The term “legacy data” refers to project data that are complete, or may be resurrected in the future, that were previously stored in old or obsolete formats and thus, difficult to access. These data are an important record of past ecosystem status and part of the USGS commitment to deliver actionable information relevant to decision makers. Here, we discuss these data with the Alaska Science Center Data Management Team.

Return to USGS Alaska Q&A Series

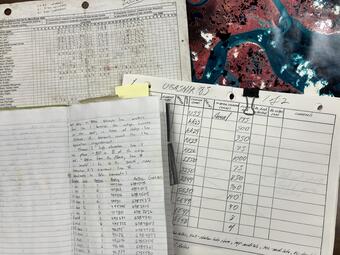

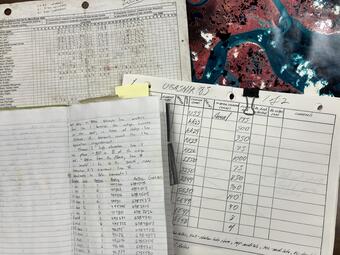

We’ve all heard those stories of someone finding a box of old notebooks or photographs in an attic, long forgotten, but that then come to be highly insightful for quantifying the amount of change that has happened over time or for confirming an assumption about past conditions.

The USGS Alaska Science Center has been cleaning out our attic lately to ensure that legacy data and images are archived and made available to the public. The scientific results from these projects, which took place across Alaska, were published decades ago but often without easy access to the data, notes, and images from those projects. The Alaska Science Center is now ensuring that those legacy data are well archived and publicly available.

In this Q&A, we talk with members of the USGS Alaska Science Center Data Management Team, Laura McDuffie, Marla Hood, and John Reed about organizing, archiving, and releasing legacy data. This team has led in the development of data management and archival standards for the USGS Alaska Science Center and others.

Q: What’s different about legacy data compared to regular data that USGS releases?

Laura: Most “modern” data releases consist of tabular or GIS data that were either collected electronically in the field or transcribed into an electronic format after returning from the field. What makes legacy data different is that the physical, hard-copy datasheets, notebooks, photos, and maps, have never been transcribed into a computer-readable format. The process of digitizing legacy data involves scanning all relevant data and producing PDF formatted documents that are then saved within our internal archive.

Instead of the public being able to download all that PDF formatted data, with legacy data releases, the public can view a concise metadata record and inventory list of all data that has been digitized and archived by the Alaska Science Center. This inventory allows public users to see which data products are available and request access. This process not only reduces the amount of data that must be stored online, but also resolves some of the accessibility issues with most legacy data.

Marla: With any documents posted online, the federal government is required to make sure they are compliant with Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. This means any technical information posted needs to be accessible to those with disabilities. Legacy data is often not easily converted to fully accessible formats, but we still want to be sure the public is aware of its existence. For example, see this website that lists archived data collected from 1974 to 1992 on the Arctic Coastal Plain of Alaska.

John: Often, we cannot fully document legacy data as we do with new data. Missing methods, imprecise locations, penmanship, and smudges are among the many challenges. Though less than ideal, the data are still valuable. We try to indicate deficiencies and provide links to related reports and articles which can help determine appropriate uses of the data. As we go through boxes of legacy data, we have also found many old unpublished reports. We send those to the Alaska Resources Library and Information Services (ARLIS) where they are archived and accessible to the public.

Q: Have any of the USGS legacy data been used to compare to more recent information?

John: In the 1990s researchers from the Alaska Science Center, studying the decline of spectacled eiders in western Alaska, measured lead exposure as a possible cause. In a recent USGS publication, legacy demographic and blood lead data were compared to data collected in 2022. Lead exposure was similar across that time span, while the number of nests increased. Another example is the use of sites at Izembek Lagoon that were sampled for benthic invertebrates by USGS in 1998. These sites have been resampled to quantify changes in benthic invertebrates, which may have led to changes in the distribution of Steller’s eiders – which feed on these invertebrates – in the lagoon. These results demonstrate the importance of historical datasets to the understanding of complex environmental interactions and contemporary conditions.

Q: Have you found any surprises in the legacy data you’ve been working with?

Laura: Many of the projects the Alaska Science Center Data Management Team has been archiving are related to bird biology. Within the various notebooks, we have come across bird species checklists which indicate which species, and how many of each, were present at a specific location and on a specific date. Many of these checklists have now been transcribed into an electronic format and imported into eBird, an online database where citizen scientists and ornithologists alike can submit data on bird abundance. Data from eBird provides information on bird distributions and population trends. To date, the Alaska Science Center has submitted 9,943 checklists, with over half of those submitted for dates prior to the eBird database establishment in 2002.

Q: Organizing and archiving boxes of legacy data sounds time consuming. How do you stay motivated?

Laura: Personally, it feels good to archive and then share data that has not been previously secured and made publicly available. Many of these legacy datasets were collected long before the USGS Alaska Science Center was established and several of the project leaders for these legacy datasets have since retired. Additionally, I enjoy looking through old photographs during the archival process and reliving the field experiences from 10, 20, or even 30 years ago.

Marla: I appreciate that we’re making a concerted effort to not leave future staff to deal with this data. We’ll never know what may help answer questions in the future, but these data were collected on important natural resource topics in the past, so they need to be preserved. I currently work with several more modern databases at our Center and so I like to think about where legacy data could be valuable additions to any of those.

Legacy Research Data from Retired, Emeritus, and Current USGS Alaska Science Center Staff

The term “legacy data” refers to project data that are complete, or may be resurrected in the future, that were previously stored in old or obsolete formats and thus, difficult to access. These data are an important record of past ecosystem status and part of the USGS commitment to deliver actionable information relevant to decision makers. Here, we discuss these data with the Alaska Science Center Data Management Team.

Return to USGS Alaska Q&A Series

We’ve all heard those stories of someone finding a box of old notebooks or photographs in an attic, long forgotten, but that then come to be highly insightful for quantifying the amount of change that has happened over time or for confirming an assumption about past conditions.

The USGS Alaska Science Center has been cleaning out our attic lately to ensure that legacy data and images are archived and made available to the public. The scientific results from these projects, which took place across Alaska, were published decades ago but often without easy access to the data, notes, and images from those projects. The Alaska Science Center is now ensuring that those legacy data are well archived and publicly available.

In this Q&A, we talk with members of the USGS Alaska Science Center Data Management Team, Laura McDuffie, Marla Hood, and John Reed about organizing, archiving, and releasing legacy data. This team has led in the development of data management and archival standards for the USGS Alaska Science Center and others.

Q: What’s different about legacy data compared to regular data that USGS releases?

Laura: Most “modern” data releases consist of tabular or GIS data that were either collected electronically in the field or transcribed into an electronic format after returning from the field. What makes legacy data different is that the physical, hard-copy datasheets, notebooks, photos, and maps, have never been transcribed into a computer-readable format. The process of digitizing legacy data involves scanning all relevant data and producing PDF formatted documents that are then saved within our internal archive.

Instead of the public being able to download all that PDF formatted data, with legacy data releases, the public can view a concise metadata record and inventory list of all data that has been digitized and archived by the Alaska Science Center. This inventory allows public users to see which data products are available and request access. This process not only reduces the amount of data that must be stored online, but also resolves some of the accessibility issues with most legacy data.

Marla: With any documents posted online, the federal government is required to make sure they are compliant with Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. This means any technical information posted needs to be accessible to those with disabilities. Legacy data is often not easily converted to fully accessible formats, but we still want to be sure the public is aware of its existence. For example, see this website that lists archived data collected from 1974 to 1992 on the Arctic Coastal Plain of Alaska.

John: Often, we cannot fully document legacy data as we do with new data. Missing methods, imprecise locations, penmanship, and smudges are among the many challenges. Though less than ideal, the data are still valuable. We try to indicate deficiencies and provide links to related reports and articles which can help determine appropriate uses of the data. As we go through boxes of legacy data, we have also found many old unpublished reports. We send those to the Alaska Resources Library and Information Services (ARLIS) where they are archived and accessible to the public.

Q: Have any of the USGS legacy data been used to compare to more recent information?

John: In the 1990s researchers from the Alaska Science Center, studying the decline of spectacled eiders in western Alaska, measured lead exposure as a possible cause. In a recent USGS publication, legacy demographic and blood lead data were compared to data collected in 2022. Lead exposure was similar across that time span, while the number of nests increased. Another example is the use of sites at Izembek Lagoon that were sampled for benthic invertebrates by USGS in 1998. These sites have been resampled to quantify changes in benthic invertebrates, which may have led to changes in the distribution of Steller’s eiders – which feed on these invertebrates – in the lagoon. These results demonstrate the importance of historical datasets to the understanding of complex environmental interactions and contemporary conditions.

Q: Have you found any surprises in the legacy data you’ve been working with?

Laura: Many of the projects the Alaska Science Center Data Management Team has been archiving are related to bird biology. Within the various notebooks, we have come across bird species checklists which indicate which species, and how many of each, were present at a specific location and on a specific date. Many of these checklists have now been transcribed into an electronic format and imported into eBird, an online database where citizen scientists and ornithologists alike can submit data on bird abundance. Data from eBird provides information on bird distributions and population trends. To date, the Alaska Science Center has submitted 9,943 checklists, with over half of those submitted for dates prior to the eBird database establishment in 2002.

Q: Organizing and archiving boxes of legacy data sounds time consuming. How do you stay motivated?

Laura: Personally, it feels good to archive and then share data that has not been previously secured and made publicly available. Many of these legacy datasets were collected long before the USGS Alaska Science Center was established and several of the project leaders for these legacy datasets have since retired. Additionally, I enjoy looking through old photographs during the archival process and reliving the field experiences from 10, 20, or even 30 years ago.

Marla: I appreciate that we’re making a concerted effort to not leave future staff to deal with this data. We’ll never know what may help answer questions in the future, but these data were collected on important natural resource topics in the past, so they need to be preserved. I currently work with several more modern databases at our Center and so I like to think about where legacy data could be valuable additions to any of those.