Earthquake swarms in California: What’s the difference between magmatic and tectonic?

If you live in California, you've almost certainly felt an earthquake - maybe more than one. Maybe, as the residents of the Bay Area city of San Ramon are finding out, you get to feel a LOT of earthquakes. But how can we tell what's causing them?

The California Volcano Monitor is a weekly column written by scientists and collaborators of the California Volcano Observatory. This week's contribution is from Jessica Ball, volcanologist, and Alicia Hotovec-Ellis, geophysicist with the U.S. Geological Survey.

Earthquake swarms are one of the first signs of volcanic activity. Lots of small earthquakes in the same spot over an extended period of time (from hours to even years!) beneath a volcano often means that magma, gas, or hydrothermal fluids are moving through the earth. However, similar earthquake swarms can also happen on faults or in fault zones without a volcano being involved.

How to tell the difference? Consider these questions:

1. Is the swarm near an ACTIVE volcano or geothermal system?

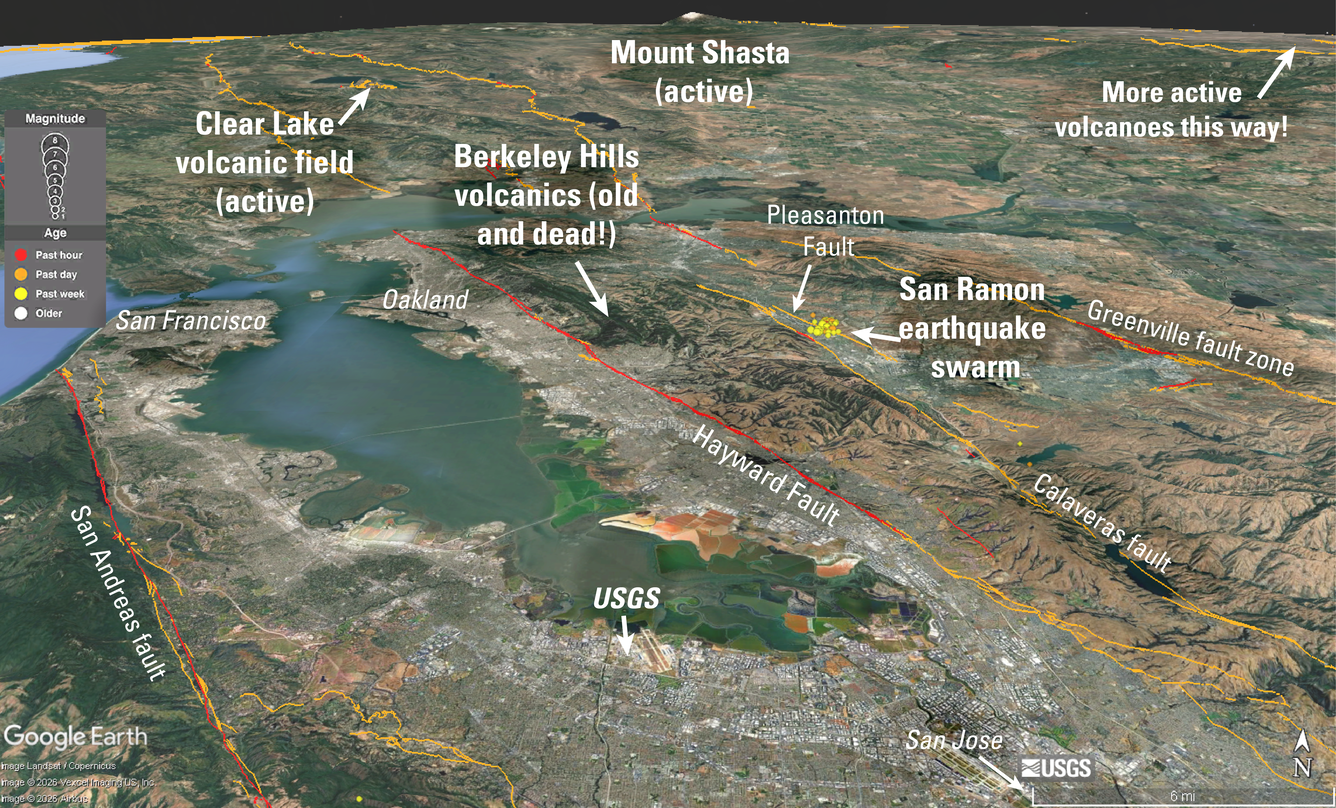

It's easy to check this - use the map on the California Volcano Observatory's webpage (or take a look at the map below). We mark the locations of the active volcanoes we monitor as well as the latest earthquakes. If a group of earthquakes isn't near a volcano or a known geothermal area, it's probably tectonic (that is, due to stresses built up from broad motion of tectonic plates). If it is near a volcano, it might be volcanic in origin, but tectonic earthquakes can happen near volcanoes, too. In the case of the San Ramon swarm, there's no active volcano nearby - the closest volcanic rocks are 5-8 million years old and very cold and dead.

Next, you should consider the pattern of the earthquakes in time:

2. How do the earthquakes’ magnitude and frequency behave over time?

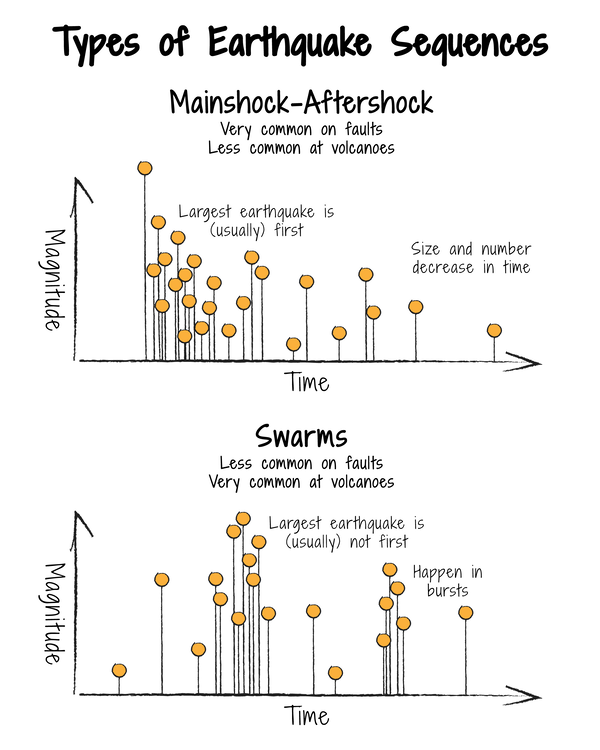

The magnitudes of volcanic earthquake swarms caused by magma or hydrothermal fluids most often don’t have a clear pattern in time: instead, the quakes happen in bursts, waves, or even steady drumbeats. These “swarms” are very common in volcanic areas, even when the volcano isn’t erupting. Tectonic earthquake sequences, on the other hand often follow a very distinct pattern: they usually start with a large "mainshock" followed by many smaller quakes (“aftershocks”) that decrease in magnitude and frequency over time. However, there are instances (like the San Ramon earthquakes) where tectonic earthquake swarms behave similarly to volcanic ones. This is the reason it’s important to take the location into context – if there’s no volcanic system there to begin with, it’s not likely to be a volcanic source.

Because California is full of tectonic faults, it's also worth asking:

3. Have there been earthquake swarms there before?

California is incredibly tectonically active, yet swarms are relatively rare. The “right” conditions for a fault to make a swarm are confined to a few special places, and these areas usually have a long history of swarms that have happened there in the past. Earthquake swarms are common in the San Ramon valley, with similar swarms happening in 2018, 2015, 2003, 2002, 1990, 1976, and 1970.

When the USGS Volcanoes team is reasonably sure that an earthquake swarm is tectonic, we leave the monitoring and reporting to our colleagues in the USGS Earthquake Science Center. Though we're happy to answer questions when we can, tectonic earthquakes are their specialty. We'll be ready and waiting to talk all about our volcanoes when they start shaking!