How does water from snow and rain get to the numerous hot springs in Yellowstone?

Water molecules (H₂O) are made of two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom, but these atoms aren't always the same. Tracking how these atoms in water molecules differ is a powerful tool for tracing where snowmelt or rain seep into the ground, how water flows beneath the ground, and how long does water flow until the arrives at a hot spring.

Yellowstone Caldera Chronicles is a weekly column written by scientists and collaborators of the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory. This week's contribution is from Shaul Hurwitz, research hydrologist, and Blaine McCleskey, research chemist, both with the U.S. Geological Survey.

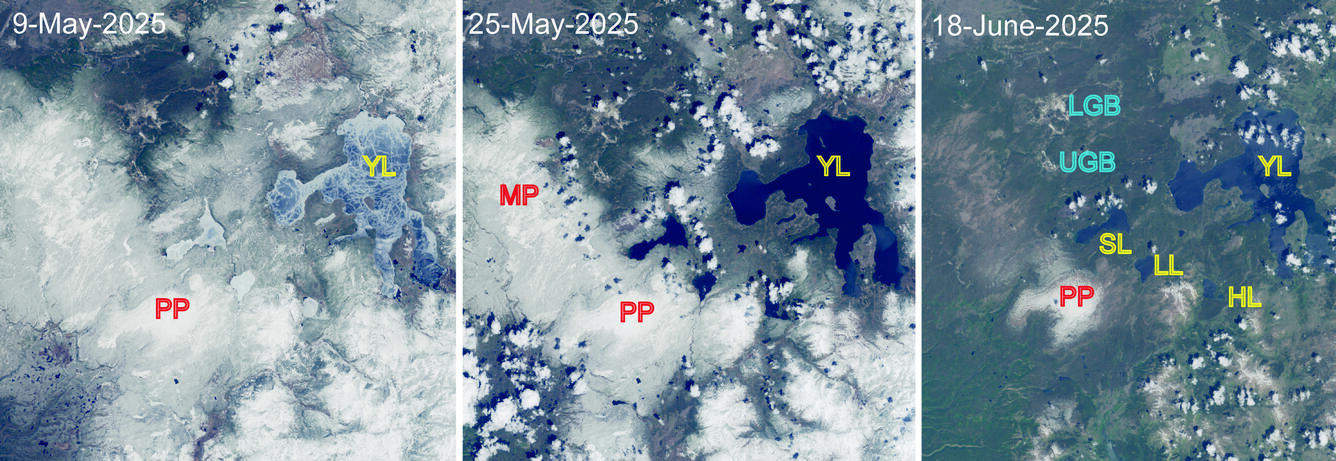

A lot of snow and rain fall on the Yellowstone volcanic plateau, especially between November and May. The snowpack is typically ablated (removed from the ground by melting, evaporation, sublimation, or wind and avalanches) by May in the lower elevations, and by June at higher elevations. Much of the snow and rain fall on the Madison and Pitchstone Plateaus in the southwestern parts of Yellowstone National Park. On these plateaus, the large amounts of winter snow are a result of moist air masses from the west that are forced upward when they encounter these plateaus, a process called orographic lift. To the east and northeast of the Madison and Pitstone Plateaus, typically lower amounts of snow and rain fall.

Most of the water from precipitation that falls in the volcanic plateau ends up in Yellowstone’s rivers, mainly following snowmelt in May and June. However, some of this meteoric water is recharged into the ground and is then called “groundwater.” After flowing for some distance this groundwater can be erupted from Yellowstone’s geysers or flow out of the hot springs. But what path does the water follow, and how long does this journey take?

A water molecule (H2O) consists of one oxygen (O) and two hydrogen (H) atoms. Each of these atoms has several isotopes, meaning that they have the same number of protons but different numbers of neutrons and thus different atomic masses. In the laboratory, these differences in mass can be measured precisely. One of the most important ways scientists track the movement of water is by fingerprinting the water in different reservoirs (snow, rivers, hot springs, etc.) through the relative abundance of different hydrogen and oxygen isotopes, and the concentrations of tritium, which is a rare and radioactive isotope of hydrogen. Because tritium decays radioactively, its concentration in water decreases with time, making it suitable for estimating when meteoric water seeped into the ground.

In a recent study published in the journal Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, USGS scientists measured variations in oxygen and hydrogen isotope ratios and tritium concentrations in meteoric water, as well as in hot water discharged in Yellowstone’s geyser basins. The results provided several new insights into how water flows beneath the surface in Yellowstone, including:

- Hot springs are fed by water that is recharged throughout the volcanic plateau, mostly through fractured, permeable tuff (compacted ash) units. Most of these units, mainly the Lava Creek Tuff (which was erupted during the formation of Yellowstone caldera about 631,000 years ago) are located around the margins of Yellowstone caldera.

- Groundwater that discharges through hot springs in the central parts of the Upper and Lower Geyser Basins flows in deeper and older rhyolite units that have higher temperatures compared with groundwater flowing in shallower and younger rhyolite units that discharge from springs on the margins of the basins.

- The relative abundance of hydrogen and oxygen isotopes in water from the rain and snow that seep into the ground changes significantly between years and even within a single year. In contrast, hydrogen and oxygen isotopes in hot spring barely vary with time. This means that the volume of groundwater beneath Yellowstone caldera and the surroundings is substantially larger than the volume of water seeping into the ground each year.

- Hot springs in the central part of the geyser basins mostly contain water that was recharged into the subsurface before the development and testing of thermonuclear weapons in the 1950s and 60s, when tritium concentrations in the atmosphere were significantly higher. In comparison, waters discharged from hot springs at the margins of the basins contain measurable amounts of tritium, indicating that some of the water has seeped into the ground since the 1950s. For example, tritium concentrations in water erupted from Old Faithful Geyser in the central part of the Upper Geyser Basin are too low for modern instruments to measure. In contrast, some of the springs on the margins of the Upper Geyser Basin have almost half of the tritium concentration measured in present-day rainfall. This contrast in tritium concentrations suggests short and relatively fast groundwater flow to springs on the basin’s margins and longer and/or slower flow to the springs in the central part of the basins.

Although the water in Yellowstone’s hot springs all looks the same, small differences in the composition of water molecules hide important secrets about Yellowstone’s hydrothermal system. By unlocking some of these secrets, the new study revealed that there is a huge volume of water beneath the ground, that water flow towards the geysers in the center of the basins is deeper and occurs over longer time periods compared with flow to springs on the margins of the basins, and that it takes at least many decades to centuries for the water in snowmelt or a rain to end up erupting from features like Old Faithful Geyser. That’s a lot of valuable information from one little water molecule!