Characterizing Organic Carbon Cycling at a Seafloor Spreading Center

New research from USGS characterizes organic carbon cycling in deep-sea sediments collected at Escanaba Trough, a unique seafloor spreading area which may contain critical minerals almost 322 kilometers (200 miles) offshore of northern California.

The global ocean is a significant carbon sink, absorbing about a third of all atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions (Gruber et al., 2019). Much of that carbon is photosynthesized—that is, converted into organic matter—and may eventually reach the seafloor, where it becomes part of the sediments. Globally, the top one meter (3.3 feet) of the seafloor contains two and a half times as much carbon as all atmospheric CO2 (Atwood et al., 2020). However, relatively few studies have looked at organic carbon cycling in deep-sea settings, largely due to the difficulty of conducting research there.

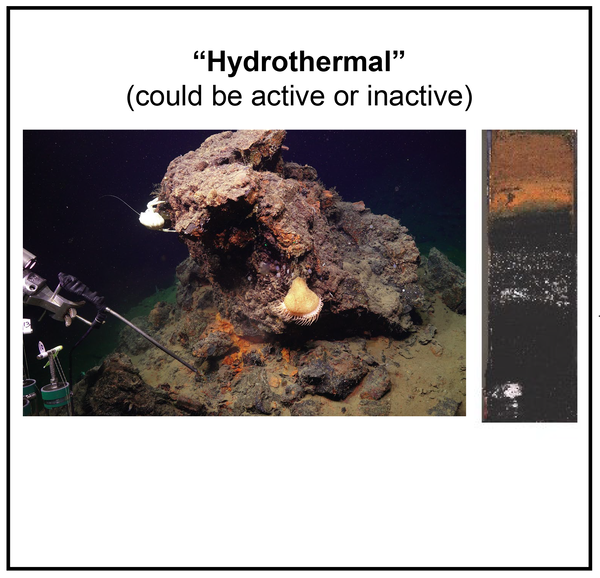

In this recent study, USGS researchers characterized carbon-containing compounds in sediments from Escanaba Trough, a hydrothermal system where mineral-rich fluids vent from the seafloor and precipitate, forming active chimneys, inactive sulfide mounds, and hydrocarbon-rich sediments, which can contain metals, critical minerals, and petroleum. The venting fluids also feed chemosynthetic organisms that create energy from hydrothermal chemicals rather than light, giving rise to entire deep-sea ecosystems in the cold, dark depths.

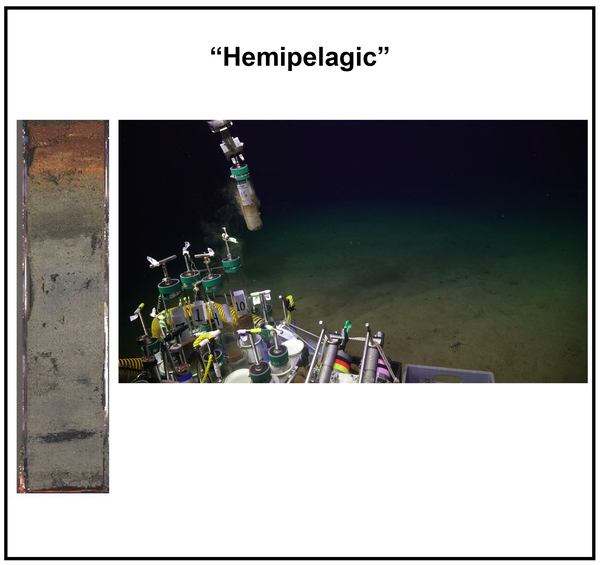

Sediments within Escanaba Trough enhance the preservation of potentially critical minerals and formation of petroleum. The researchers found that surface sediments—those that were most recently deposited—at the site are primarily derived from marine sources. This contrasts with past work done in this environment, which focused on sediments deeper down, with a predominantly terrestrial source. This older, land-sourced sediment, which covers Escanaba Trough to depths of up to 500 meters, is attributed to post-glacial debris flows, or turbidites, caused by ice sheets retreating across North America during the end of the last Ice Age. After the ice sheets melted, the sediment source shifted to organic carbon derived from marine primary production, in which photosynthetic organisms convert inorganic carbon to organic material that may ultimately descend to the seafloor as sediment.

Sediment cores collected near and far from hydrothermal vents

Another notable aspect of the study looked at the extent to which organic carbon is labile, or available to organisms to consume, in this system. Labile organic carbon is likely to support deep-sea communities, while so-called refractory organic carbon is less likely to be consumed. The researchers suggest that sediments at inactive vents contained greater quantities of labile organic carbon than at active vents, which they attributed to hydrothermal alteration—essentially, the labile carbon is transformed by contact with hot hydrothermal fluids at active vents, a process that can also lead to petroleum formation. Indeed, the researchers found evidence of rapid (compared to geological timescales) production and preservation of petroleum which varied with vent temperature, improving our understanding of petroleum formation at hydrothermal vents.

“A goal of this work is to go to sites where we simply don't have a lot of baseline data, because the deep sea is so understudied,” said Hope Ianiri, USGS Research Chemist and lead author of the study. “A lot of what we aim to do is better understand how a system like Escanaba Trough works at its baseline state, so that we have that information to compare to in case conditions were to change.”

This work adds to our understanding of environmental settings that may contain minerals necessary for battery technology, national security, and more.

Read the study, Characterizing sedimentary organic carbon in a hydrothermal spreading center, the Escanaba Trough, in Chemical Geology.