Pathology Case of the Month - Great-Horned Owl and Eurasian Collared-Dove

Case History: An adult female Great-Horned Owl (Bobo virginianus) was found dead in a residential yard in Utah, U.S. with an immature male Eurasian Collared-Dove (Streptopelia decaocto) clutched in its left foot.

Gross Findings: The owl was in good body condition with abundant fat stores. There was mild singeing of the tips of the rictal bristles on the right side of the face (Fig. 1A). The right eyelid was moderately thickened, and the right cornea was moderately cloudy and thickened (Fig. 1A). On the plantar aspect of the left foot were multiple ulcerations up to 2 x 3 mm with thickened yellow edges (Fig. 1B). There was red streaking on the medial and lateral digits of the right foot (Fig. 1C). A focal 5 x 2-mm rupture was present in the right atrium of the heart (Fig. 1D). The stomach contained abundant fur and rodent bones. There were no other significant findings.

The dove was in good body condition. There was a penetrating wound through the dorsum into the coelomic cavity; the left lung, left liver lobe, and proventriculus were absent (predatory trauma). At the base of the tail was a 3 x 1.4-cm wound with blackened edges (Fig. 1E). Within the left pectoral muscle was a 1-cm diameter pale tan area overlain by tan crusty material with an adjacent 5-mm diameter focal dark red area. The heart was covered by a large blood clot which partially extended through a 2-mm diameter right atrial defect (Fig. 1F). The crop contained abundant corn and mixed seeds. There were no other significant findings.

Histopathological Findings:

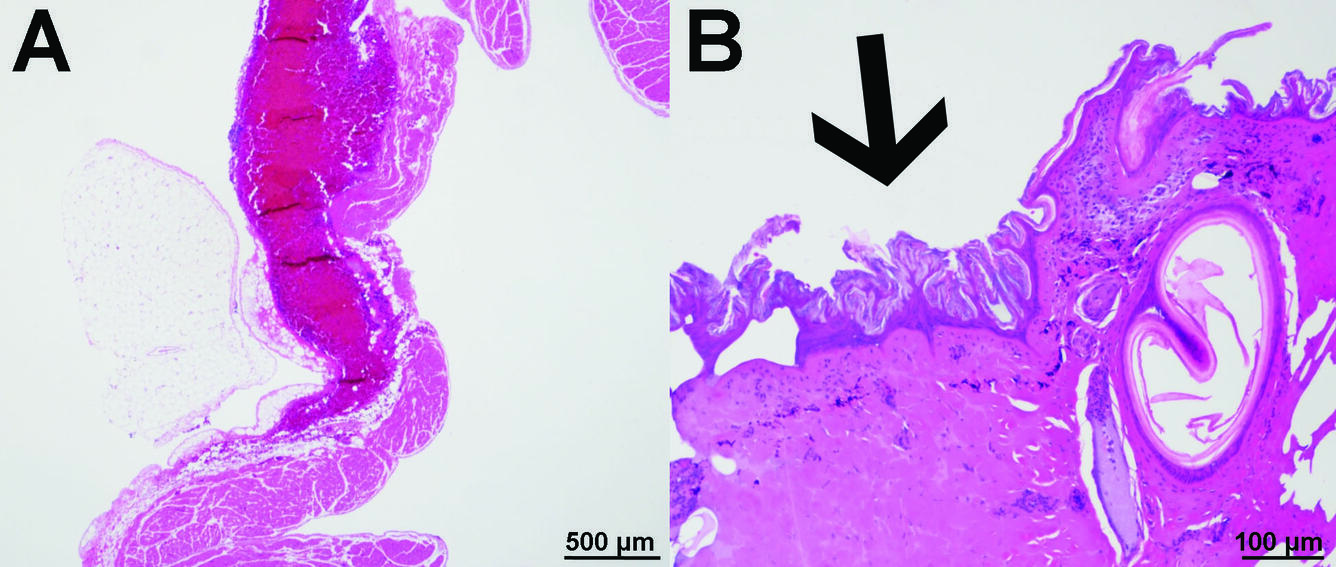

Great-Horned Owl: There is multifocal acute right atrial hemorrhage (Fig. 2A) and multifocal acute marked epidermal and dermal coagulative necrosis (Fig. 2B). There was moderate peracute pulmonary hemorrhage.

Eurasian Collared-Dove: There was focal acute hemorrhage adjacent to a great vessel at the base of the heart. Within the pectoral muscle was regionally extensive acute segmental myonecrosis. There was multifocal marked pulmonary hemorrhage.

Morphologic Diagnoses:

Great-Horned Owl

- Heart, right atrium: Hemorrhage, multifocal, acute, moderate

- Skin: Burns, multifocal, acute, marked

- Lungs: Hemorrhage, multifocal, cute, moderate

Eurasian Collared-Dove

- Heart, right atrium: hemorrhage, multifocal, mild to moderate, acute

- Pectoral muscle: Segmental necrosis, regionally extensive, acute, moderate

- Lung: Hemorrhage, multifocal, acute, marked

Condition: Electrocution

Etiology: Moderate voltage powerlines (2.4 to 60 kilovolts) are most commonly associated with electrocution of raptors. High voltage lines (currents greater than 600 V) are less often implicated.

Predisposing risk factors: Body size, habitat, young age, power line configuration

Distribution: Worldwide

Seasonality: Any time of year, but more frequent with rain, snow, or windy conditions that increase the conductivity of feathers and make the birds less stable while landing, taking off, or in flight

Host range: Large avian species such as eagles, hawks, and owls, due to their broad wingspan and preference for exposed perching sites. Immature and subadult raptors may be at increased risk due to inexperience or higher risk perch selection preferences.

Field: Location is not definitive, but electrocuted birds are typically found dead near a utility pole or beneath a power line with or without bird-friendly modifications. There may be evidence of an associated vegetation fire and/or history of a local electrical power outage.

Clinical signs: Electrocuted birds are often found dead but may survive the initial injury and recover or die later from complications. Clinical signs include blackened and curled (singed) feathers, open wounds, especially on the feet, and limb fractures or amputations.

Mechanism of injury: Birds are electrocuted when they make contact with two pieces of live electrical equipment or an electrical element and a grounded object.

Pathogenesis and pathology: When a bird completes an electrical circuit, damage is sustained over the path through which the electric current enters and leaves the body. Injury is due both to thermal damage and electroporation (formation of pores in cellular membranes). Death results from damage to the cardiac and/or respiratory centers of the brain or direct injury to the heart.

Diagnosis:

- Evidence of charring or burns of the skin or feathers at the site of contact with the electrical source, most often on the ventral aspects of the wings distal to the elbows and the lower legs or feet. Burns can be small and obscured beneath feathers or mistaken for dirt or blood staining. Burned feathers, including rictal bristles, can have twisted or curled edges. In owls, rictal bristles may be the only visibly burned feathers. The scales of the feet and legs may have dry blisters or areas with red to gray discoloration.

- Rupture of the right atrium of the heart is common, resulting in hemopericardium or hemocoelom. Findings consistent with blunt force trauma, such as liver fracture, may also be present due to a fall to the ground after electrocution. Bilateral cataracts have been reported from one case of a great-horned owl.

- Histopathological lesions of the skin are characterized by subepidermal separation, epidermal and dermal coagulative necrosis, epidermal nuclear elongation, dermal (collagen) homogenization, and dark staining of the nuclei of the cells of epidermal layer.

- Examination with an alternate light source (530 - 570 nm with red filter) may help to distinguish burns from dirt or blood staining. Burned skin, feathers, and beak will exhibit red photoluminescence.

- Wet mounts of burned feathers may reveal broken barbs or vanes with melting or charring at the ends, while burned skin may have tan to gray discoloration and melting of the papillae.

Wildlife population impacts: Powerlines are a significant cause of death, fatally electrocuting approximately 0.9 to 11.6 million birds each year.

Management: Electrical poles: According to the Avian Powerline Interaction Committee, a minimum horizontal and vertical separation of 60 inches and 40 inches, respectively, should be maintained between energized and grounded elements (see https://www.aplic.org/).

References:

Harness RE, Wilson KR. 2001. Electric-utility structures associated with raptor electrocutions in rural areas. Wildl Soc Bull 29:612–623.

Kagan RA. 2016. Electrocution of raptors on power lines: A review of necropsy methods and findings. Vet Pathol 53:1030–1036.

Lehmana RN, Kennedy PL, Savidgec JA. 2007. The state of the art in raptor electrocution research: A global review. Biol Conserv 136:159-174.

Viner TC, Kagan RN. 2018. Chapter 2 - Forensic Wildlife Pathology. In: Pathology of Wildlife and Zoo Animals, Terio KA, McAloose D, St. Leger J, editors. Elsevier, Inc., Amsterdam, Netherlands, pp. 21–40.

Thomas NJ. 1999. Chapter 50 - Electrocution. In: Field Manual of Wildlife Diseases: General Field Procedures and Diseases of Birds, Friend M, Franson JC, editors. U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, pp. 357–360. Available online: https://pubs.usgs.gov/itr/1999/field_manual_of_wildlife_diseases.pdf. Accessed 29 November 2019.