Idaho’s forgotten eruptions—the Challis volcanics

Although the Yellowstone hotspot burned a swath of volcanic chaos across southern Idaho during the past 17 million years, it was an earlier period of volcanism, unrelated to Yellowstone, that shaped the geology of central Idaho.

Yellowstone Caldera Chronicles is a weekly column written by scientists and collaborators of the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory. This week's contribution is from Zach Lifton, geologist with the Idaho Geological Survey.

If you’ve spent any time in central Idaho, you may have heard the term “Challis volcanics.” The name describes a large volume of Eocene (a geologic epoch that lasted from 56 to 34 million years ago) volcanic rocks, formally called the Challis Volcanic Group, but is also used more generally to refer to the magmatic event that produced them and the time period it occurred. What are these rocks, and why are they there?

Idaho hosts a diverse range of volcanic rocks, from 200-million-year-old basalts scraped off the ocean floor during ancient subduction to “fresh” 2,000-year-old lava flows at Craters of the Moon. While Yellowstone is a major player in the volcanic history of the area, an earlier unrelated episode of magmatism also had a big impact on the region.

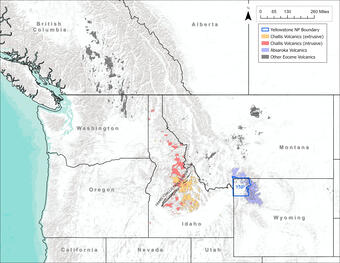

Challis volcanism occurred about 52–45 million years ago in central Idaho. It was part of a larger flare up of magmatism at the same time in British Columbia, Washington, Montana, and Wyoming. This shows up as a broad swath of Eocene volcanic rocks called the Challis-Kamloops Belt. The Absaroka volcanic field east of Yellowstone is a well-known part of this volcanic flare up. Although typically associated with central Idaho, Challis volcanic rocks are found widely across Idaho—as far north as Lake Pend Oreille, as far south as the Owyhee Mountains, and as far east as Henrys Lake.

The Challis volcanic event deposited a huge volume of material, covering an area of approximately 10,000 square miles (25,000 square kilometers). The resulting rocks are chemically and texturally diverse. They include extrusive rocks like rhyolite, dacite, and andesite that erupted at the surface in lava flows, domes, and explosive ash-forming eruptions. They also include intrusive rocks such as granite, diorite, and granodiorite that rose through the crust as dikes and plutons but remained underground. Lava flows erupted from distributed vents and fissures, forming stratovolcanoes. Explosive eruptions produced ash-flows and resulted in the formation of several collapse calderas.

Much of the Challis volcanism occurred along or near a long series of southwest-northeast normal faults called the Trans-Challis fault system. Extension along these faults probably guided the emplacement of Challis intrusive rocks. This relation has important economic implications. The Challis volcanics and Trans-Challis fault system correlate in space and time with gold, silver, and molybdenum deposits that formed from hot, mineral-rich waters in central Idaho.

What caused this dramatic, widespread, and relatively short-lived episode of volcanic activity? The entire Challis-Kamloops Belt, including the Challis volcanics, is related to steepening of the subducting Farallon plate. Prior to the Challis volcanics event the oceanic Farallon plate had been subducting at a shallow angle underneath the North American plate for tens of millions of years, resulting in volcanoes closer to the coastline. At some point, part of the subducted slab seems to have broken off, and the detached slab tilted down steeply. The steepening of the slab allowed hot mantle material to well up under the crust along the Challis-Kamloops Belt. That upwelling caused melting due to decompression, and widespread volcanism was the result.

So, while the Yellowstone hotspot has been the driving force for volcanism for the last 17 million years, the volcanic story in western North America is much older and more diverse. The Challis volcanics are a great example of how continental-scale dynamics have both regional and local impacts.