now widely present in the environment. However, they are not in ALL of the earth's water, soil, and sediment. Yet, the term “ubiquitous” is often used to describe PFAS, which can be misleading.

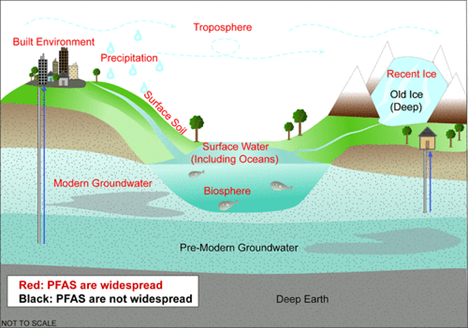

USGS authors bring to light that the term ubiquitous implies that PFAS are found everywhere at all times. While it’s true that PFAS can be found in many places—like the top layers of soil, rainwater, and rivers—this doesn’t mean they are everywhere, especially in some deeper geological layers, groundwater, or very old ice.

PFAS are often detected because they can be released into the environment through their manufacture and use. However, when we look at deeper layers of soil, or ice and groundwater that formed before the 1950s, these areas usually don't show PFAS contamination. Most of the groundwater-based public drinking water in the U.S. comes from ancient groundwater sources that typically lack PFAS unless there was contamination during the extraction process. Research shows that nearly all PFAS found in groundwater today come from newer sources, highlighting that older groundwater is generally free from these chemicals.

Understanding the true nature of PFAS distribution is crucial for several reasons:

- Public Health: Misinterpretations of the ubiquity of PFAS can lead to unnecessary alarm about the safety of drinking water sources. If people believe PFAS are present everywhere, they may underestimate the actual risks associated with contaminated sources and overestimate risks in clean, ancient water sources.

- Environmental Management: Accurate knowledge of where PFAS are found helps regulatory agencies and environmental scientists develop better strategies for monitoring and remediation. If PFAS are primarily a modern contamination issue, efforts can be more focused on current industrial practices rather than older sources of water that are generally clean.

- Policy Making: Policymakers rely on accurate scientific data to make informed decisions about regulations and public health initiatives. Misleading information about the presence of PFAS could lead to ineffective or unnecessary regulations that do not address the real sources of contamination.

- Public Perception: If the public believes PFAS are everywhere, it may lead to fear and mistrust of environmental institutions and the water supply. Clear communication about where PFAS are typically found fosters better understanding and public confidence in drinking water safety.

- Research Focus: Understanding that the majority of PFAS detections are from modern sources can guide future research funding and studies toward newer industrial practices, contamination sources, and the correct environmental matrices rather than directing efforts toward older geological formations that are less likely to be a concern.

Using "ubiquitous" incorrectly heightens public concern about PFAS, making it more difficult for regulatory agencies and decision-makers. Instead, precise terms like "widespread" or "commonly detected" more accurately reflect the prevalence of PFAS and using these descriptors helps stakeholders understand the true risks. These terms convey that while PFAS are not found everywhere at all times, they are frequently identified in various environmental samples. Clear communication is essential for effective public health initiatives that are focused on managing PFAS contamination.

This work was funded by the USGS Ecosystems Mission Area, through the Environmental Health (Contaminant Biology and Toxic Substances Hydrology) Program.

Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substance (PFAS) Core Technology Team

Per-and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) Integrated Science Team

Over a third of groundwater in USA public-supply aquifers is Anthropocene-age and susceptible to surface contamination Over a third of groundwater in USA public-supply aquifers is Anthropocene-age and susceptible to surface contamination

Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances in groundwater used as a source of drinking water in the eastern United States Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances in groundwater used as a source of drinking water in the eastern United States

In recent years, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), have gained attention for their environmental presence; however, the term "ubiquitous" used to describe them can be misleading. USGS scientists push to use more precise language such as "widespread" and “commonly detected” to avoid confusion and misinformation. This distinction is crucial for understanding the actual occurrence of PFAS and its implications for public health and drinking water

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) can be found in a wide range of sources, including man-made items such as stain-resistant textiles, nonstick cookware, industrial chemicals, and food packaging. Additionally, they are now widely present in the environment. However, they are not in ALL of the earth's water, soil, and sediment. Yet, the term “ubiquitous” is often used to describe PFAS, which can be misleading.

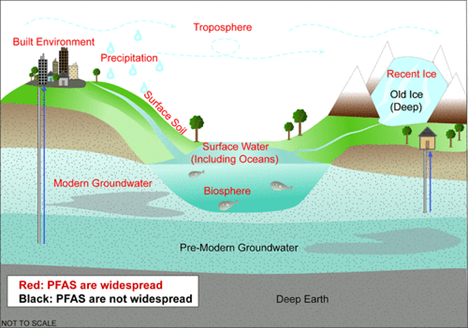

USGS authors bring to light that the term ubiquitous implies that PFAS are found everywhere at all times. While it’s true that PFAS can be found in many places—like the top layers of soil, rainwater, and rivers—this doesn’t mean they are everywhere, especially in some deeper geological layers, groundwater, or very old ice.

PFAS are often detected because they can be released into the environment through their manufacture and use. However, when we look at deeper layers of soil, or ice and groundwater that formed before the 1950s, these areas usually don't show PFAS contamination. Most of the groundwater-based public drinking water in the U.S. comes from ancient groundwater sources that typically lack PFAS unless there was contamination during the extraction process. Research shows that nearly all PFAS found in groundwater today come from newer sources, highlighting that older groundwater is generally free from these chemicals.

Understanding the true nature of PFAS distribution is crucial for several reasons:

- Public Health: Misinterpretations of the ubiquity of PFAS can lead to unnecessary alarm about the safety of drinking water sources. If people believe PFAS are present everywhere, they may underestimate the actual risks associated with contaminated sources and overestimate risks in clean, ancient water sources.

- Environmental Management: Accurate knowledge of where PFAS are found helps regulatory agencies and environmental scientists develop better strategies for monitoring and remediation. If PFAS are primarily a modern contamination issue, efforts can be more focused on current industrial practices rather than older sources of water that are generally clean.

- Policy Making: Policymakers rely on accurate scientific data to make informed decisions about regulations and public health initiatives. Misleading information about the presence of PFAS could lead to ineffective or unnecessary regulations that do not address the real sources of contamination.

- Public Perception: If the public believes PFAS are everywhere, it may lead to fear and mistrust of environmental institutions and the water supply. Clear communication about where PFAS are typically found fosters better understanding and public confidence in drinking water safety.

- Research Focus: Understanding that the majority of PFAS detections are from modern sources can guide future research funding and studies toward newer industrial practices, contamination sources, and the correct environmental matrices rather than directing efforts toward older geological formations that are less likely to be a concern.

Using "ubiquitous" incorrectly heightens public concern about PFAS, making it more difficult for regulatory agencies and decision-makers. Instead, precise terms like "widespread" or "commonly detected" more accurately reflect the prevalence of PFAS and using these descriptors helps stakeholders understand the true risks. These terms convey that while PFAS are not found everywhere at all times, they are frequently identified in various environmental samples. Clear communication is essential for effective public health initiatives that are focused on managing PFAS contamination.

This work was funded by the USGS Ecosystems Mission Area, through the Environmental Health (Contaminant Biology and Toxic Substances Hydrology) Program.