Biophysical controls on sediment erodibility in San Francisco Bay

The erodibility of bed sediment in estuaries can shape everything from water clarity to habitat quality, and influences the magnitude of sediment transport. While scientists largely understand how bed sediments in sandy environments erode, less attention has focused on muddy sediments in estuaries. New research from USGS shows that waves matter—but so do the animals living in the mud.

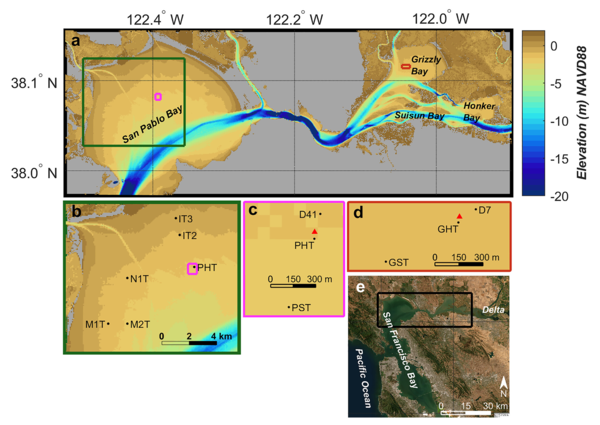

In a study conducted in the shallow waters of San Pablo Bay and Grizzly Bay in northern San Francisco Bay, scientists investigated what controls the erodibility of muddy sediments—how readily they are mobilized from the bayfloor and stirred up into the water column. The team collected detailed measurements during both summer 2019 and winter 2020, capturing seasonal contrasts in physical conditions and biological activity.

Using instruments deployed directly on the bayfloor, researchers tracked waves, currents, and suspended sediment concentrations over time. From these data, they calculated an erosion-rate parameter that quantifies how easily sediments are resuspended. In addition, samples of the seabed were collected to analyze sediment properties—such as grain size, density, and organic content—and to catalog the type and abundance of benthic animals living in the mud.

Across both bays, one physical driver stood out: waves. Stronger wave-driven shear stress consistently increased sediment erodibility, confirming that even in relatively sheltered estuaries, wave action plays a key role in mobilizing muddy bottoms.

However, in San Pablo Bay, sediments were about 50 percent less erodible in winter than in summer—a seasonal shift that could not be explained by waves or sediment properties alone. Instead, changes in the type and abundance of benthic animals, such as crustaceans, clams, and other invertebrates that live in or on the sediment, appeared to significantly alter how easily mud could be eroded. The lower erodibility in winter was attributed to increased abundance of the amphipod Ampelisca abdita, which creates small tubes in the sediment that can form dense mats, reducing the mobilization of bed sediment. In contrast, Grizzly Bay showed no strong seasonal change in erodibility, highlighting how local ecological differences can shape sediment behavior.

These findings underscore that muddy bay sediments are not just passive materials shaped by physics. They are living systems, where animals—both native and introduced—can stabilize or loosen sediments in ways that influence water clarity, nutrient transport, and habitat conditions. The results present a challenge to numerical models of sediment transport, which require specification of an erosion rate parameter.

Read the study, Biophysical Controls on Sediment Erodibility in Shallow Estuarine Embayments, in JGR Biogeosciences.