Like women researchers in other organizations and other scientific disciplines, women PI’s at USGS must manage unique career challenges, while pursuing their research questions and making an impact on our world.

True to the USGS tradition, scientist Amy Vandergast makes maps. But her maps are not ones of geological formations -- they are snapshots in time and space of the evolutionary history and potential of animals.

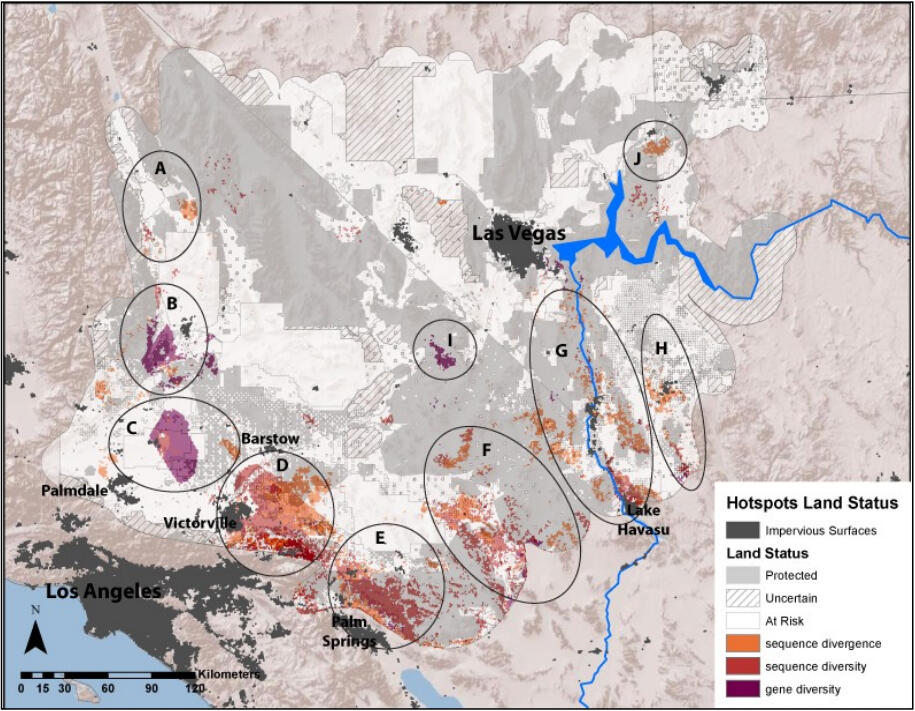

“These purple, red, and orange zones here are where animal populations in the Mojave Desert show the most genetic diversity,” Vandergast explains, pointing to a freckled map of Southern California. “It’s one way of visualizing which regions you might protect if you want to benefit the most number of wildlife species.”

High genetic diversity within a population of animals is a good thing. It can reflect areas where populations are large, or where individuals are able to move across different habitats, mate, and mix genes. Genetic diversity is the raw material for evolution, and protecting areas with high diversity -- and movement corridors to and from these regions -- may help maintain a species’ ability to adapt to changing conditions.

So, these maps are a pretty convenient way of identifying which landscapes should receive more protection and less human disturbance -- and these maps were made possible thanks to a tool Vandergast helped create.

Dr. Vandergast is one of the 22 principle investigators at the USGS Western Ecological Research Center -- nine of whom are women. The principle investigator or “PI” title reflects her rank as a supervisory scientist within USGS -- an experienced researcher who leads their own research team and is evaluated on the scientific innovations and scholarly findings they produce. WERC PI’s must be able to bridge multiple disciplines of science and harness them towards creative solutions that tackle some of the pressing ecological questions facing us today.

Take, for example, this evolutionary hotspots map.

Several years ago, Southern California resource agencies like California State Parks and San Diego Association of Governments needed a way to assess the population genetics of wildlife species on their landscape, so they can design land conservation efforts around areas and corridors that promote healthy gene flow for wildlife species.

Vandergast’s expertise is in wildlife population genetics, assessing where populations might be diverging into new lineages, or where populations are becoming isolated and inbred -- be it lizards or snakes or birds or spiders. Vandergast and her team had the genetics data from hundreds of specimens collected from different locations in Southern California, and like crime scene labs and paternity testing services, they already knew how to compare one individual animal’s DNA against other individual samples.

But now, they had to somehow compare all these DNA signatures across an entire landscape -- displaying these genetic differences across geographical space.

So Vandergast, WERC biologist Stacie Hathaway and GIS specialists Bill Perry and Robert Lugo worked together to create the “Genetic Landscapes GIS Toolbox” in 2010, an ArcGIS model that allows any researcher to chart out their wildlife genetics data into ready-to-use maps. Natural resource managers then can overlay this map against maps of proposed land development or land conservation, and see whether these land-use proposals mesh with or interfere with wildlife population health.

The tool was a success for Southern California managers and downloaded by hundreds of wildlife researchers across the country. Moreover, the landscape genetics approach is being adapted to help solve one of the most complex environmental issues in the U.S. West: how to reconcile solar energy development plans with wildlife conservation plans in the Mojave Desert.

Federal and state agencies and conservation and industry stakeholders are seeking new tools and data to guide their decisions, and Vandergast’s maps are now a part of that tool box. Her research comparing energy project footprints with evolutionary hotspots in the Mojave and Sonoran deserts is making sure that tiny genes processed at the lab bench are informing actions that will shape the future of entire ecosystems.

“Being a research scientist with USGS is always interesting and challenging, and there are always so many new projects to take on and new research ideas to test and develop,” says Vandergast. “I am proud of my accomplishments and that my work supports conservation efforts.”

Desert energy is a recent issue, but women PI’s at WERC have long contributed high-impact research to the field of ecology. Elsewhere in the Mojave Desert, Dr. Kristin Berry has studied the diseases and environmental factors facing the threatened desert tortoise (Gopherus agassizii) for more than four decades, and she is one of the most respected herpetologists in the Southwest. Also studying the desert landscapes is Dr. Lesley DeFalco, who investigates how to restore native plant species and dwindling desert habitat, and Kathy Longshore, who tracks how desert animals like bighorn sheep and golden eagles find food and water and avoid human contact.

Traveling between San Diego and Mexico, Dr. Barbara Kus monitors how endangered songbirds survive annual migrations and fire-razed habitat. In the Channel Islands, Dr. Kathryn McEachern watches the daily fog for clues to protect rare island plants and to understand coastal California’s water cycles. Using GPS collars and hidden cameras, Dr. Erin Boydston uncovers how bobcats and cougars navigate the urban maze of greater Los Angeles. And all along the California, Oregon and Washington coast, Dr. Karen Thorne is establishing climate change observatories to analyze and forecast how sea level rise will alter the existence of our tidal wetlands.

And those are just the PI’s, not yet mentioning the scores of other WERC women scientists throughout California and Nevada who are surveying forests, analyzing oil spill impacts, sharpening statistical models, sampling salt marshes, or traversing the sagebrush steppes -- to list only a few examples.

Like women researchers in other organizations and other scientific disciplines, women PI’s at USGS must manage unique career challenges, while pursuing their research questions and making an impact on our world. WERC PI’s like Berry and Vandergast actively work with their peers to foster ideas for positive change and to mentor young women scientists.

And of course, as role models, the impact of women scientists extends beyond the workplace.

“My own children are in elementary school, so I mainly interact with young kids,” says Vandergast. “When I talk to their classmates about how my job is to do research to help protect and manage endangered animals and habitats, I also like to mention the simple things that they can do every day to help in conservation efforts, like saving water and reusing and recycling -- even if they are more impressed about the fact that I work on insects and spiders!”

-- Ben Young Landis