Assembling a seismic history of the southern San Andreas Fault Zone beneath Salton Sea

The San Andreas Fault stretches for 750 miles along much of the length of California, traveling belowground from the Bay Area south to the Salton Sea. It marks the tectonic boundary of the Pacific and North American plates as they slide horizontally past one another, 20 to 35 millimeters (0.8 to 1.4 inches) per year.

The San Andreas Fault, along with others associated with it, has produced some of the largest earthquakes in California’s history.

To better understand the fault’s characteristics and potential earthquake hazards, for decades researchers have worked to assemble a detailed history of seismic activity along its northern and central reaches; it is only recently that attention has turned to the fault’s southern terminus, beneath the Salton Sea.

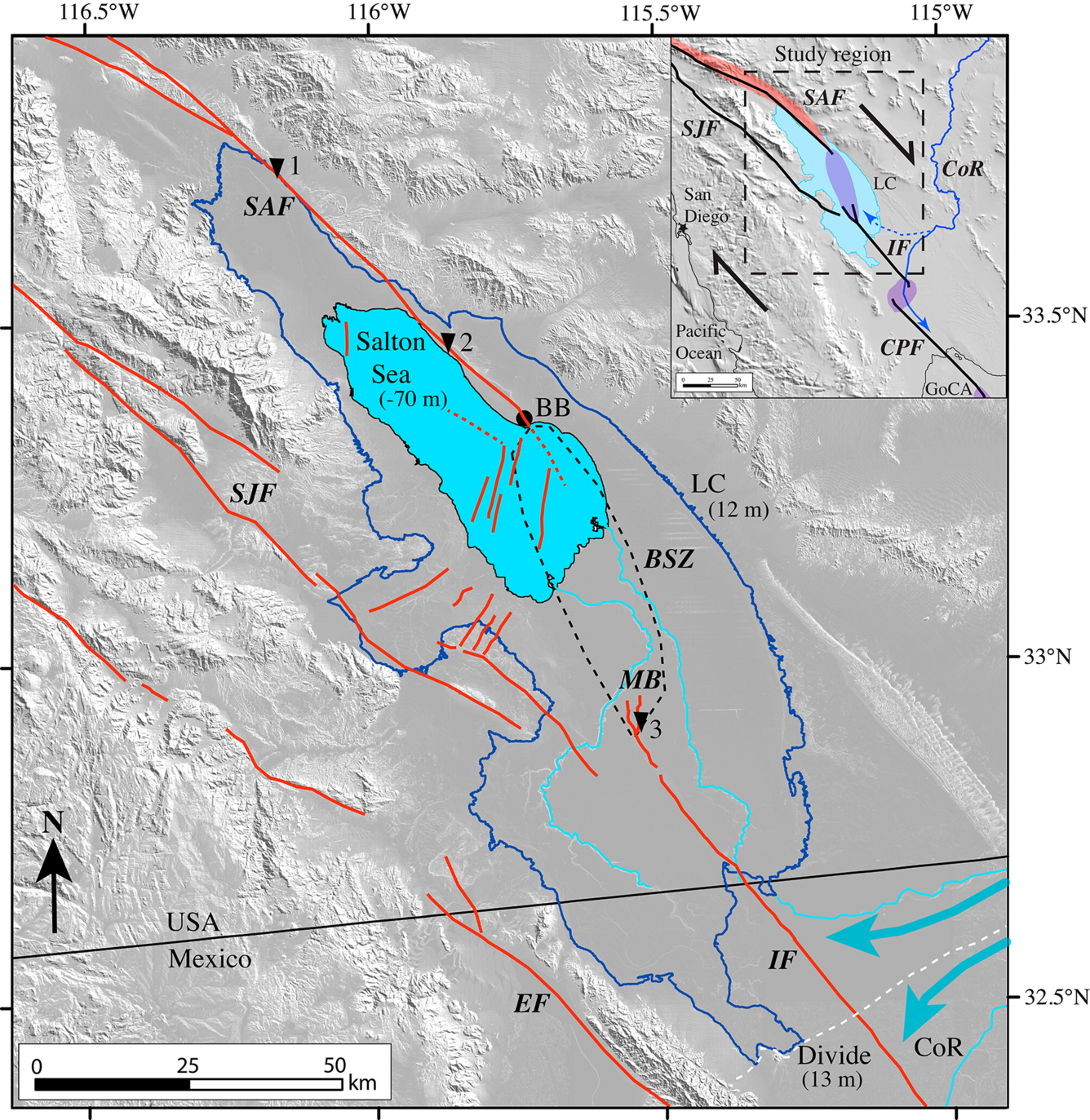

Seismic activity at Salton Sea could potentially trigger large earthquakes along the length of the San Andreas Fault. Despite knowledge of this hazard, the distribution of active faults in the Salton Sea was for years only roughly defined. A recent study from researchers at the USGS Pacific Coastal and Marine Science Center, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, and the Nevada Seismological Laboratory uses sonar and sediment coring to characterize the full network of faults in the Salton Sea, a crucial step toward reconstructing the region's earthquake history and assessing future seismic hazards.

A sea in the desert

At some point in the late Holocene, more than 3,000 years ago, a wide, shallow basin known as the Salton Trough in southern California began to periodically fill with Colorado River flood waters, creating the ancient Lake Cahuilla. The lake would cycle through periods of filling and desiccation as the river switched back and forth between spilling into the Salton Trough and the Sea of Cortez. By the early 1700s, this filling/drying cycle had all but ceased.

Almost 200 years later, in an unusual turn of events, the lake was revived. In 1905, during a period of intense flooding along the Colorado River, a canal diverting the overflowing river failed, filling the Salton Trough with water. The canal wasn’t fixed for two years, by which point the lake’s surface area had grown to 970 square kilometers (375 square miles), making it the largest lake in California. As it became clear that the lake wasn’t going anywhere anytime soon, it was named the Salton Sea.

For a brief period, the Salton Sea was considered a vacation destination for southern Californians wishing to boat and fish in the Mojave Desert. It also became a haven for migratory birds along the Pacific Flyway, providing crucial habitat at a time when the extensive wetlands of the Central Valley were rapidly being converted to agriculture.

But the Salton Sea, having no outlet and very little freshwater input, is becoming increasingly saline and stagnant as it slowly shrinks. In the nearby Imperial Valley, water diverted from the Colorado River for agriculture eventually runs down into the Sea, carrying salt, heavy metals, agricultural chemicals, and excess nutrients, which can concentrate to toxic levels. In some years fish and birds die in staggering numbers; developers and tourists have long since abandoned the area.

As a decades-long drought continues to afflict the Colorado River Basin, further reducing water diversions into the Imperial Valley, the future of Salton Sea is uncertain.

Before restoration, assess seismic risk

As more of its shoreline is exposed to drying wind and heat, toxins in the sediment become airborne as dust and can pose significant health risks to neighboring communities. The state of California has long considered plans to restore ecosystem functions and mitigate health hazards at Salton Sea, but there remained a lack of basic knowledge about tectonic activity in the area.

“Before anyone can do the engineering work required for these restoration projects, they have to know where active faults are located, their history of movement, what the geotechnical properties are of the sediment they’re building on, and so forth,” said Danny Brothers, USGS Research Geophysicist and lead author of the study. “This study lays out where many of the faults in the sea are located and begins to build a seismic history of this area—all of which are likely to have implications for any kind of Salton Sea restoration plan that's proposed.”

The study represents the most comprehensive investigation of late Holocene tectonic activity and Lake Cahuilla sedimentation history in the Salton Sea. The next step, Brothers says, is to obtain longer lakebed sediment cores along these faults—longer cores go further back in time—and radiometrically date them, to create a detailed chronological record of earthquakes in the area. With this record, researchers can better understand the frequency, intensity, and possible recurrence of seismic activity at Salton Sea.