A Hidden Risk Below the Surface: Monitoring Gas Bubble Trauma in the Columbia River Basin

WFRC scientists are helping protect fish health in the shadow of the West’s largest hydropower dams.

For decades, scientists at the USGS Western Fisheries Research Center (WFRC) have worked alongside dam operators to monitor a lesser-known threat to fish in the Columbia and Snake rivers: gas bubble trauma. This work has helped managers balance power production with the needs of migrating fish. Today, researchers at WFRC’s Columbia River Research Laboratory are expanding their efforts to include more species and more locations—bringing this critical science to new reaches of the river.

Why Gas Bubble Trauma Matters

To understand gas bubble trauma, imagine scuba divers surfacing too quickly. As pressure decreases, dissolved gases in their blood can form bubbles, causing joint pain, paralysis, and even death—a condition commonly known as “the bends.” Fish can experience something similar.

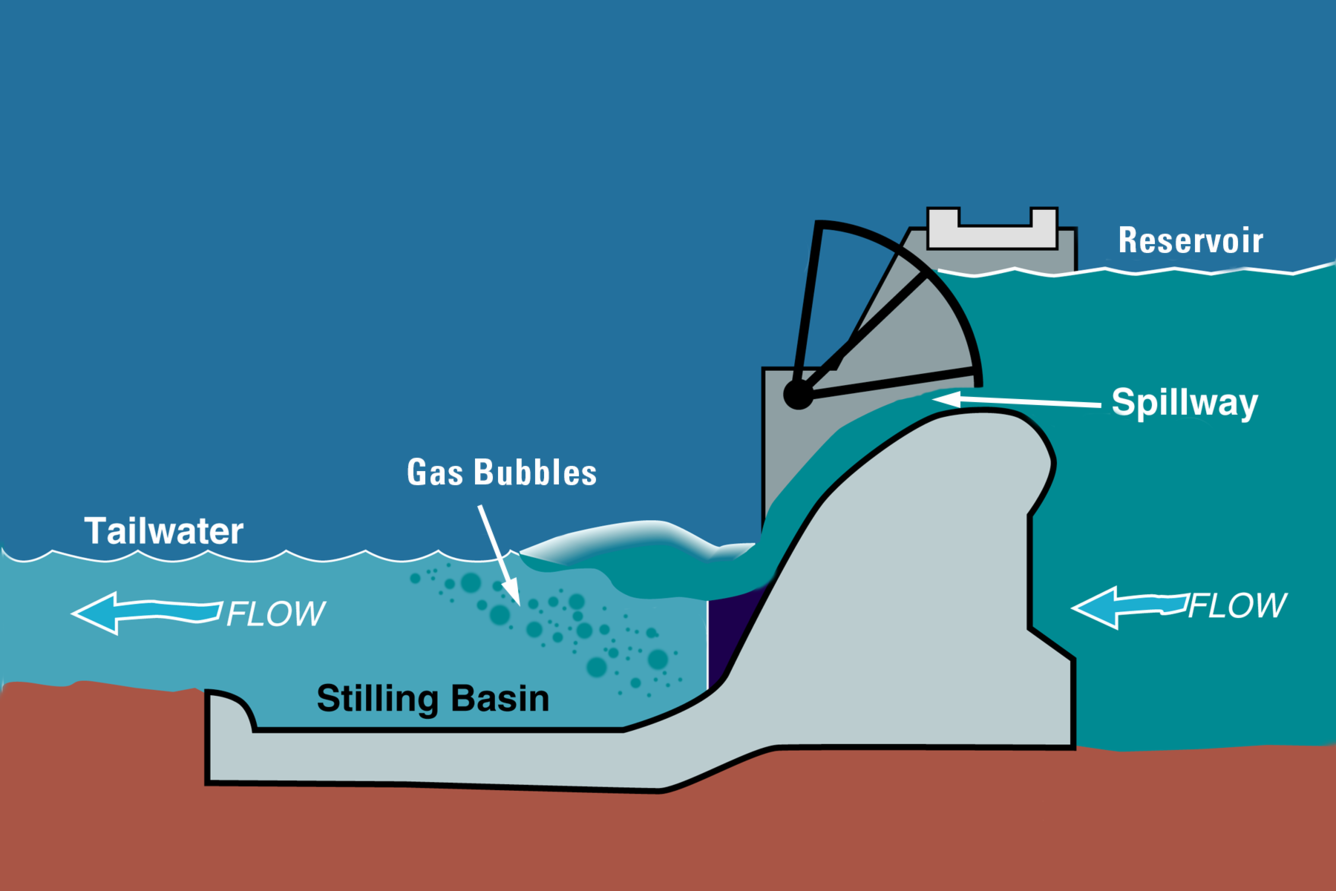

At large dams like those in the Columbia River Basin, managers often release water over spillways. The more water released at the top of the dam, the more air becomes trapped in the high flows. The trapped air then plunges deep into the water at the base of the dam, under pressure—creating super-saturated gas conditions. As fish rise toward the surface, pressures decrease, gas comes out of solution in their bodies, and bubbles form in tissues and organs. The result is gas bubble trauma, or GBT—a condition that can cause fin and eye damage, hemorrhaging, disorientation, and sometimes death.

GBT is largely an unintended consequence of efforts to help our region’s salmon. While increasing spill helps young salmon migrate more safely downriver and to the ocean, it also raises dissolved gas levels in the water. This makes real-time monitoring essential, allowing managers to fine-tune dam operations to balance protecting salmon transiting the dams, providing safe habitat for all fish below the dams, and continuing to deliver hydropower and manage water storage.

Supporting Smarter Spill Management

Since the early 1990s, WFRC has supported state and federal agencies by providing regular assessments of gas bubble trauma in salmon at the Bonneville Dam and the Lower Snake River dams. But salmon aren’t the only fish affected. In 2020, scientists at the Cook lab began monitoring GBT in resident species like sculpin, northern pikeminnow, and three-spined stickleback. These fish offer year-round insights into river conditions and help fill gaps in areas where salmon may not be present.

Each week during spill season, researchers collect fish near dams and bring them to the WFRC facility in Cook, Washington. There, scientists examine the animals under a microscope and score symptoms of GBT using a standardized scale. This information is reported to the Washington Department of Ecology and the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality—two agencies that set legal limits for gas saturation in the river—and is used to help guide dam operations.

Expanding Science Upstream

In 2024, WFRC expanded this monitoring to the Grand Coulee and Chief Joseph dams—the two largest hydropower projects in the Columbia Basin. Located farther upstream, these dams affect critical habitat for resident fish species, including white sturgeon and native trout. By expanding GBT assessments to these sites, WFRC is helping extend fish protection efforts beyond salmon and into the upper reaches of the watershed.

This work matters for more than just fish. Dams in the Columbia Basin produce roughly 20% of the electricity used in the western United States. They provide low-emission power to homes and industries and help regulate water for agriculture, navigation, and flood control. Managing spill for fish is one part of a much larger balancing act—and GBT monitoring helps ensure that those tradeoffs are informed by the best available science.

A Crucial Piece of the Puzzle

Gas bubble trauma doesn’t attract the same attention as fish ladders or turbine upgrades. It’s invisible to the casual observer—tiny bubbles beneath the surface, symptoms often seen only under a microscope. But for fish, GBT can be life-threatening. And for dam operators, it’s a critical piece of information that influences how water is managed day to day.

The USGS Western Fisheries Research Center plays a unique role in this work. With decades of experience in aquatic animal health, long-term partnerships across the region, and specialized facilities like the Cook field station on the Columbia River, WFRC brings continuity, technical rigor, and scientific independence to an issue that links energy, ecology, food security, and water management.