Northern Spotted Owl Still Fights for Survival

Three studies highlight how the interactions between northern spotted owl and the invasive barred owl are intertwined.

You don’t have to drive far into the forests of the Pacific Northwest to hear the distinctive hooting of the invasive barred owl high in the treetops. In fact, you can find them in the neighborhoods of cities like Portland, Oregon, where you might glimpse one perched above on a walk around the block or, you might be surprised when one swoops down to chase you away from its territory. The barred owl is an invasive species in these parts that competes with and threatens the existence of the native northern spotted owl.

USGS and partner scientists in recent months published the results of three studies about the current status of the threatened northern spotted owl populations, and the effects of barred owls and barred owl removal on northern spotted owl populations. The combined results show that even while forest management policies and practices maintained northern spotted owl habitat across their range, barred owls pose a very serious threat to remaining populations of northern spotted owl.

The northern spotted owl, a federally listed species, is an old-growth forest obligate, which means it is tied to mature forests with large trees. The owl is at the center of controversial forest management issues in the Pacific Northwest because of immediate threats to its existence, which resulted in mandated changes to forestry practices.

The barred owl is an apex predator and a fiercely territorial invader from eastern North America. Unlike the northern spotted owl, barred owls can thrive in a wider variety of forest conditions and they aggressively push northern spotted owls out of their established territories. Invasive barred owls will eat anything they can catch, having what is called a “generalist” appetite. Their sheer numbers and generalist appetite threaten not only the northern spotted owl, but other native wildlife throughout the region. The first records of barred owls in the U.S. Pacific Northwest date back to the early 1970s. Barred owls were historically found through most of eastern North America. They spread west during the 1900s and today completely overlap the range of the northern spotted owl.

Long-term monitoring of northern spotted owl reveals trends

The following three studies are the most recent long-term analyses produced by, or in partnership with, the Northwest Forest Plan Interagency Monitoring Program. The Northwest Forest Plan governs land use and management of federal forest lands in the Pacific Northwest within the range of the northern spotted owl – roughly 10 million hectares, or almost 25 million acres of forested land within western Oregon and Washington and northern California. The three studies do not include data from the large wildfires that burned through Pacific Northwest old-growth forests since 2017.

Study #1: Northern spotted owl in decline

The first of three studies looked at northern spotted owl population data collected over 26 years across this owls’ geographic range, in the US, and assessed vital rates, such as reproduction and survival, and population trends. “One component of the Northwest Forest Plan required long-term monitoring of northern spotted owl populations,” said Alan Franklin, a research scientist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Wildlife Research Center with the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service and lead author of the first study. “Monitoring of northern spotted owls was established as early as 1985. Additional and subsequent studies were alike in that all used similar field methods. This allowed us to complete a meta-analysis of all the different northern spotted owl studies over the years.”

Franklin and his colleagues found that northern spotted owl populations have experienced significant yearly declines, translating to a 65-85% population decrease on many of the study areas between 1995 and 2017. Barred owl presence on northern spotted owl territories was the primary factor negatively affecting apparent survival, recruitment, and ultimately, rates of population change. Without removal or reduction of barred owl populations, it’s likely northern spotted owls will become locally extinct from portions of their range. The species would possibly linger on as small populations in other areas until those populations are eliminated by catastrophic events, such as wildfire, resulting in its extinction.

Study #2: Northern spotted owls are on the move

The second study looked at northern spotted owl breeding dispersal, or their movement from one breeding territory to another. The consequences of altered breeding dispersal on northern spotted owls are unknown but could affect population dynamics of this threatened species. Federal and university researchers looked at how barred owls, forest disturbance, and social and individual conditions affect decisions made by individual northern spotted owls to move to a new breeding territory or not.

Using data collected from 4,118 northern spotted owls in Oregon and Washington from 1990 to 2017, the researchers found the percent of northern spotted owls dispersing from their territories each year has increased by more than 17% in recent times. The increases coincided with a rapid increase in numbers of invasive barred owls as they quickly colonized Pacific Northwest forests and displaced northern spotted owls from their preferred breeding sites. Single spotted owls and those that had also dispersed the previous year were more likely to move. Northern spotted owls were less likely to leave high-quality territories with historically high levels of successful reproduction by spotted owls.

“Our study further shows that increasing rates of breeding dispersal associated with population declines contribute to population instability and vulnerability of northern spotted owls to extinction,” said Julianna Jenkins, U.S. Forest Service (USFS) wildlife biologist and lead author of the study.

Study #3: Barred owl removal works

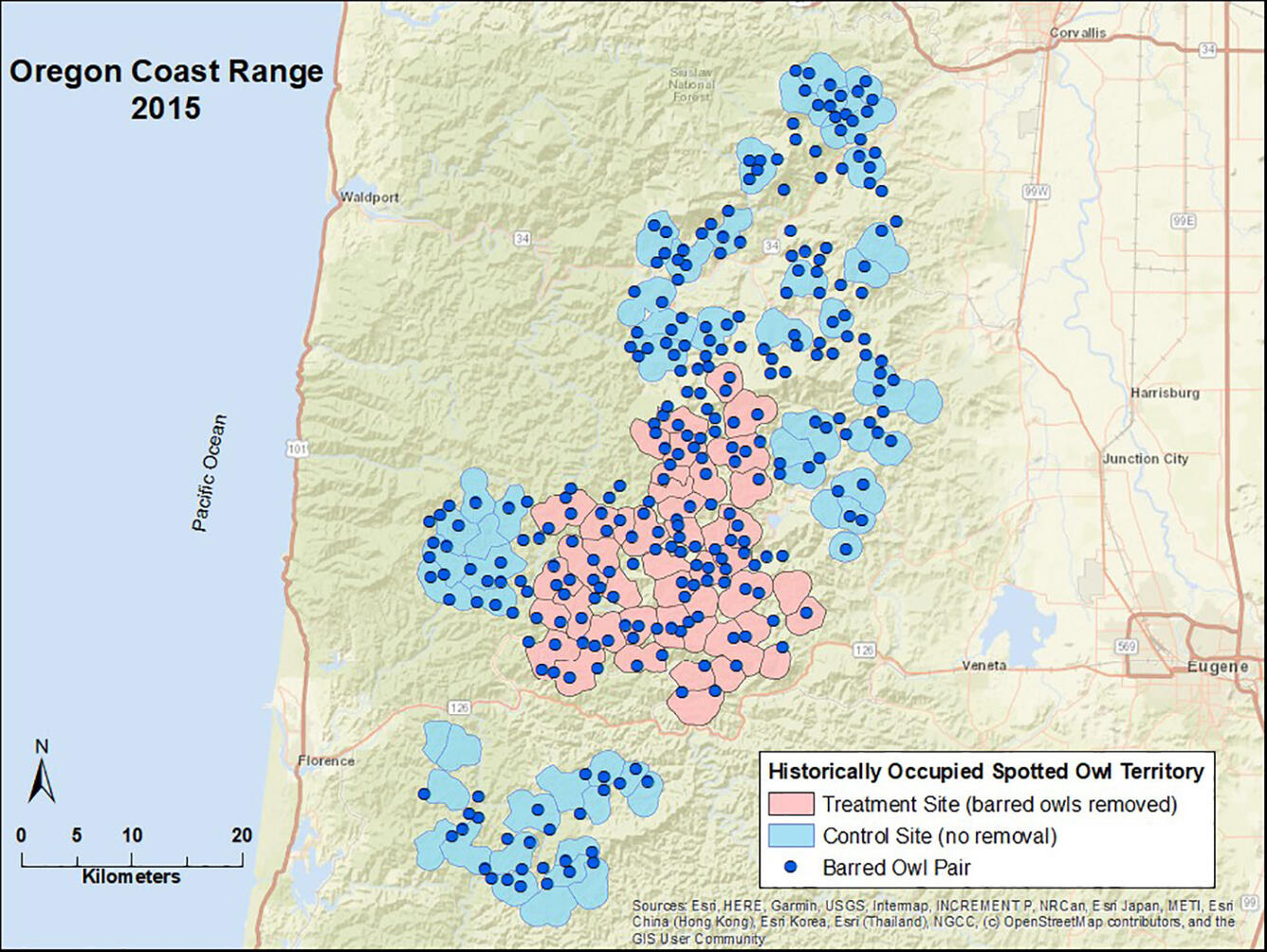

The third study is the barred owl removal experiment, led by David Wiens, USGS research wildlife biologist. Wiens and his colleagues designed a large-scale removal experiment in Washington, Oregon and California to investigate the response of the northern spotted owl to removal of the barred owl. “Invader removal is a common management response, but the use of long-term field experiments to test the effectiveness of removals in benefitting impacted native species is rare,” said Wiens. “This study is the largest field experiment ever conducted on the demographic consequences of invasive competition between predatory birds.”

The experiment used data from the long-term Northwest Forest Plan Interagency Monitoring Program (2002-2019), a similar barred owl removal effort on Green Diamond Resource Company lands in northern California (2009-2014), and the Barred Owl Removal Project (2013-2019) to scientifically test the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s (USFWS) plan to recover the northern spotted owl from its status as a Threatened species under the Endangered Species Act. “The USFWS considered multiple approaches to implementing Recovery Action 29 - 'Design and implement large-scale control experiments to assess the effects of barred owl removal on spotted owl site occupancy, reproduction, and survival,' including both non-lethal and lethal removal techniques,” said Robin Bown, USFWS lead for the Barred Owl Project. “The USFWS’s Record of Decision provided the direction for the USGS experimental study.”

Removal of barred owls had a strong, positive effect on the survival of northern spotted owls, stopping their long-term population declines. After removals, northern spotted owl population declines stabilized in areas with removals but continued to decrease sharply in areas without removals. “The results of the study showed that long-term survival of northern spotted owls will depend heavily on reducing the negative impacts of barred owls while simultaneously addressing other threats such as habitat loss,” added Wiens.

“The Northwest Forest Plan has protected significant amounts of the northern spotted owl’s nesting and roosting forests. During the first 25 years the plan has been in place, the amount of this forest on federal lands increased by about 3%. This increase occurred despite losses from wildfire, timber harvest and insect or other causes. Preliminary monitoring data show those gains have been lost owing to three recent large wildfire years — 2017, 2018, and 2020. Each of these years burned more than a million acres and in total, over 4 million acres of forest in the owl’s range,” said Paul Anderson, director of the USFS Pacific Northwest Research Station. “For 2021, we have estimated another million acres have been burned in the owl’s range.”

“Removing one species to save another is a difficult decision and one that the USFWS did not take lightly. These studies and others show that it is very likely the northern spotted owl would go extinct in large portions of its range if the threat from invasive barred owls and management of spotted owl habitat are not addressed simultaneously,” said Bown. “The northern spotted owl is a federally listed threatened species. On behalf of the American people, the Service and other federal agencies have a legal and ethical responsibility to do everything we can, within the confines of our respective authorities and funding, to prevent its extinction and help it recover,” added Paul Henson, State Supervisor of the USFWS Oregon Office.

This work was funded by a partnership between the USFWS, USGS, USFS, Bureau of Indian Affairs, and Bureau of Land Management.

Authors’ institutions in alphabetical order: BLM, Colorado State University, Green Diamond Resource Company, Hoopa Valley Tribe, McDonald Data Sciences, National Park Service, Oregon State University, Raedeke Associates, Simon Fraser University, University of Florida, USDA-APHIS, USFS, USFWS, USGS, Utah State University, Western Ecosystem Technology (WEST), Inc.