Remembering the Gros Ventre Slide of 1925

One hundred years ago, on June 23, 1925, a mountainside in the Gros Ventre Range in northwest Wyoming collapsed, unleashing one of the largest landslides in North America‘s recorded history. A century later, we can reflect on that day’s events.

Yellowstone Caldera Chronicles is a weekly column written by scientists and collaborators of the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory. This week's contribution is from James Mauch, geologist with the Wyoming State Geological Survey.

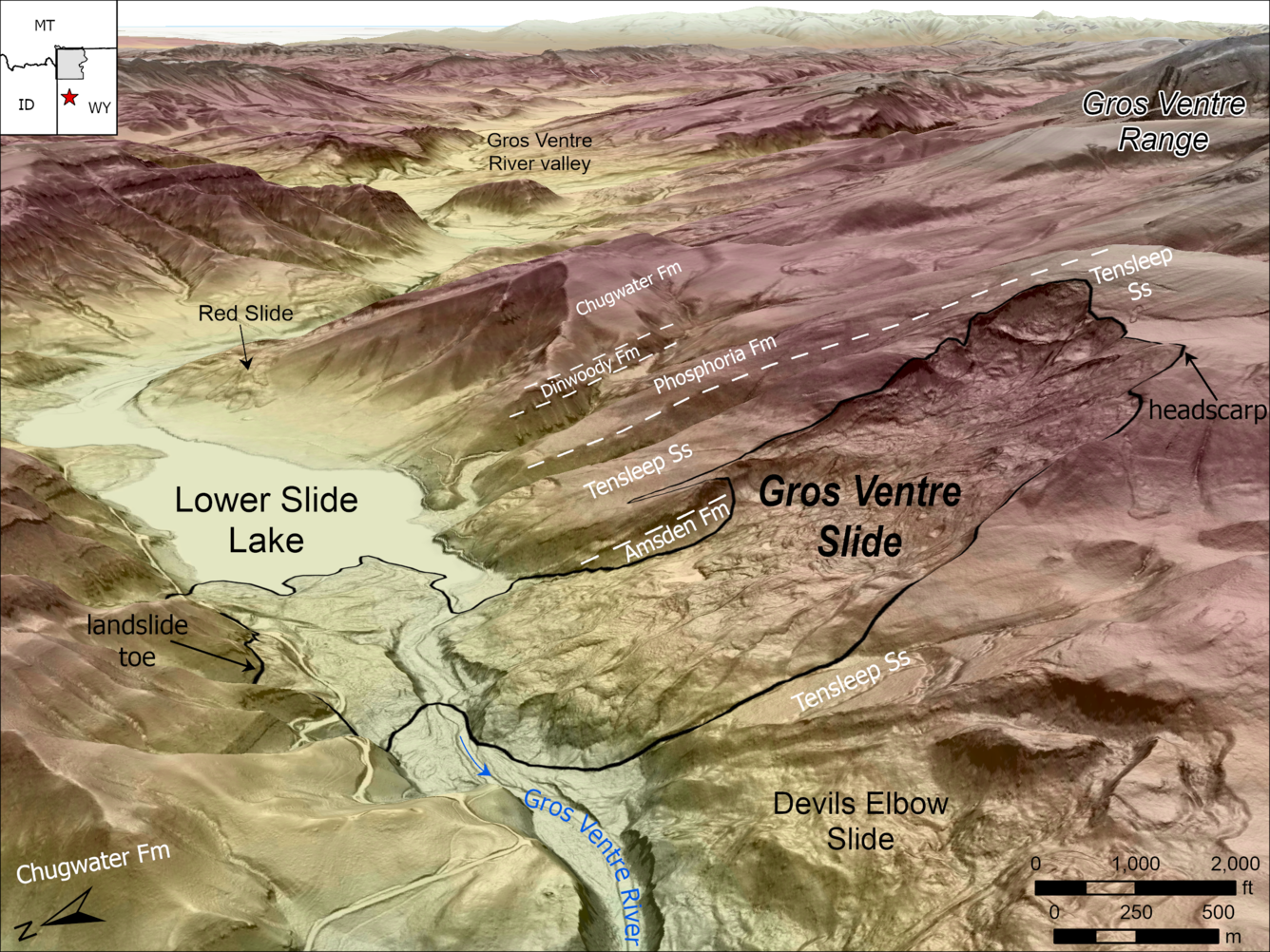

June 23, 2025, marks the 100th anniversary of the Gros Ventre Slide, the largest and one of the most impactful landslides to occur in the Greater Yellowstone region in recorded history. At approximately 4 PM on that day in 1925, an estimated 50 million cubic yards (38 million cubic meters) of rock and debris tumbled down the north side of Sheep Mountain—14 miles (23 kilometers) northeast of the town of Jackson, Wyoming—and into the valley of the Gros Ventre River 2,100 feet (640 meters) below. Within minutes the valley floor was buried beneath more than 200 feet (61 meters) of rocky debris and the river was dammed, creating Lower Slide Lake.

Remarkably, the 1925 landslide claimed no lives. Rancher Guil Huff, whose firsthand account remains invaluable to geologists studying the event, narrowly escaped the surging debris with his horse at a full gallop. However, tragedy struck about two years later on May 18, 1927, when the snowmelt-swollen Gros Ventre River breached the landslide dam and unleashed a devastating flood. This flood destroyed the town of Kelly, 4 miles (6 kilometers) downstream from the dam, and resulted in six fatalities. The lessons learned from the Kelly Flood would prove crucial in the aftermath of the 1959 Madison Slide, a consequence of the M7.3 Hebgen Lake earthquake, when engineers averted a similar disaster by constructing a spillway to lower the water level in the lake that formed on the Madison River upstream of the slide.

What caused the Gros Ventre Slide? The south side of the Gros Ventre River valley, where the landslide occurred, is underlain by sedimentary rocks that are tilted northward roughly parallel to the forested hillslope. The base of this hillslope is undercut as a result of the long-term incision and erosion by the river. The rock exposed at the surface of the slope is the Tensleep Sandstone—a layer that groundwater can easily penetrate due to the space between sand grains as well as numerous joints and fractures. Beneath the Tensleep Sandstone, the shale beds of the Amsden Formation form a barrier to groundwater flow. This allows for groundwater to collect at the interface between the Tensleep and Amsden, where weak, heavily weathered siltstone layers are present.

When these weak layers become saturated with water, they lose their frictional strength and become more likely to fail. This was the exact condition that preceded the Gros Ventre Slide in the spring of 1925, which was marked by unusually warm and wet weather that saturated the ground. The final landslide trigger may have been an earthquake. Although there were no seismic instruments in the area at the time, local residents reported feeling several earthquakes in the weeks leading up to June 23—including an earthquake of estimated magnitude 3–4 that occurred at 8 PM on June 22, just 20 hours before the landslide. It’s possible that ground shaking from this earthquake kicked off a chain reaction that began with liquefaction of the saturated, weak layers at the base of the Tensleep and culminated hours later with massive collapse of the hillside. The result was a profound change to the landscape that is unmistakable to this day.

While much has changed in the century since the Gros Ventre Slide, the underlying geologic factors that contributed to the event remain the same. The Gros Ventre River valley, like many of the mountainous areas surrounding Yellowstone, is characterized by steep slopes and relatively weak rocks, making landslides an ongoing risk. Thanks to modern tools like lidar and landslide susceptibility mapping, we have a better sense than ever before where landslides have occurred in the past and where they will likely occur in the future. The legacy of such historic events underpins the work of Yellowstone Volcano Observatory scientists who study geologic hazards and communicate their findings with the public. One hundred years later, the Gros Ventre Slide stands as an important milestone in the human and natural history of the Greater Yellowstone region, reminding us of the power and destructive potential of unstable slopes in this dynamic landscape.

Further reading

Alden, W.C., 1928, Landslide and flood at Gros Ventre, Wyoming: Transactions of the American Institute of Mining and Metallurgical Engineers, v. 76, p. 347–360.

Smith, R.B., Pelton, J.R., and Love, J.D., 1976, Seismicity and the possibility of earthquake related landslides in the Teton-Gros Ventre-Jackson Hole area, Wyoming: Contributions to Geology, University of Wyoming, v. 14, no. 2, p. 57–64, https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/uwyo/rmg/article-abstract/14/2/57/87702/Seismicity-and-the-possibility-of-earthquake?redirectedFrom=PDF.

Voight, Barry, 1978, Lower Gros Ventre Slide, Wyoming, U.S.A., in Voight, Barry, ed., Rockslides and Avalanches, 1—Natural Phenomena, Developments in Geotechnical Engineering, v. 14A: Amsterdam, Elsevier, p. 113–162, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-41507-3.50011-8.