The Science of Suckers: What’s driving population declines in the Klamath River basin?

USGS and its partners are working tirelessly to monitor suckers and understand why they are disappearing from lakes and streams in the Klamath River Basin

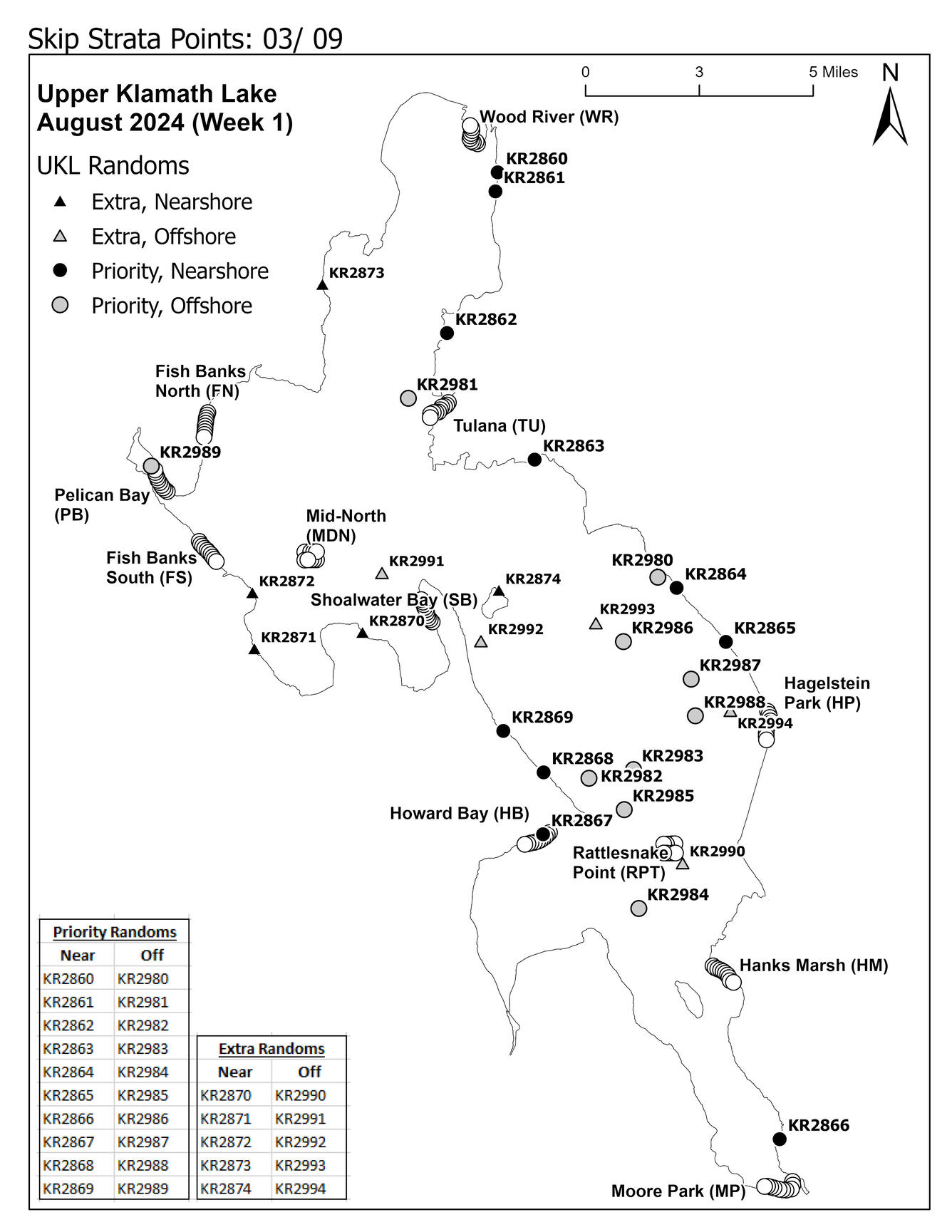

Its early morning as we pass a green expanse of farmland and pull into a parking lot with a boat ramp sloping into the massive waters of Upper Klamath Lake. Paving machines drone next to us, widening the road winding along the lake shore. A thick haze of yellow-brown wildfire smoke hangs in the air, obscuring faint outlines of the high peaks surrounding Crater Lake across the water. A swarm of midges and sea of algae greet us as we load our boat. We pack up, leave shore, and head toward our first target—a set of trap nets--with tempered hopes of finding something exceedingly rare: evidence of surviving juvenile suckers.

WFRC scientists are working tirelessly to identify the factors driving the loss of juvenile suckers. Though the problem is complex, our researchers have plans to continue to home in on why juvenile suckers are dying in such large numbers.

A sign of life and livelihood

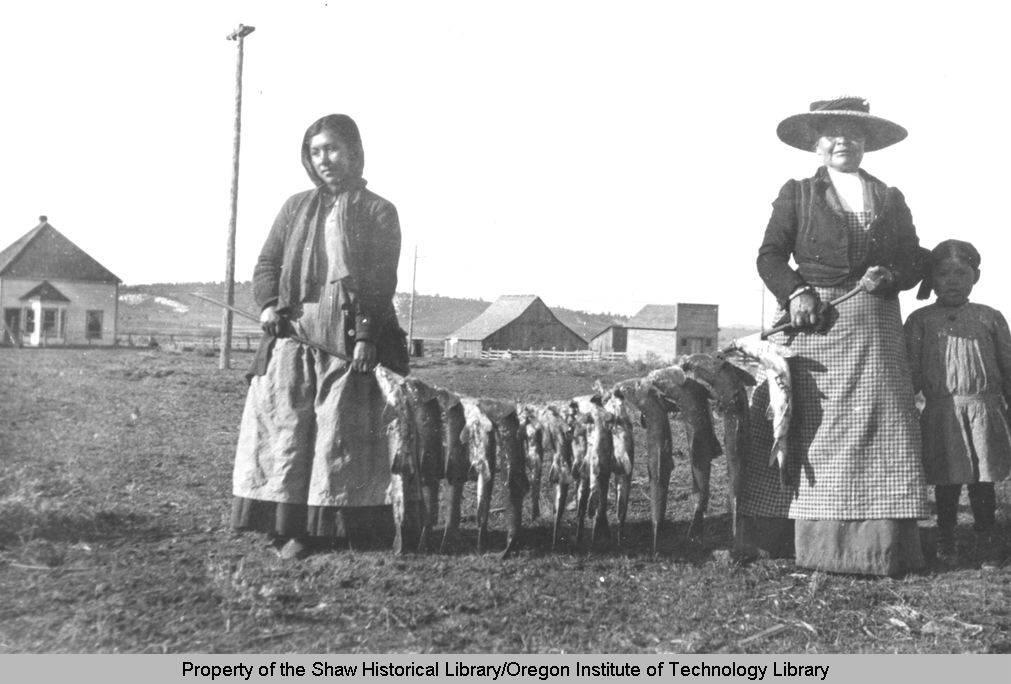

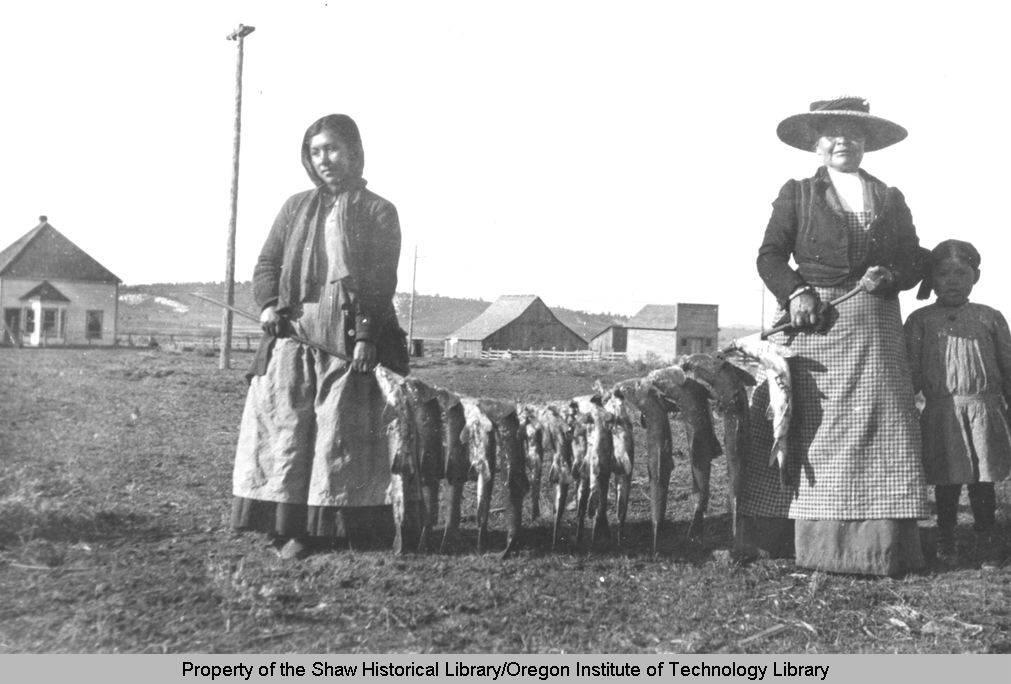

For thousands of years, the Klamath, Modoc, and Yahooksin-Pauite people waited through deadly, food-scarce winters in Southern Oregon for a sure sign of spring returning. When the c'waam and koptu, fish also called Lost River Suckers (Deltistes luxatus) and Shortnose Suckers (Chasmistes brevirostris), came back to spawn on the banks of the Sprague River, the tribes knew warmer weather was coming and the hunger would end. The survival of the Klamath Tribes was so intertwined with suckers that their creator, Gmok'amp'c, proclaimed that as long as the c'waam and koptu remained, their people would continue to exist.

These sacred fish were a vital food source for the Klamath Tribes and later European settlers for generations. Yet today, suckers are at risk for extinction. In 1988, the Lost River and Shortnose suckers were listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). So few suckers exist that members of the Klamath Tribes often struggle to find them to celebrate the arrival of spring.

How did we go from rivers and lakes brimming with these fish to so few remaining?

Informing the balance of water for people and fish

Straddling the border between southern Oregon and Northern California, the Klamath River Basin is an upside-down watershed. Typical watersheds have sparsely inhabited, mountainous streams converging into larger rivers, and then broad deltas on coastal plains that are often densely populated. The Klamath River Basin is inverted. The headwaters of the Klamath quickly congregate into large lakes and seasonal wetlands in wide flatlands tucked among the mountains: a haven for farming and ranching communities. From there, the Klamath River rapidly narrows and winds through rugged terrain all the way to the coast where it spills into the Pacific Ocean.

By law, water allocation decisions must balance the needs of agriculture, consumption, tribal treaty rights to hunt and fish, and plants and animals listed under the Endangered Species Act. This is particularly complicated in the Klamath Basin. Water demands for agriculture and ESA-listed suckers and salmon have come face-to-face with an in increase in the frequency and severity of droughts.

This is where US Geological Survey’s Western Fisheries Research Center (WFRC) comes into play. Research performed by WFRC scientists is crucial for water management and sucker recovery. As resource managers work to provide water security for inhabitants of the basin while continuing the restoration of critical watersheds, they rely on continuous data collection, analysis and development of tools connecting habitat, flows, water quality, and ecosystem effects to fish outcomes. Further, managers look to WFRC science to help parse the influence of water management relative to other factors that may be affecting sucker survival.

After hours on the river and around 20 nets turning up empty of juvenile suckers, we steer the boat back towards the marshlands near our truck. Last few nets left. We drag in the net as large American White Pelicans (Pelecanus erythrorhynchos) swarm above us. They, too, are interested in our catch.

Then we see it. One. One tiny juvenile sucker, not longer than the length of a hand lay in the net amongst all of the other fish. We fill up a bucket of water and begin data collection at last.

What we know about Klamath suckers

Through decades of research, scientists of the USGS Western Fisheries Research Center have determined that, over the last 30 years, something has prevented young suckers from reaching adulthood. The death of juvenile fish has left the c’waam (Lost River Suckers) and koptu (Shortnose Suckers) populations aging andnow approaching their maximum life span of 30-40 years old.

Further, in the past 25 years, the recruitment of new fish into the adult populations has never exceeded the number of adults that have perished in Upper Klamath Lake. The number of adult endangered Lost River and Shortnose Suckers in Upper Klamath Lake declined by roughly 87% between 2001 and 2023. Another population of Lost River Suckers reside in Clear Lake, California, and their persistence also is in question. These populations are the last of their kind.

How do scientists learn about these sacred fish when they live underwater in a world so different from our own?

Since the late 1990’s, the WFRC has used the same technology to monitor suckers you use to pay highway tolls with a pass on your windshield, without stopping your car. Passive Integrated Transponders, or PIT tags, are tracking tags that do not require power, instead using a microchip activated when it passes close to a special antenna. The antenna connects to a computer that records the identity of the tag and the time that it passed.

To track suckers, scientists inject PIT tags into juveniles in their first year and, separately, in adults. As the fish pass by special signal receivers placed throughout the habitat, the PIT tags report the fish’s presence at the site. When scientists deploy an array of receivers, they can track fish movement, count how many fish survive over time, and evaluate how fish use their habitat. Tracking fish populations using PIT tags helps scientists determine which factors affect fish survival and to what degree – informing answers to questions about how things like physical habitat, disease, predation, and water quality and quantity affect these fish.

With this information, WFRC staff have found most Lost River and Short Nosed suckers are dying before they reach age two. But why?

Ecosystem Challenges

Since 2009, the WFRC has partnered with Real Time Research to study bird predation of suckers. Scientists scan large nesting sites of fish-eating (piscivorous) birds, looking for PIT tags from juvenile and adult suckers that have been eaten by the birds. To date, the research suggests that predation by waterbirds, like American White Pelicans (Pelecanus erythrorhynchos) and Double-crested Cormorants (Nannopterum auritum), has been a substantial source of sucker deaths in some years, but unlikely the primary source of the decline in sucker populations.

Scientists and managers have questioned whether water levels within Upper Klamath Lake induce sucker mortality. As part of water allocation management for the basin, water level is controlled by a dam at the lake’s outlet. Researchers from WFRC looked at 22 years of data to investigate the effect of water level – the height of the lake above sea level - on sucker populations. Results indicated that the lake surface elevations in the period studied were unlikely to drive adult fish die offs in the lake. However, low lake levels in the spring are known to diminish lake-spawning habitat and can reduce potential habitat for multiple life stages of suckers.

Water quality may impact fish populations. For example, agricultural practices of allowing cattle near unfenced tributaries, return flows from irrigated land, and natural erosion from soils high in phosphorus can increase the amount of nutrients moving into the water of Upper Klamath Lake. Eutrophication then occurs as excess nutrients cause disruptive algal blooms. Certain algae can kill fish outright. Alternatively, when algae die in large quantities, microbes eating the dead algae consume oxygen in the water, leading to water with low oxygen levels (hypoxia) that can kill fish and other aquatic life. WFRC studies have found juvenile suckers are generally quite hardy to poor water quality (low dissolved oxygen, higher pH, and/or harmful algae) alone; however, could be a compounding factor if other impacts are stressing the fish. More research is required to determine if harmful algae are altering the food web, affecting food availability for suckers.

Disease Impacts

Disease may also play a role in the death of juvenile Lost River and Shortnose suckers. One parasite, the worm-like trematode called an eye fluke, is present in large numbers in the Upper Klamath Lake ecosystem. The eye fluke borrows through muscle and eye tissue which can mutilate fish--making them easier prey--or outright kill the fish when they infect in large numbers. Little is known about how deadly these parasites may be to juvenile suckers.

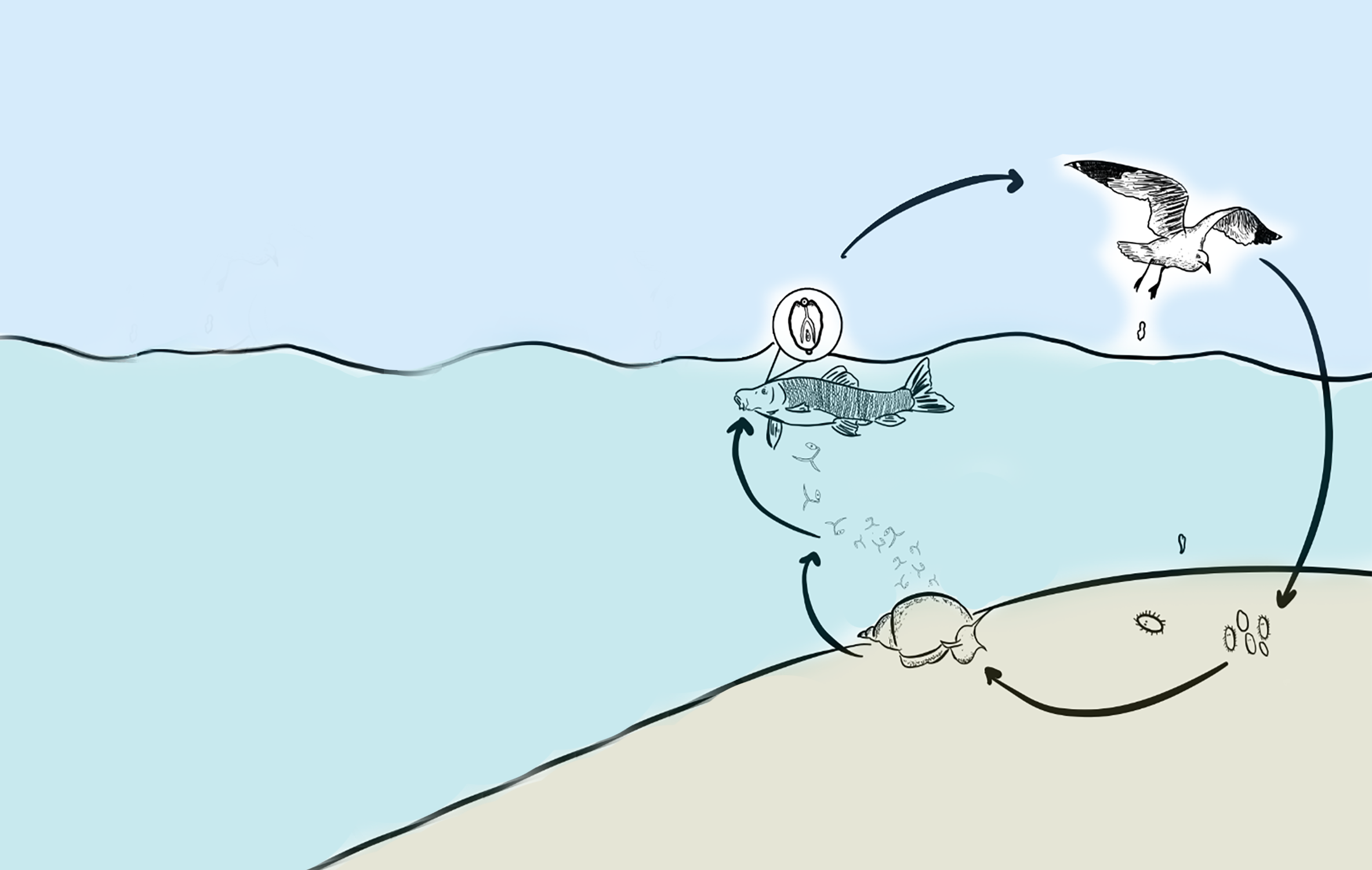

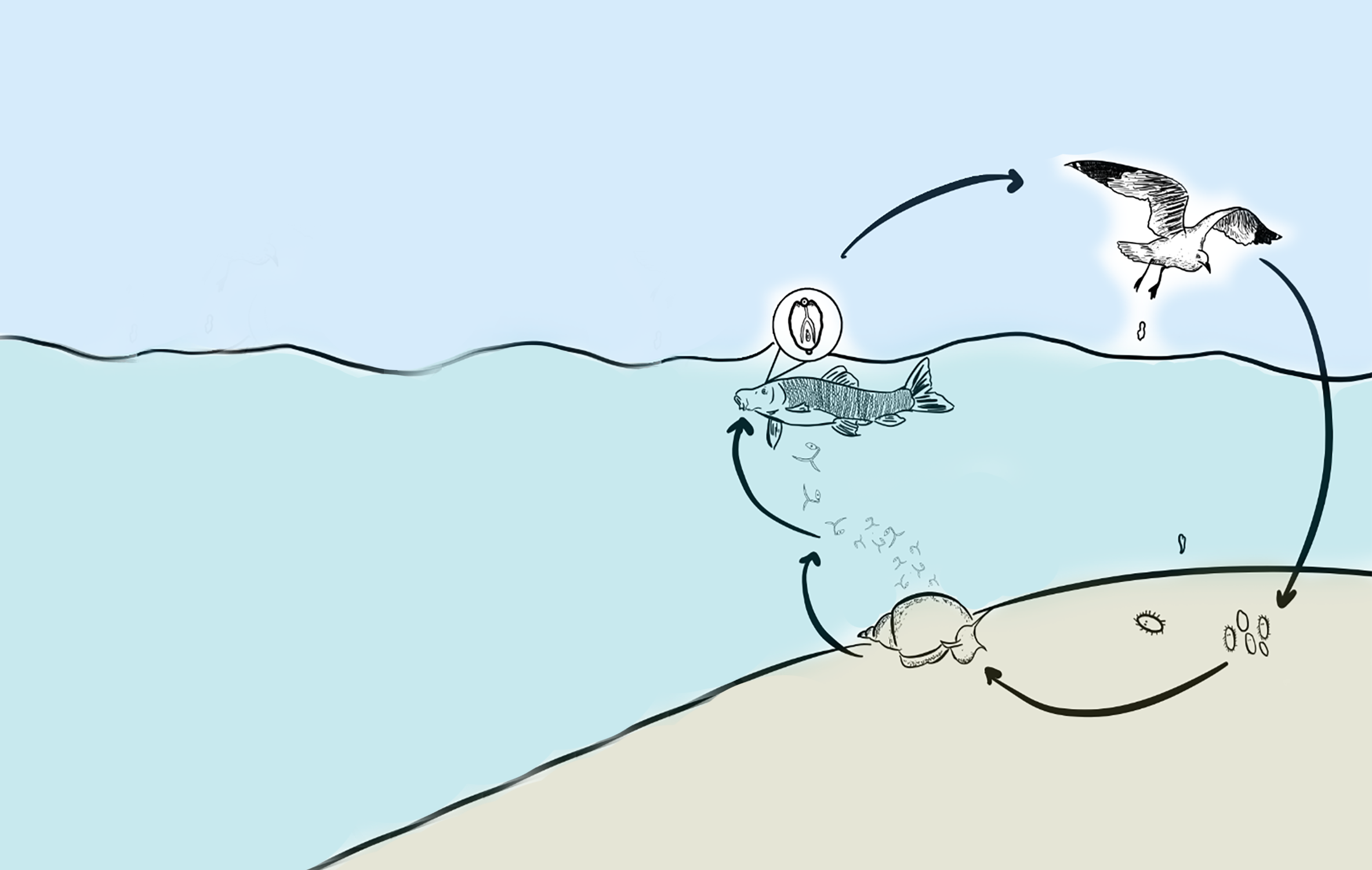

Upper Klamath Lake is home to large colonies of birds and an abundance of snails and fish, making it a haven for trematodes who are reliant on all three for their life cycle. Birds host adult flukes in their intestines. Parasite eggs are shed when birds poop, and after hatching, free-swimming parasites go on to infect snails. Following a period of incubation, snails will shed large numbers of free-swimming parasites (cercariae), which then infect fish. Infected fish develop a variety of ailments depending on the fluke species, such as neurological signs, impaired vision, and muscle damage. As these fish become easier prey for water-faring birds the parasite completes its life cycle by moving from fish back to birds. Evolutionary selection has favored parasites that can increase chances of a bird eating their fish host, leading to this suite of ailments in the fish.

WFRC fish health scientists are currently investigating the abundance of eye flukes as well as their ability to injure or outright kill suckers. Surrogate fish species are collected from Upper Klamath Lake as well as thousands of snails to describe the presence of eye flukes in the water body. Experimental work is also being done in WFRC’s Seattle laboratory to understand what levels of infection (i.e., number of eye flukes) lead to poor swimming performance, becoming an easier target for fish-eating birds, or outright death. These two pieces of key information can be used to estimate the relative impact of eye flukes on juvenile Lost River and Shortnose sucker survival.

If eye flukes to appear to play a substantial role in juvenile sucker survival, WFRC scientists will need to evaluate what environmental factors may be making the flukes more prevalent and intense. Hypotheses may include warmer and/or more nutrient-rich waters, or a greater abundance of birds, snails or other fish species. With so much interconnectivity, it is no wonder that finding the cause of juvenile sucker mortality is so complex! Ultimately, determining the link between environmental changes and the prevalence and intensity of eye flukes can guide which management actions will have the greatest impact.

Where do we go from here?

Lost River and Shortnose suckers are on the verge of extinction in Upper Klamath Lake. Age data indicate that almost all adult suckers remaining in the lake spawning populations were hatched in the early 1990s. Most individuals are approaching their maximum life span, and for the past 22 years the recruitment of new fish into the adult populations has never exceeded mortality losses.

In addition to continuing the work described above, WFRC plans to:

- Implant acoustic tags in suckers to refine our understanding of their movement and survival throughout the lake. Acoustic telemetry provides larger, more refined spatial coverage compared to tag readings at designated PIT tag gates.

- Incorporate fish-eating bird tracking across the Upper Klamath River Basin (with the help of USGS Western Ecological Research Center) to further refine our understanding of bird predation on suckers. While not the primary source of juvenile mortality, actions to avoid predation my help improve Sucker survival.

- Help US Fish and Wildlife Service and Klamath Tribes managers determine the best size and age to release suckers reared in hatchery programs intended to boost sucker populations.

- Evaluate juvenile sucker populations int Barkley Springs (a hydrologically connected pond, a.k.a. Hagelstein Pond, to Upper Klamath Lake)—where juveniles survive to adulthood—and compare to the Upper Klamath Lake populations

- Continue to collaboratively monitor sucker, salmon and other fish populations and support data sharing throughout the basin via the Klamath Basin Fisheries Collaborative with Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission, US Fish and Wildlife Service and others.

We are determined to provide the science that will continue to guide water management and ultimately recover these native fish.

Partners:

The Bureau of Reclamation

US Fish and Wildlife Service

The Klamath Tribes

Klamath Basin Fisheries Collaborative

Real Time Research

Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission

USGS Western Ecological Research Center

Growth, survival, and cohort formation of juvenile Lost River (Deltistes luxatus) and shortnose suckers (Chasmistes brevirostris) in Upper Klamath Lake, Oregon, and Clear Lake Reservoir, California—2021–22 monitoring report Growth, survival, and cohort formation of juvenile Lost River (Deltistes luxatus) and shortnose suckers (Chasmistes brevirostris) in Upper Klamath Lake, Oregon, and Clear Lake Reservoir, California—2021–22 monitoring report

Does release size into net-pens affect survival of captively reared juvenile endangered suckers in Upper Klamath Lake? Does release size into net-pens affect survival of captively reared juvenile endangered suckers in Upper Klamath Lake?

Endangered Klamath suckers Endangered Klamath suckers

Validating a non-lethal method of aging endangered juvenile Lost River and Shortnose Suckers Validating a non-lethal method of aging endangered juvenile Lost River and Shortnose Suckers

Water and endangered fish in the Klamath River Basin: Do Upper Klamath Lake surface elevation and water quality affect adult Lost River and Shortnose Sucker survival? Water and endangered fish in the Klamath River Basin: Do Upper Klamath Lake surface elevation and water quality affect adult Lost River and Shortnose Sucker survival?

USGS and its partners are working tirelessly to monitor suckers and understand why they are disappearing from lakes and streams in the Klamath River Basin

Its early morning as we pass a green expanse of farmland and pull into a parking lot with a boat ramp sloping into the massive waters of Upper Klamath Lake. Paving machines drone next to us, widening the road winding along the lake shore. A thick haze of yellow-brown wildfire smoke hangs in the air, obscuring faint outlines of the high peaks surrounding Crater Lake across the water. A swarm of midges and sea of algae greet us as we load our boat. We pack up, leave shore, and head toward our first target—a set of trap nets--with tempered hopes of finding something exceedingly rare: evidence of surviving juvenile suckers.

WFRC scientists are working tirelessly to identify the factors driving the loss of juvenile suckers. Though the problem is complex, our researchers have plans to continue to home in on why juvenile suckers are dying in such large numbers.

A sign of life and livelihood

For thousands of years, the Klamath, Modoc, and Yahooksin-Pauite people waited through deadly, food-scarce winters in Southern Oregon for a sure sign of spring returning. When the c'waam and koptu, fish also called Lost River Suckers (Deltistes luxatus) and Shortnose Suckers (Chasmistes brevirostris), came back to spawn on the banks of the Sprague River, the tribes knew warmer weather was coming and the hunger would end. The survival of the Klamath Tribes was so intertwined with suckers that their creator, Gmok'amp'c, proclaimed that as long as the c'waam and koptu remained, their people would continue to exist.

These sacred fish were a vital food source for the Klamath Tribes and later European settlers for generations. Yet today, suckers are at risk for extinction. In 1988, the Lost River and Shortnose suckers were listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). So few suckers exist that members of the Klamath Tribes often struggle to find them to celebrate the arrival of spring.

How did we go from rivers and lakes brimming with these fish to so few remaining?

Informing the balance of water for people and fish

Straddling the border between southern Oregon and Northern California, the Klamath River Basin is an upside-down watershed. Typical watersheds have sparsely inhabited, mountainous streams converging into larger rivers, and then broad deltas on coastal plains that are often densely populated. The Klamath River Basin is inverted. The headwaters of the Klamath quickly congregate into large lakes and seasonal wetlands in wide flatlands tucked among the mountains: a haven for farming and ranching communities. From there, the Klamath River rapidly narrows and winds through rugged terrain all the way to the coast where it spills into the Pacific Ocean.

By law, water allocation decisions must balance the needs of agriculture, consumption, tribal treaty rights to hunt and fish, and plants and animals listed under the Endangered Species Act. This is particularly complicated in the Klamath Basin. Water demands for agriculture and ESA-listed suckers and salmon have come face-to-face with an in increase in the frequency and severity of droughts.

This is where US Geological Survey’s Western Fisheries Research Center (WFRC) comes into play. Research performed by WFRC scientists is crucial for water management and sucker recovery. As resource managers work to provide water security for inhabitants of the basin while continuing the restoration of critical watersheds, they rely on continuous data collection, analysis and development of tools connecting habitat, flows, water quality, and ecosystem effects to fish outcomes. Further, managers look to WFRC science to help parse the influence of water management relative to other factors that may be affecting sucker survival.

After hours on the river and around 20 nets turning up empty of juvenile suckers, we steer the boat back towards the marshlands near our truck. Last few nets left. We drag in the net as large American White Pelicans (Pelecanus erythrorhynchos) swarm above us. They, too, are interested in our catch.

Then we see it. One. One tiny juvenile sucker, not longer than the length of a hand lay in the net amongst all of the other fish. We fill up a bucket of water and begin data collection at last.

What we know about Klamath suckers

Through decades of research, scientists of the USGS Western Fisheries Research Center have determined that, over the last 30 years, something has prevented young suckers from reaching adulthood. The death of juvenile fish has left the c’waam (Lost River Suckers) and koptu (Shortnose Suckers) populations aging andnow approaching their maximum life span of 30-40 years old.

Further, in the past 25 years, the recruitment of new fish into the adult populations has never exceeded the number of adults that have perished in Upper Klamath Lake. The number of adult endangered Lost River and Shortnose Suckers in Upper Klamath Lake declined by roughly 87% between 2001 and 2023. Another population of Lost River Suckers reside in Clear Lake, California, and their persistence also is in question. These populations are the last of their kind.

How do scientists learn about these sacred fish when they live underwater in a world so different from our own?

Since the late 1990’s, the WFRC has used the same technology to monitor suckers you use to pay highway tolls with a pass on your windshield, without stopping your car. Passive Integrated Transponders, or PIT tags, are tracking tags that do not require power, instead using a microchip activated when it passes close to a special antenna. The antenna connects to a computer that records the identity of the tag and the time that it passed.

To track suckers, scientists inject PIT tags into juveniles in their first year and, separately, in adults. As the fish pass by special signal receivers placed throughout the habitat, the PIT tags report the fish’s presence at the site. When scientists deploy an array of receivers, they can track fish movement, count how many fish survive over time, and evaluate how fish use their habitat. Tracking fish populations using PIT tags helps scientists determine which factors affect fish survival and to what degree – informing answers to questions about how things like physical habitat, disease, predation, and water quality and quantity affect these fish.

With this information, WFRC staff have found most Lost River and Short Nosed suckers are dying before they reach age two. But why?

Ecosystem Challenges

Since 2009, the WFRC has partnered with Real Time Research to study bird predation of suckers. Scientists scan large nesting sites of fish-eating (piscivorous) birds, looking for PIT tags from juvenile and adult suckers that have been eaten by the birds. To date, the research suggests that predation by waterbirds, like American White Pelicans (Pelecanus erythrorhynchos) and Double-crested Cormorants (Nannopterum auritum), has been a substantial source of sucker deaths in some years, but unlikely the primary source of the decline in sucker populations.

Scientists and managers have questioned whether water levels within Upper Klamath Lake induce sucker mortality. As part of water allocation management for the basin, water level is controlled by a dam at the lake’s outlet. Researchers from WFRC looked at 22 years of data to investigate the effect of water level – the height of the lake above sea level - on sucker populations. Results indicated that the lake surface elevations in the period studied were unlikely to drive adult fish die offs in the lake. However, low lake levels in the spring are known to diminish lake-spawning habitat and can reduce potential habitat for multiple life stages of suckers.

Water quality may impact fish populations. For example, agricultural practices of allowing cattle near unfenced tributaries, return flows from irrigated land, and natural erosion from soils high in phosphorus can increase the amount of nutrients moving into the water of Upper Klamath Lake. Eutrophication then occurs as excess nutrients cause disruptive algal blooms. Certain algae can kill fish outright. Alternatively, when algae die in large quantities, microbes eating the dead algae consume oxygen in the water, leading to water with low oxygen levels (hypoxia) that can kill fish and other aquatic life. WFRC studies have found juvenile suckers are generally quite hardy to poor water quality (low dissolved oxygen, higher pH, and/or harmful algae) alone; however, could be a compounding factor if other impacts are stressing the fish. More research is required to determine if harmful algae are altering the food web, affecting food availability for suckers.

Disease Impacts

Disease may also play a role in the death of juvenile Lost River and Shortnose suckers. One parasite, the worm-like trematode called an eye fluke, is present in large numbers in the Upper Klamath Lake ecosystem. The eye fluke borrows through muscle and eye tissue which can mutilate fish--making them easier prey--or outright kill the fish when they infect in large numbers. Little is known about how deadly these parasites may be to juvenile suckers.

Upper Klamath Lake is home to large colonies of birds and an abundance of snails and fish, making it a haven for trematodes who are reliant on all three for their life cycle. Birds host adult flukes in their intestines. Parasite eggs are shed when birds poop, and after hatching, free-swimming parasites go on to infect snails. Following a period of incubation, snails will shed large numbers of free-swimming parasites (cercariae), which then infect fish. Infected fish develop a variety of ailments depending on the fluke species, such as neurological signs, impaired vision, and muscle damage. As these fish become easier prey for water-faring birds the parasite completes its life cycle by moving from fish back to birds. Evolutionary selection has favored parasites that can increase chances of a bird eating their fish host, leading to this suite of ailments in the fish.

WFRC fish health scientists are currently investigating the abundance of eye flukes as well as their ability to injure or outright kill suckers. Surrogate fish species are collected from Upper Klamath Lake as well as thousands of snails to describe the presence of eye flukes in the water body. Experimental work is also being done in WFRC’s Seattle laboratory to understand what levels of infection (i.e., number of eye flukes) lead to poor swimming performance, becoming an easier target for fish-eating birds, or outright death. These two pieces of key information can be used to estimate the relative impact of eye flukes on juvenile Lost River and Shortnose sucker survival.

If eye flukes to appear to play a substantial role in juvenile sucker survival, WFRC scientists will need to evaluate what environmental factors may be making the flukes more prevalent and intense. Hypotheses may include warmer and/or more nutrient-rich waters, or a greater abundance of birds, snails or other fish species. With so much interconnectivity, it is no wonder that finding the cause of juvenile sucker mortality is so complex! Ultimately, determining the link between environmental changes and the prevalence and intensity of eye flukes can guide which management actions will have the greatest impact.

Where do we go from here?

Lost River and Shortnose suckers are on the verge of extinction in Upper Klamath Lake. Age data indicate that almost all adult suckers remaining in the lake spawning populations were hatched in the early 1990s. Most individuals are approaching their maximum life span, and for the past 22 years the recruitment of new fish into the adult populations has never exceeded mortality losses.

In addition to continuing the work described above, WFRC plans to:

- Implant acoustic tags in suckers to refine our understanding of their movement and survival throughout the lake. Acoustic telemetry provides larger, more refined spatial coverage compared to tag readings at designated PIT tag gates.

- Incorporate fish-eating bird tracking across the Upper Klamath River Basin (with the help of USGS Western Ecological Research Center) to further refine our understanding of bird predation on suckers. While not the primary source of juvenile mortality, actions to avoid predation my help improve Sucker survival.

- Help US Fish and Wildlife Service and Klamath Tribes managers determine the best size and age to release suckers reared in hatchery programs intended to boost sucker populations.

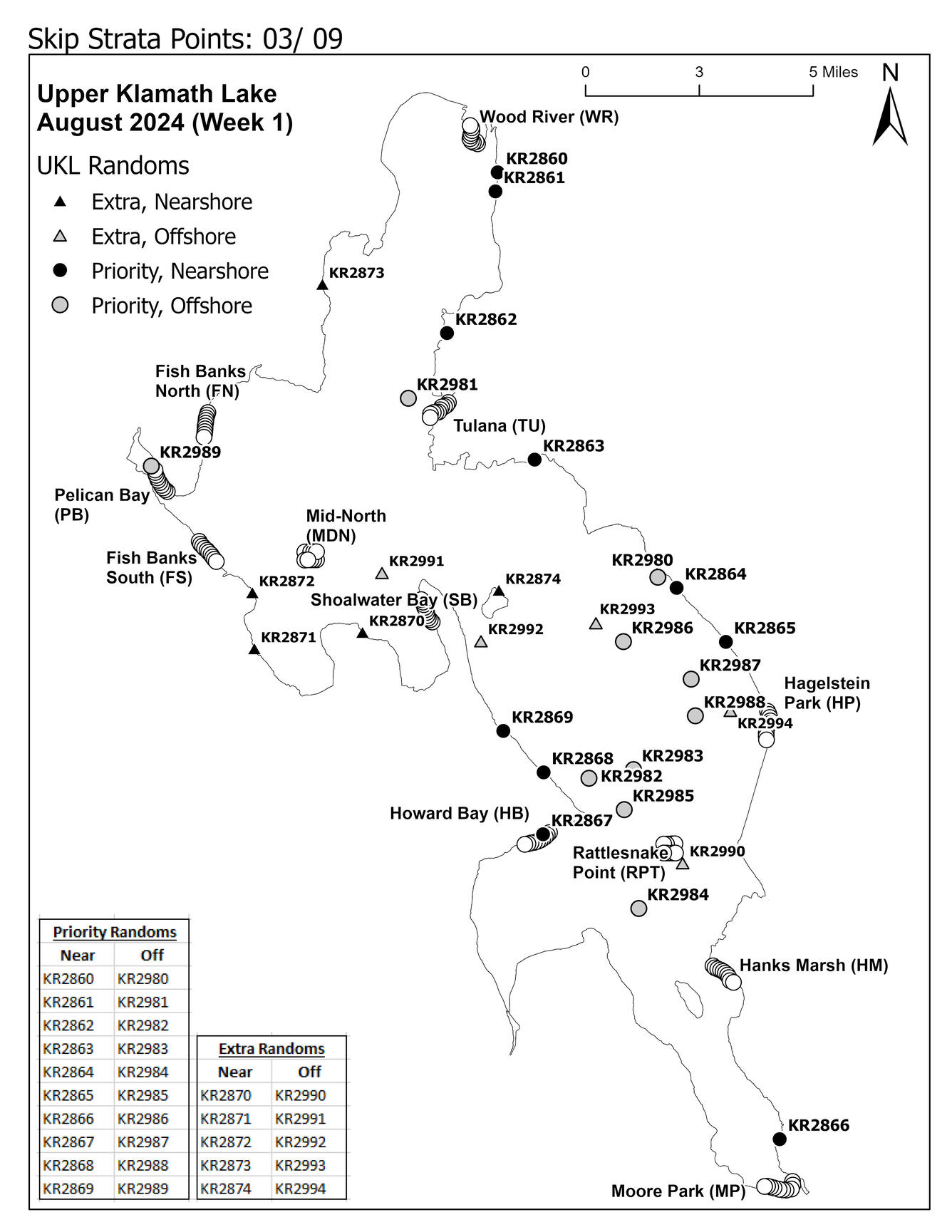

- Evaluate juvenile sucker populations int Barkley Springs (a hydrologically connected pond, a.k.a. Hagelstein Pond, to Upper Klamath Lake)—where juveniles survive to adulthood—and compare to the Upper Klamath Lake populations

- Continue to collaboratively monitor sucker, salmon and other fish populations and support data sharing throughout the basin via the Klamath Basin Fisheries Collaborative with Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission, US Fish and Wildlife Service and others.

We are determined to provide the science that will continue to guide water management and ultimately recover these native fish.

Partners:

The Bureau of Reclamation

US Fish and Wildlife Service

The Klamath Tribes

Klamath Basin Fisheries Collaborative

Real Time Research

Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission

USGS Western Ecological Research Center