Paleoscience for Partners: Reconstructing the Past to Prepare for the Future

Scientists from the USGS Ecosystems Land Change Science Program are at the forefront of unraveling mysteries of the past to help partners prepare for future environmental conditions.

Extreme weather events and changes in climate are threatening the integrity of the critical infrastructure and ecosystems that support society. In order to best manage and strengthen the resilience of the built and natural environments, it’s important to understand the full range of potential weather and climate conditions that we could experience. How intense could future atmospheric rivers be? How often could powerful hurricanes make landfall? Instrumental measurements and records of past climate and environmental conditions only cover the past few decades to a century—a microscopic snapshot in Earth’s long history. To truly prepare for the future, we need to look deeper into the past.

Paleoscientists from the Land Change Science Program in the USGS Ecosystems Mission Area are using their expertise to build long-term records of past conditions that are informing the decisions, management options, and future planning of partners across the country.

Preparing Managers for Extreme Precipitation and Weather Disasters

Atmospheric rivers are some of the largest flood-producing extreme precipitation events in western North America, frequently triggering catastrophic flooding and mudslides that damage life and property. However, our understanding of atmospheric river activity has been limited to just 70 years of instrumental data. Scientists from the Land Change Science Program are expanding that record and enhancing hazard preparedness.

Using sediment cores collected from California lakes to reconstruct past atmospheric river activity over the past 3,000 years, scientists found that California has experienced past extreme rainfall events that were larger than those in the modern era.

Understanding just how large historic storms were before our instrumental record is critical for accurately assessing future risk and supporting the construction of resilient infrastructure that can withstand future extreme precipitation events. Many California dams, for example, were designed over 50 years ago and relied on limited climate data. USGS science is offering critical insights for dam managers and local planners, helping to protect lives and reduce future disaster recovery costs.

On the East Coast, Land Change Science Program scientists are using paleorecords from sediment cores to better understand the history of floods and hurricanes. These hazards can have devasting impacts on lives, livelihoods, and ecosystems when they make landfall. Research is helping determine the natural, baseline variability of floods to assist resource managers, improve computer models, and improve natural disaster mitigation. By understanding the frequency and intensity of past cyclones, we can have a better sense of how extreme these storm events can be to help inform coastal planning and development.

In one study, researchers documented the past 2,000 years of hurricanes in northwest Florida and found that existing records of recent storms may underrepresent how often powerful hurricanes have made landfall there. The research supports forecasts by organizations such as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association that the number of intense hurricanes could increase in the future in parts of the Gulf of America and Atlantic Ocean as waters warm. This science can help improve hurricane forecasts and inform state and local policy makers and managers as they prepare plans to protect people, infrastructure, and the environment.

Informing Management of a Key Fishery

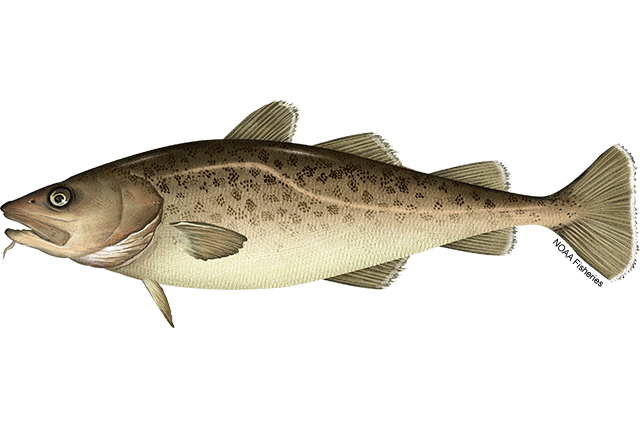

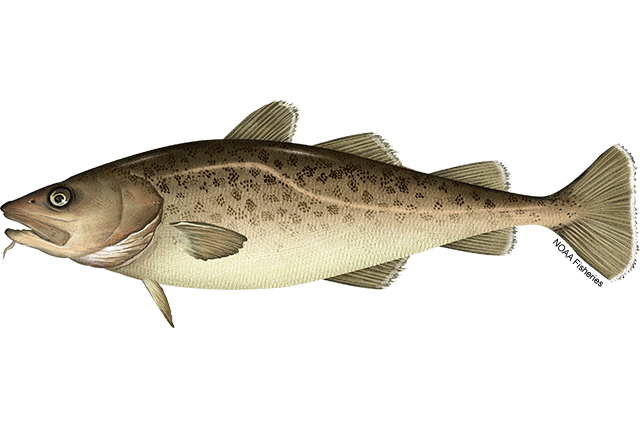

Marine heat waves are prolonged periods when ocean surface waters become unusually warm. One of the most extreme events, known as The Blob, occurred in the North Pacific from 2014 to 2016. It triggered widespread ecological disruption: warm-water species like tropical Pacific hammerhead sharks migrated north to Alaska, cold-water species declined or vanished, and a record-breaking harmful algal bloom emerged.

These ecological disruptions had major socioeconomic impacts. Pacific cod, a \$100M/year commercial fishery in Alaska, declined sharply, prompting a full fishery closure in 2020 — a rare outcome for such a well-managed stock.

A team of academic and federal scientists (NOAA, USGS, and others) combined data from fish stock assessments, environmental data, archaeology and historic records dating back to 1864, and sediment data to understand recent and historical trends in the cod fishery. This research revealed a prior cod collapse (1925–1945) linked to warming, overfishing, and reduced demand. This research is helping inform the management of the Pacific cod fishery to stabilize this fishery at sustainable levels.

Rebuilding Healthy Shellfish Populations

The expanding shellfish industry of the eastern U.S. and Florida relies heavily on oysters and hard clams. Researchers with the Land Change Science Program are studying shells, in collaboration with industry partners, to identify the temperature limits that key commercial shellfish species can tolerate, how fast they grow, and what conditions they will need to thrive in the future.

Scientists are analyzing the chemistry and growth patterns in shells to reconstruct past water temperature and salinity that modern and prehistoric clams experienced. This long-term baseline knowledge helps farmers and resource managers make more informed decisions about where and how to restore shellfish beds and run aquaculture operations in the future—especially if waters continue to warm and harmful events like red tide become more common. It also enriches understanding of the climate history of the Gulf Coast. The goal is to provide reliable, science-based guidance to support, conserve, and rebuild healthy shellfish populations for the people and industries that rely on them.

Helping Coastal Communities Prepare for Extreme Floods and Sea Level Rise Hazards

Northeastern cities face higher 100-year flood risks than almost any other stretch of U.S. coast. Often located at the head of estuaries, these cities are subject to storm-surge inundation from hurricanes and nor'easters as well as river flooding and sea level rise. Flood mitigation strategies in these areas rely on relatively short stream and tide-gauge observations that oftentimes do not capture infrequent, but extreme, flood events or long-term changes in sea level. Decision-makers at all levels need baseline information on high water extremes to ensure public safety during storm events.

To address these needs, scientists with the Land Change Science Program are studying the frequency and intensity of pre-historic floods and droughts as well as sea level rise along the East Coast. For example, scientists combined historic observations with a geologic proxy reconstruction to produce records of flooding and sea level at Washington, D.C. spanning more than 500 years.

These data are being used by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the D.C. Department of Energy and Environment, and others as part of an interagency effort to improve public awareness and preparedness for extreme floods and rainfall events in the District of Columbia.

Reconstructing Past Hydrologic History to Understand Floods, Fire, Landslides, and Water Availability

Climate model forecasts indicate that the western U.S. will experience more frequent extreme hydrologic events, such as floods and droughts, in the future. While instrumental records from the past ~100 years provide some context for precipitation patterns, these records are often too short to capture the full range of natural hydrologic and climatic variability.

To better understand the potential consequences of future changes in climate, USGS scientists are studying extreme weather and climate events that happened in the past, how big they were, and what effects they had in the region.

For example, scientists are using data from a network of sites from across the central Pacific, coastal California, and the Pacific Northwest that preserve geologic records of past conditions associated with north Pacific climate dynamics to reconstruct a high-resolution, detailed timeline of past climate. The resulting data help managers assess the likely impacts of future climate change on terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems and better predict and plan for future conditions like fire magnitude and frequency, natural hazards, and water quality and availability.

In a second project focused on the arid mountain west, scientists are using lake sediments to better understand patterns of extreme precipitation and drought. By developing long-term baselines in precipitation that overlap with the past century of instrumental data, scientists are able to document pre-historical extremes that surpass modern observations. This project also leverages the preservation of signals of past natural disasters in lake sediments, like floods, landslides, earthquakes, and wildfires, to extend our record of these events. Combining these long-term data improves forecasting and risk assessments that help protect critical infrastructure, forests, the water supply, and other resources, particularly those managed by the Department of the Interior.

A third project focuses on natural springs and wetlands that can be found throughout the arid West. These unique ecosystems are exceptionally sensitive to drought and other hydrologic changes and are indicators of the health of aquifers that provide freshwater to surrounding plants, wildlife, and human populations. To better understand spring ecosystems and their role in the water cycle, scientists are investigating outcrops of ancient wetland deposits and collecting core samples from active springs to reconstruct the hydrologic history of the region and understand how groundwater levels have changed over time.

The results will provide critical information for developing strategies to manage fragile wetland ecosystems in the arid lands of the Southwest. By improving our understanding of how springs and wetlands in the Mojave Desert responded to past abrupt warming events, we can develop a roadmap of potential responses to changing conditions to inform decision-making and water resource planning today.

Understanding Past Wetland Extent, Processes, and Drivers of Change

Wetlands offer many benefits to society, providing habitats for fish and wildlife, buffering storm surge, storing carbon, and filtering contaminants. Scientists with the Land Change Science Program are exploring how wetlands have been affected by environmental- and human-driven changes, such as wetland drainage, drought, fire, and coastal inundation. By analyzing soil and sediment cores, they’re able to reconstruct past wetland conditions to better understand historic changes in plant communities and fire regimes associated with changing hydrologic conditions.

By combining new paleoenvironmental data with monitoring and instrumental data from long-term study sites in wetlands on the Gulf and Atlantic coasts, Alaska, Hawaii, and the Pacific Islands, this project is generating data on long-term vegetation and fire regimes that provide managers with new information on the hydrologic and disturbance regimes needed to maintain well-functioning wetlands. Resource managers are using these data to inform future policy decisions on land and water management, restoration, and protection in coastal zones.

Learn More

The USGS is home to one of the largest, most multidisciplinary groups of scientists who unravel mysteries of the past, and help project future patterns, by studying paleoclimate. Learn more about the powerhouse of USGS paleo-research.

Scientists from the USGS Ecosystems Land Change Science Program are at the forefront of unraveling mysteries of the past to help partners prepare for future environmental conditions.

Extreme weather events and changes in climate are threatening the integrity of the critical infrastructure and ecosystems that support society. In order to best manage and strengthen the resilience of the built and natural environments, it’s important to understand the full range of potential weather and climate conditions that we could experience. How intense could future atmospheric rivers be? How often could powerful hurricanes make landfall? Instrumental measurements and records of past climate and environmental conditions only cover the past few decades to a century—a microscopic snapshot in Earth’s long history. To truly prepare for the future, we need to look deeper into the past.

Paleoscientists from the Land Change Science Program in the USGS Ecosystems Mission Area are using their expertise to build long-term records of past conditions that are informing the decisions, management options, and future planning of partners across the country.

Preparing Managers for Extreme Precipitation and Weather Disasters

Atmospheric rivers are some of the largest flood-producing extreme precipitation events in western North America, frequently triggering catastrophic flooding and mudslides that damage life and property. However, our understanding of atmospheric river activity has been limited to just 70 years of instrumental data. Scientists from the Land Change Science Program are expanding that record and enhancing hazard preparedness.

Using sediment cores collected from California lakes to reconstruct past atmospheric river activity over the past 3,000 years, scientists found that California has experienced past extreme rainfall events that were larger than those in the modern era.

Understanding just how large historic storms were before our instrumental record is critical for accurately assessing future risk and supporting the construction of resilient infrastructure that can withstand future extreme precipitation events. Many California dams, for example, were designed over 50 years ago and relied on limited climate data. USGS science is offering critical insights for dam managers and local planners, helping to protect lives and reduce future disaster recovery costs.

On the East Coast, Land Change Science Program scientists are using paleorecords from sediment cores to better understand the history of floods and hurricanes. These hazards can have devasting impacts on lives, livelihoods, and ecosystems when they make landfall. Research is helping determine the natural, baseline variability of floods to assist resource managers, improve computer models, and improve natural disaster mitigation. By understanding the frequency and intensity of past cyclones, we can have a better sense of how extreme these storm events can be to help inform coastal planning and development.

In one study, researchers documented the past 2,000 years of hurricanes in northwest Florida and found that existing records of recent storms may underrepresent how often powerful hurricanes have made landfall there. The research supports forecasts by organizations such as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association that the number of intense hurricanes could increase in the future in parts of the Gulf of America and Atlantic Ocean as waters warm. This science can help improve hurricane forecasts and inform state and local policy makers and managers as they prepare plans to protect people, infrastructure, and the environment.

Informing Management of a Key Fishery

Marine heat waves are prolonged periods when ocean surface waters become unusually warm. One of the most extreme events, known as The Blob, occurred in the North Pacific from 2014 to 2016. It triggered widespread ecological disruption: warm-water species like tropical Pacific hammerhead sharks migrated north to Alaska, cold-water species declined or vanished, and a record-breaking harmful algal bloom emerged.

These ecological disruptions had major socioeconomic impacts. Pacific cod, a \$100M/year commercial fishery in Alaska, declined sharply, prompting a full fishery closure in 2020 — a rare outcome for such a well-managed stock.

A team of academic and federal scientists (NOAA, USGS, and others) combined data from fish stock assessments, environmental data, archaeology and historic records dating back to 1864, and sediment data to understand recent and historical trends in the cod fishery. This research revealed a prior cod collapse (1925–1945) linked to warming, overfishing, and reduced demand. This research is helping inform the management of the Pacific cod fishery to stabilize this fishery at sustainable levels.

Rebuilding Healthy Shellfish Populations

The expanding shellfish industry of the eastern U.S. and Florida relies heavily on oysters and hard clams. Researchers with the Land Change Science Program are studying shells, in collaboration with industry partners, to identify the temperature limits that key commercial shellfish species can tolerate, how fast they grow, and what conditions they will need to thrive in the future.

Scientists are analyzing the chemistry and growth patterns in shells to reconstruct past water temperature and salinity that modern and prehistoric clams experienced. This long-term baseline knowledge helps farmers and resource managers make more informed decisions about where and how to restore shellfish beds and run aquaculture operations in the future—especially if waters continue to warm and harmful events like red tide become more common. It also enriches understanding of the climate history of the Gulf Coast. The goal is to provide reliable, science-based guidance to support, conserve, and rebuild healthy shellfish populations for the people and industries that rely on them.

Helping Coastal Communities Prepare for Extreme Floods and Sea Level Rise Hazards

Northeastern cities face higher 100-year flood risks than almost any other stretch of U.S. coast. Often located at the head of estuaries, these cities are subject to storm-surge inundation from hurricanes and nor'easters as well as river flooding and sea level rise. Flood mitigation strategies in these areas rely on relatively short stream and tide-gauge observations that oftentimes do not capture infrequent, but extreme, flood events or long-term changes in sea level. Decision-makers at all levels need baseline information on high water extremes to ensure public safety during storm events.

To address these needs, scientists with the Land Change Science Program are studying the frequency and intensity of pre-historic floods and droughts as well as sea level rise along the East Coast. For example, scientists combined historic observations with a geologic proxy reconstruction to produce records of flooding and sea level at Washington, D.C. spanning more than 500 years.

These data are being used by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the D.C. Department of Energy and Environment, and others as part of an interagency effort to improve public awareness and preparedness for extreme floods and rainfall events in the District of Columbia.

Reconstructing Past Hydrologic History to Understand Floods, Fire, Landslides, and Water Availability

Climate model forecasts indicate that the western U.S. will experience more frequent extreme hydrologic events, such as floods and droughts, in the future. While instrumental records from the past ~100 years provide some context for precipitation patterns, these records are often too short to capture the full range of natural hydrologic and climatic variability.

To better understand the potential consequences of future changes in climate, USGS scientists are studying extreme weather and climate events that happened in the past, how big they were, and what effects they had in the region.

For example, scientists are using data from a network of sites from across the central Pacific, coastal California, and the Pacific Northwest that preserve geologic records of past conditions associated with north Pacific climate dynamics to reconstruct a high-resolution, detailed timeline of past climate. The resulting data help managers assess the likely impacts of future climate change on terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems and better predict and plan for future conditions like fire magnitude and frequency, natural hazards, and water quality and availability.

In a second project focused on the arid mountain west, scientists are using lake sediments to better understand patterns of extreme precipitation and drought. By developing long-term baselines in precipitation that overlap with the past century of instrumental data, scientists are able to document pre-historical extremes that surpass modern observations. This project also leverages the preservation of signals of past natural disasters in lake sediments, like floods, landslides, earthquakes, and wildfires, to extend our record of these events. Combining these long-term data improves forecasting and risk assessments that help protect critical infrastructure, forests, the water supply, and other resources, particularly those managed by the Department of the Interior.

A third project focuses on natural springs and wetlands that can be found throughout the arid West. These unique ecosystems are exceptionally sensitive to drought and other hydrologic changes and are indicators of the health of aquifers that provide freshwater to surrounding plants, wildlife, and human populations. To better understand spring ecosystems and their role in the water cycle, scientists are investigating outcrops of ancient wetland deposits and collecting core samples from active springs to reconstruct the hydrologic history of the region and understand how groundwater levels have changed over time.

The results will provide critical information for developing strategies to manage fragile wetland ecosystems in the arid lands of the Southwest. By improving our understanding of how springs and wetlands in the Mojave Desert responded to past abrupt warming events, we can develop a roadmap of potential responses to changing conditions to inform decision-making and water resource planning today.

Understanding Past Wetland Extent, Processes, and Drivers of Change

Wetlands offer many benefits to society, providing habitats for fish and wildlife, buffering storm surge, storing carbon, and filtering contaminants. Scientists with the Land Change Science Program are exploring how wetlands have been affected by environmental- and human-driven changes, such as wetland drainage, drought, fire, and coastal inundation. By analyzing soil and sediment cores, they’re able to reconstruct past wetland conditions to better understand historic changes in plant communities and fire regimes associated with changing hydrologic conditions.

By combining new paleoenvironmental data with monitoring and instrumental data from long-term study sites in wetlands on the Gulf and Atlantic coasts, Alaska, Hawaii, and the Pacific Islands, this project is generating data on long-term vegetation and fire regimes that provide managers with new information on the hydrologic and disturbance regimes needed to maintain well-functioning wetlands. Resource managers are using these data to inform future policy decisions on land and water management, restoration, and protection in coastal zones.

Learn More

The USGS is home to one of the largest, most multidisciplinary groups of scientists who unravel mysteries of the past, and help project future patterns, by studying paleoclimate. Learn more about the powerhouse of USGS paleo-research.