Solving the Mystery of Sea Star Wasting Disease: A Breakthrough Discovery

The bacteria causing one of the largest marine species die-offs ever recorded was recently discovered at USGS Western Fisheries Research Center’s, Marrowstone Marine Field Station!

If you’ve spent time tide pooling along the West Coast lately, you may have noticed something troubling: sea stars with twisted arms, lesions, or bodies that seem to be melting away. This distressing sight is a trademark of Sea Star Wasting Disease (SSWD), a sickness that has devastated sea star populations along the Pacific Coast of North America since mass die-offs occurred in 2013. Now, for the first time, scientists, including those at the USGS Western Fisheries Research Center (WFRC), have solved a decades-long mystery and identified the cause of this devastating disease.

In 2013, SSWD emerged along the Pacific Coast as one of the largest marine epidemics ever recorded. Sea stars, which play an important role in marine ecosystems, began exhibiting symptoms such as white lesions, decaying tissue, and a general weakening of the body. Over the course of just a few days, stars then appeared to “melt” as their limbs twisted and broke off, killing and laying waste to entire populations. This catastrophic loss affected at least 20 species of sea stars, including some of the most iconic, like the sunflower sea star.

The cause of the disease has eluded scientists for years. Researchers speculated that the cause may have been a viral infection, or that there was a link between the disease, higher ocean temperatures, and heat waves. The mystery remained unsolved—until now.

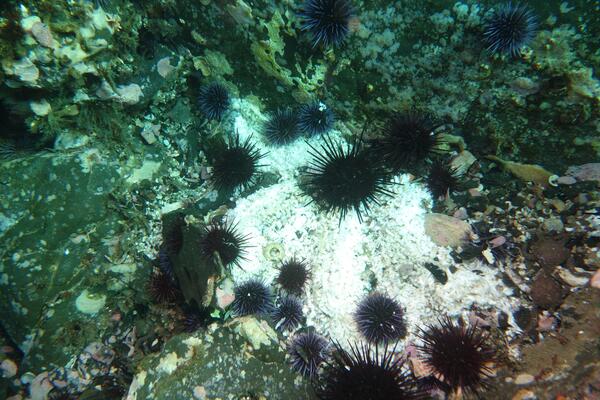

Sunflower sea stars can grow up to the size of a car tire! They consume lots of sea urchins, preventing urchins from over-consuming kelp and upsetting entire kelp forest ecosystems.

A Groundbreaking Discovery

In a major breakthrough, scientists from multiple entities, led by the Hakai Institute and the University of British Columbia converged at WFRC’s Marrowstone Marine Field Station and pinpointed the cause of SSWD: a strain of the bacterium Vibrio pectenicida. This discovery, published in Nature Ecology & Evolution, will provide crucial insight into future management of marine disease outbreaks.

The researchers used sunflower sea stars (Pycnopodia helianthoides) for their experiments a species that plays a critical role in marine ecosystems and is particularly susceptible to SSWD. Using Pycnopodia allowed scientists to pinpoint the disease’s cause and to address the broader ecological consequences tied to the sea star’s decline.

To identify the cause of SSWD, scientists first collected infected sea stars from the wild and took samples of their coelomic fluid (essentially the "blood" of sea stars). They then analyzed genetic material from a sample to identify the microorganisms present. This approach revealed a V. pectenicida in a high proportion of the infected sea stars compared to healthy ones. By successfully recreating the disease in the lab, the team confirmed that the bacterium was indeed the cause of Sea Star Wasting Disease.

WFRC’s Marrowstone Marine Field Station, located along the shores of Puget Sound, is uniquely equipped to study marine diseases. The station’s access to seawater, isolated tanks, controlled temperatures, water treatment and other biosecurity measures make it one of the very few places this study could be safely performed. WFRC science and support staff have decades of expertise studying aquatic disease making them crucial to the success of this project.

A sea star dying from Sea Star Wasting Disease.

Looking Forward: A Step Toward Recovery

Now that the pathogen behind SSWD has been identified, scientists are turning their attention to understanding the factors that drive disease outbreaks related to Vibrio and the resilience of marine species.

Scientists are working to understanding how sea stars respond to Vibrio pectenicida in varying environmental conditions . Also, a broader analysis of Vibrio species will occur. Vibrio species commonly lead to disease in marine organisms, and decades of evolution host-pathogen relationships may teach us something about how resilience is formed that can be translated to sea stars. For example, Vibrio parahaemolyticus is commonly found in oysters and linked to acute food poisoning. V. anguillarum and V. ordalii cause disease and mortality in salmon throughout the Pacific Northwest. V. cholerae produces a collection of symptoms under its eponymous name cholera. Finally, other strains of V. pectenicida, the cause of SSWD, also disease cultivated scallops.

This great science and other work to unravel the complexities of aquatic diseases offers hope for the health of our marine and freshwater ecosystems.