From Egg to Adult: WFRC’s Work to Support California’s Chinook Salmon Population

WFRC research provides critical insights into salmon recovery in California’s Sacramento River.

Sacramento River Chinook salmon populations have been a vital part of California’s Central Valley for thousands of years, with both Indigenous populations and European settlers relying on the fish for food and economy. But as early as the 1860s, overharvest and habitat loss had begun to reduce Chinook populations – eventually leading to the listing of some Central Valley Chinook salmon as an endangered species in 1989.

Today, scientists at the USGS Western Fisheries Research Center (WFRC) are working to understand what drives Chinook salmon health, providing research to support water management in the Central Valley for both fish and people. WFRC is focused on identifying the challenges salmon face at every stage of their lives — from egg to adult — to deliver science that informs resource managers.

California’s Salmon Face Multiple Challenges

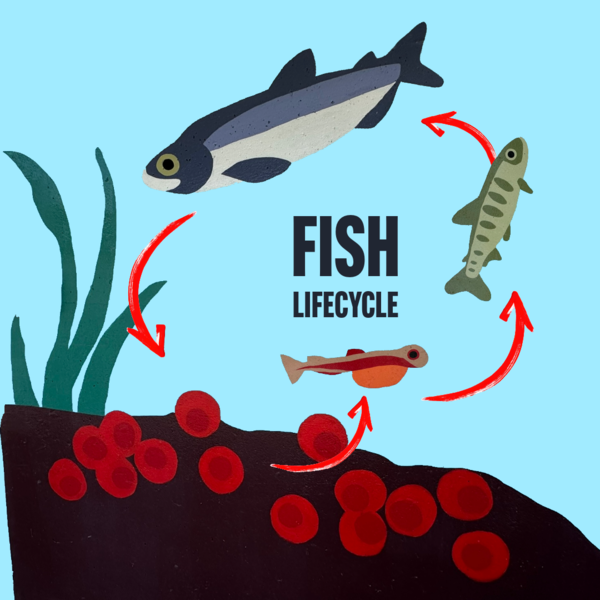

Chinook salmon are a vital part of California’s Central Valley, supporting both rich ecosystems and local economies. However, these fish face challenges at every stage of their life cycle—from tiny eggs nestled in river gravel to adults making their long journey back from the ocean to spawn. Over the past century, the natural rivers of the region have been transformed by human activities, with dams, water diversions, and irrigation networks significantly altering flows and blocking traditional migration routes. These changes affect not only where salmon can reproduce but also how successfully juveniles navigate their way downstream to the ocean.

Two of the most significant barriers in this system are Shasta and Keswick dams, built in the mid-20th century to meet growing demands for water storage and hydroelectric power. Shasta Dam was completed in 1945 and Keswick Dam in 1950, both playing key roles in California’s water management. Yet, while these dams support agriculture and urban development, they have also disrupted the natural flow of the Sacramento River and blocked the migration paths of Chinook salmon and other native fish species, limiting access to important upstream habitats.

To address these complex challenges, researchers at WFRC are studying Chinook salmon throughout their entire life cycle. By combining advanced tracking technology, ecological research, and advanced modeling, WFRC scientists are gaining a deeper understanding of how dams, water diversions, and habitat changes impact salmon survival and migration—from eggs in the gravel to adults returning to spawn. This holistic research approach provides critical insights that can help guide efforts to protect and restore Chinook salmon populations across California’s Central Valley.

California Department of Fish & Wildlife boat on Shasta Reservoir partnering with USGS Western Fisheries Research Center to conduct telemetry studies.

Understanding Egg Survival and River Conditions

Water released from Shasta and Keswick dams upriver of Chinook salmon redds plays a pivotal role in shaping the river's temperature and volume, creating conditions that can either nurture or jeopardize the survival of these salmon eggs. Uncovering how variations in water management influence the reproductive success of Chinook salmon is therefore critical.

WFRC scientist John Plumb, alongside the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, is working to identify salmon egg survival varies under different water management regimes, deploying “artificial redds”—special boxes containing salmon eggs—at multiple sites along the river. Each box is fit with sensors that measure critical variables including temperature, oxygen levels, and sedimentation – information that can help decode how water released from upstream dams may influence egg survival. As the eggs hatch, the team will return to the sites to count how many juvenile salmon survived, giving insight into the environmental conditions that best favored egg development. This information can help resource managers understand how water allocation from upstream dams impacts young salmon in the Sacramento. By adjusting the flow from the dams, it may be possible to improve hatch rates and give the young salmon a better start in life.

Scientists conducting research in the field near the Sacramento River, CA.

Tracking Juvenile Migration Downstream to the Ocean

As young salmon grow from tiny, yolk-carrying alevin into free-swimming fry, they leave the safety of their gravel nests and begin to explore the river. Still small and easy prey for predators, they spend much of their early days darting between rocks and hiding in calm pools. After a few months, these Chinook salmon are ready to begin their migration toward the ocean, a critical step in their path to adulthood.

In California’s Central Valley, this journey – known as outmigration – is anything but straightforward. Young salmon must navigate a maze of obstacles, from towering dams to complex irrigation channels, all of which can block or divert their natural route to the sea.

In the Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta, understanding how juvenile Chinook salmon move through the complex network of river channels and irrigation diversions is essential for improving their chances of survival. To tackle this challenge, scientists at WFRC are combining acoustic tagging with advanced quantitative modeling. By implanting tiny acoustic transmitters into juvenile salmon, researchers can track their precise movements through the Delta in real time. These rich datasets are then fed into quantitative models, which allow scientists to estimate survival rates, travel times, and the likelihood of fish choosing certain migration routes.

This approach has revealed that no single environmental factor—like water flow or tidal conditions—predicts salmon survival across the entire Delta. Instead, different regions show different patterns, emphasizing the importance of localized management strategies. These insights are critical for shaping water operations and habitat restoration efforts aimed at supporting salmon recovery.

WFRC researchers are also working with the California Department of Water Resources to test new tools that can help guide salmon away from dangerous routes. Among the potential solutions is a BioAcoustic Fish Fence (BAFF), currently being evaluated at Georgiana Slough—a site where many young salmon are diverted into suboptimal channels. A BAFF creates a barrier using a combination of sound, air bubbles, and light to steer fish away from hazardous paths without physically obstructing the waterway. This system takes advantage of salmon’s sensitivity to specific acoustic cues, redirecting them toward safer migration corridors while still allowing for boat navigation and water deliveries. WFRC scientists help evaluate how fish respond to the BAFF at Georgiana Slough, providing information to resource managers as they work to divert fish from channels with lower survival rates.

By combining acoustic tagging with sophisticated modeling, researchers at WFRC are not only identifying which routes salmon take through the Delta but also uncovering where survival breaks down—and why. These insights help pinpoint where targeted interventions could make the biggest difference. For example, adjusting the timing or volume of water flows might help guide more fish along safer routes, while reducing exposure to warm, stagnant waters that increase the risk of disease, such as the parasite Ceratonova shasta.

These research efforts offer a science-based understanding of how juvenile Chinook salmon migrate through the Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta and what factors influence their survival. With this information, WFRC supports water resource managers by identifying where environmental conditions may be optimized to improve salmon survival.

This is the Bio-Acoustic Fish Fence (BAFF) Barrier in the Georgiana Slough.

Title

Title

Challenges and Opportunities for Adult Salmon on Their Journey Home

As Chinook salmon complete their remarkable migration from the ocean back to their natal streams, they face some of the greatest challenges of their life cycle. In California’s Central Valley, many historic spawning grounds lie above large dams like Shasta, which block access to the cold, upstream waters these fish once relied on. Without access to these critical habitats, adult salmon returning to spawn must settle for less suitable locations downstream, where warmer water temperatures can reduce spawning success and egg survival.

To explore long-term solutions, WFRC scientist Tobias Kock is working with the Winnemem Wintu Tribe to study juvenile salmon movement in areas above Shasta Dam. By understanding how fish migrate in these historically important habitats, researchers can evaluate whether fish passage—restoring a route over or around the dam—could be an effective strategy for reestablishing access to high-quality spawning grounds.

In parallel with this work, WFRC scientists Jill Hardiman, Tobias Kock, Shelley Johnson, Jan Lovy, and Carl Ostberg are also investigating a novel restoration approach: the potential reintroduction of Chinook salmon from New Zealand. These salmon, originally introduced from California in the early 1900s, have thrived in New Zealand’s rivers for over a century. Researchers are now examining whether these long-separated populations could help restore declining runs in California. The team is conducting a comprehensive risk assessment, including genetic comparisons, ecological compatibility, food web dynamics in Shasta Lake, and potential disease concerns. This science will inform whether New Zealand-origin salmon could safely and successfully contribute to rebuilding self-sustaining Chinook populations in the Sacramento River system. Results from the assessment are expected in late 2025.

A photo of the McCloud arm looking upstream from one of the telemetry deployment sites.

The Path Ahead: Supporting Informed Decisions Across the Salmon Life Cycle

Chinook salmon recovery in California involves complex challenges that require detailed scientific understanding. The work conducted by WFRC scientists—ranging from monitoring egg survival and tracking juvenile migration to assessing innovative restoration strategies—provides essential data and analyses. These findings support resource managers and decision-makers by offering objective information about salmon biology, habitat conditions, and potential restoration options. Through continued research and collaboration, WFRC aims to equip those responsible for managing water resources with the knowledge needed to make informed decisions about Chinook salmon conservation in the Sacramento River and beyond.