Gas monitoring helps tell the story at Mount Rainier.

USGS scientists conducted airborne measurements of volcanic gases over Mount Rainier for the first time since 1998.

Scientists study many different natural processes to understand what is happing just out of our view inside a volcano. There has been a lot of discussion about the earthquake swarm at Mount Rainier, but earthquakes are only a part of the story. Cascade Volcano Observatory (CVO) volcanic gas specialists recently traveled to Mount Rainier to sniff for clues about what caused the recent seismic swarm

What story does the new gas flight tell about Mount Rainier?

When earthquakes happen near a volcano, scientists need to figure out what’s causing them. They could be related to several things including tectonic activity, the movement of hot water and gases underground (hydrothermal unrest), or rising magma (magmatic unrest). Knowing the cause helps scientists prepare for potential hazards.

Volcanic gas sampling can help reveal the cause of earthquakes in a volcanic system, much like how blood tests help a doctor figure out what’s causing a patient’s symptoms. Scientists know from years of research that hydrothermal gases are typically rich in water vapor (H2O), carbon dioxide (CO2), and hydrogen sulfide (H2S), whereas shallow magma often releases sulfur dioxide (SO2). By identifying which gases are present, scientists can piece together a clearer picture of what’s behind an earthquake swarm.

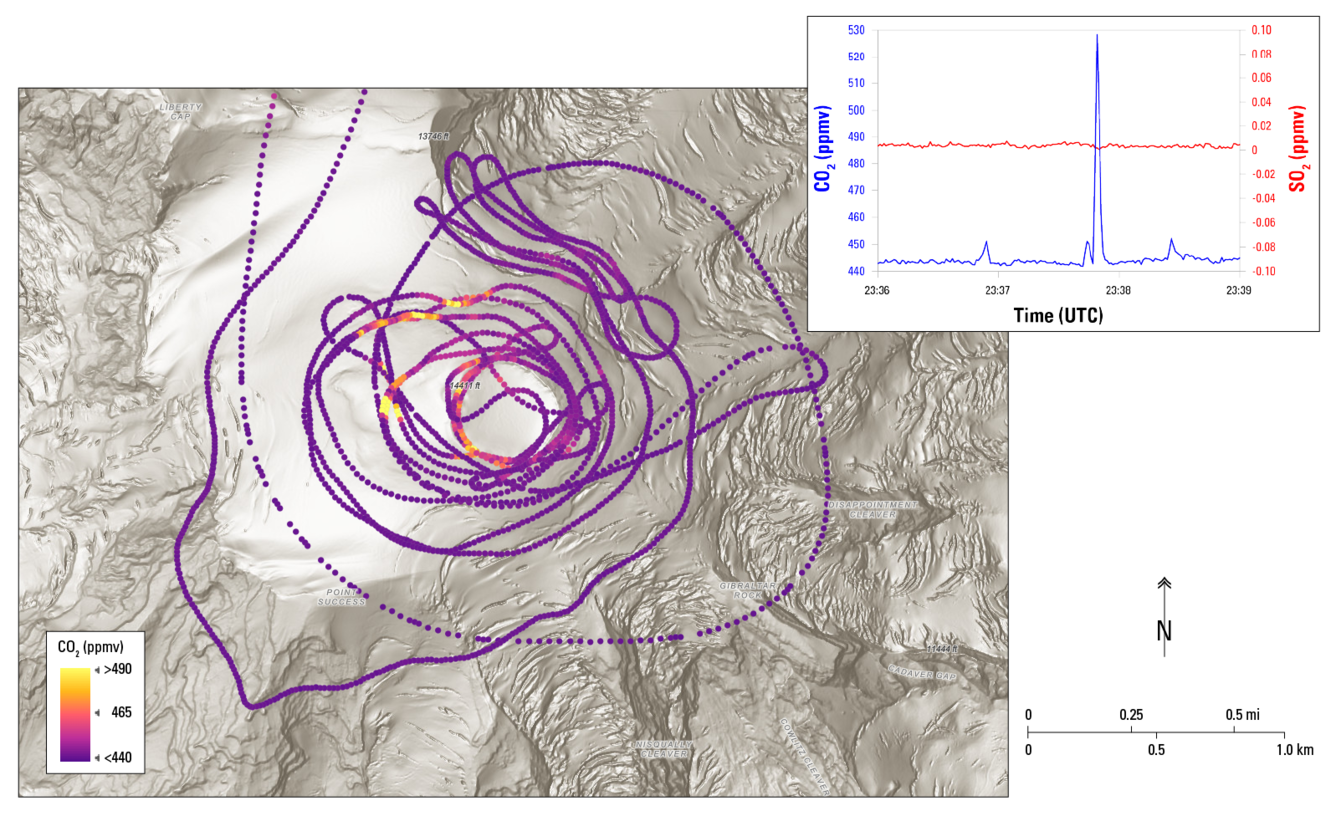

The team saw small gas vents (fumaroles)around the East and West summit craters, similar to what was seen during a gas flight in the late 1990s. The sensitive gas instruments were able to detect small amounts of water vapor and CO2 coming from these vents, but no sulfur-containing gases like sulfur dioxide (SO2) or hydrogen sulfide (H2S) were found.

Overall, the gas released from Mount Rainier’s summit was consistent with low-temperature hydrothermal gas emissions that scientists have seen here before. The gas measurements indicate that despite over 1350 located earthquakes occurring at Rainier in July and August, the volcano’s gas output has not changed much. This suggests the recent seismic swarm was most likely related to changes in the volcano’s shallow hydrothermal system, not by new magma rising. Thanks to the use of highly sensitive gas sensors and close coordination between the USGS and National Park Service, we now have a better understanding of what caused the recent earthquakes at Mount Rainier.

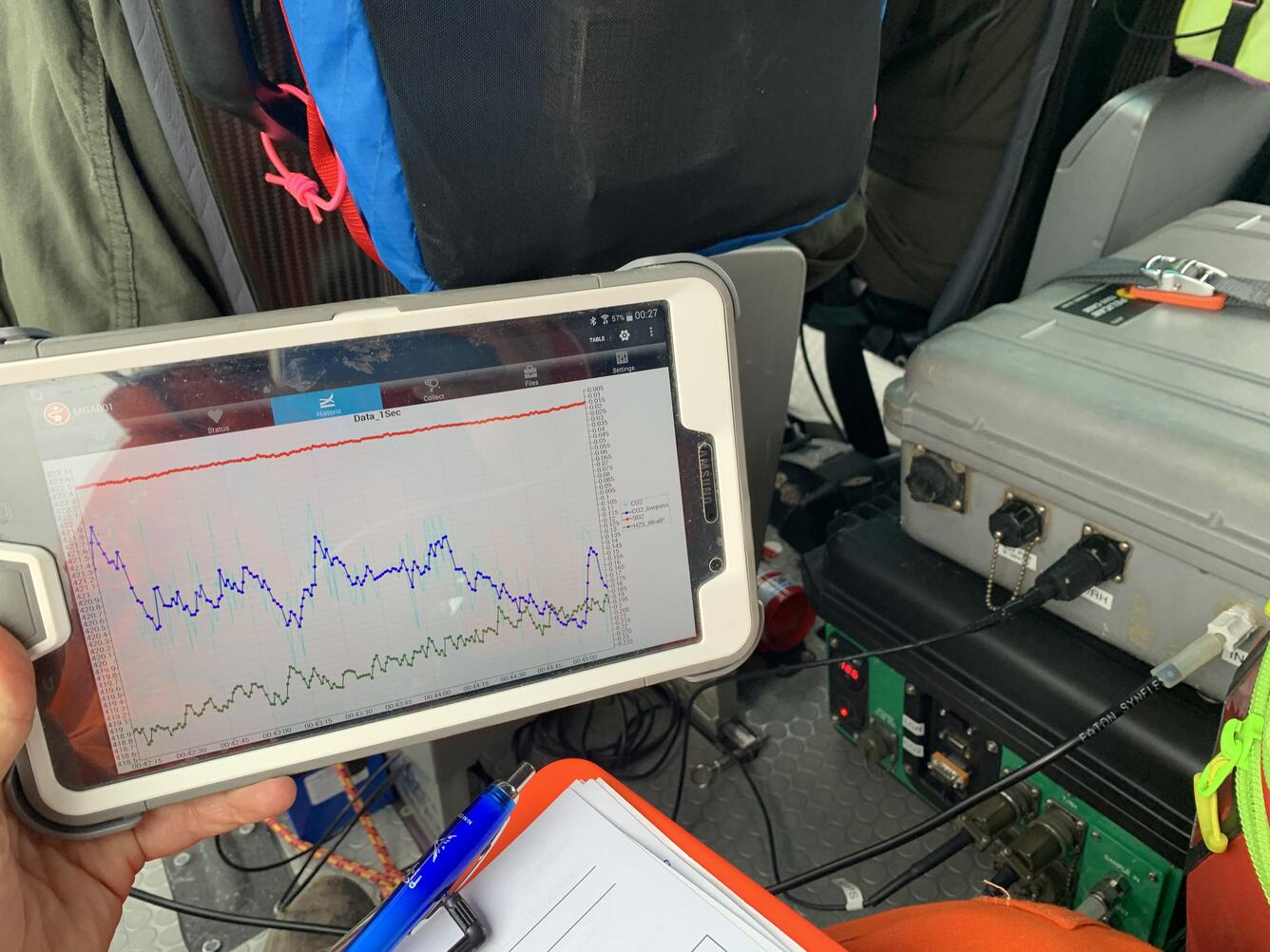

Gas composition data is displayed in real time during gas flights. The tablet display shows measurements of CO2 (blue line), SO2 (red line) and H2S (green line) that are collected every second.

Shaded relief map of Mount Rainier with GPS track from the gas observation flight. The colors correspond to CO2 levels in parts per million by volume (ppmv) that were measured during the flight. Yellow points indicate elevated CO2 levels, which were located near visibly degassing volcanic gas vents. The small inset plot shows example CO2 and SO2 data. Note that clear CO2 peaks (blue line, left axis) were observed as the aircraft passed over visibly degassing vents, but no corresponding SO2 was detected (red line, right axis).

August 4, 2025 volcanic gas observation flight at Mount Rainier

In response to the recent seismic swarm at Mount Rainier, CVO gas geochemists Laura Clor and Christoph Kern conducted the first volcanic gas observation flight at Mount Rainier since 1998. (Note – for more information about the seismic swarm/temporary increase in earthquakes, at Mount Rainier, please follow the link at the bottom of the page.)

The USGS pioneered the use of airborne volcanic gas monitoring with helicopters and fixed-wing aircraft during the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens. Since then, scientists have continued to develop innovative new tools and techniques to keep tabs on restless, difficult to access volcanoes across the US. When scientists collect gas measurements during flights over volcanoes, the data helps them understand what’s happening inside the volcano and what hazards might be present. They share this information with emergency managers, who use it to plan safety measures so communities can be prepared if activity increases.

Photo: USGS gas geochemists Christoph Kern (left) and Laura Clor (right) during the airborne gas survey of Mount Rainier.

How is a gas flight conducted?

For the gas flight at Mount Rainier, the USGS coordinated with Mount Rainier National Park to use a powerful A-Star helicopter that can fly at high altitudes. The helicopter is usually used for wildfire response and high-elevation search and rescue in the Park, but on the afternoon of August 4, USGS scientists equipped it with volcanic gas monitoring equipment. This included upward-looking ultraviolet (UV) spectrometers and a collection of infrared and electrochemical sensors for the detection of water vapor (H2O), carbon dioxide (CO2), sulfur dioxide (SO2), and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) gases. A specially designed plate mounted in the helicopter’s window featured sensor mounts and gas inlets that allowed ambient air from outside the aircraft to be carried through tubes to the sensors inside.

The flight started above the volcano’s 14,411 foot-high summit and spiraled downward past the upper slopes of the mountain, sampling gases and observing gas vents along the way. After descending to about 13,000 ft and circling the mountain, the flight returned to the summit for additional observations before returning to the heliport.

More about the Mount Rainier earthquake swarm:

An earthquake swarm began at Mount Rainier, Washington, at 1:29 a.m. PDT (08:29 UTC) on July 8, 2025. An earthquake swarm is a cluster of earthquakes occurring in the same area in rapid succession. Currently, there is no indication that the level of earthquake activity is cause for concern, and the alert level and color code for Mount Rainier remain at GREEN / NORMAL.