The story of the Gallatin Range—magnificent mountains northwest of Yellowstone Caldera

Mountain building occurred all around the Yellowstone region and highlights a tortured geological history of uplift and volcanism. The Gallatin Range, just northeast of Yellowstone Caldera, is an excellent example.

Yellowstone Caldera Chronicles is a weekly column written by scientists and collaborators of the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory. This week's contribution is from Stanley Mordensky, geologist with the U.S. Geological Survey.

The Laramide Orogeny was a mountain-building event that took place roughly 70 to 50 million years ago and raised rocks that were billions of years old into some of the ranges we see today, like the Wind River Range southeast of Yellowstone National Park and the Beartooth Mountains to the north of Yellowstone National Park. The Gallatin Range, along the park’s northwest boundary, is another area of ancient rocks impacted by more recent (in a geological sense) uplift.

The Gallatin Range, named after Albert Gallatin, the U.S. Secretary of the Treasury under Presidents Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, extends 120 km (75 miles) north from Mt. Holmes (which is about 15 km (9 miles) northwest of the Norris Geyser Basin in Yellowstone National Park) to Bozeman Pass on U.S. Interstate 90 between Bozeman and Livingston, MT. The width of the range averages 32 km (20 miles). The Gallatin Range has 10 peaks above 3,000 m (approximately 10,000 ft), with the highest point being Electric Peak at 3,343 m (10,969 ft) in northwest Yellowstone National Park. Curiously, Gallatin Peak is not found in the Gallatin Range, but, instead, in the neighboring Madison Range.

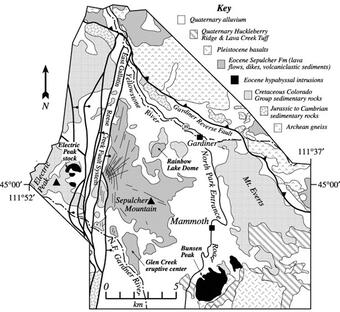

The Gallatin range is an assemblage of old (even by geological standards) metamorphic rock, younger sedimentary layers, and younger still volcanics. The metamorphic rocks are gneisses, which formed under high-temperature and high-pressure conditions at great depth. For example, the gneiss at Gallatin Canyon formed at depths greater than 25 to 30 km (15 to 18 miles) beneath the Earth’s surface at temperatures around 780 °C (1440 °F). These gneisses have ages roughly between 3.6 and 2.7 billion years, meaning that they are around 79% to 59% the entire age of the Earth and more than 4,000 times older than the youngest caldera-forming eruption from the Yellowstone Caldera complex!

In the Gallatin Range, there is a gap in the geologic record from roughly 2.7 billion years ago until about 542 million years ago. This gap coincides with the Great Unconformity, a substantial break in the geologic record described across the world. Then, a shallow inland sea formed in the region around 542 million years ago. As the water levels rose and fell through the Paleozoic (542 to 251 million years ago) and parts of the Mesozoic (251 to 65.5 million years ago) eras, the metamorphic gneisses were overlain with sedimentary deposits that formed limestone, shale, and sandstone.. These sedimentary rocks are roughly 10 times younger than the metamorphic gneisses but still at least 100 times older than the youngest caldera-forming eruption from the Yellowstone volcanic system.

Starting around 160 million years ago, subduction of the oceanic Farallon Plate beneath the North American Plate began deforming and raising parts of western North America. Around 80 million years ago, this deformation began raising the low-lying metamorphic and sedimentary rocks into the Gallatin Range, continuing until roughly 50 million years ago. The latter part of this deformation coincided with the formation of other ranges in the Yellowstone region, like the Wind River Range and the Beartooth Mountains, as well as the eruptions of the Absaroka volcanoes in the northern and eastern regions of Yellowstone.

The Gallatin Range itself experienced some volcanic activity, and the distinction between Gallatin and Absaroka ranges becomes a bit blurred where Absaroka volcanics are found in the Gallatin Range—so much so that the two ranges have been collectively referred to as the Absaroka-Gallatin volcanic province. For example, Sepulcher Mountain, in the northern part of Yellowstone National Park, is generally labeled as a Gallatin landform but near its summit is composed of volcanic deposits that appear to be from the Absarokas. Absaroka volcanism, which occurred about 53 to 43 million years ago, was widespread across the region. Could it simply be that the sources of these deposits were located far from Sepulcher Mountain and eruptive processes transported the deposits to their current location? A magmatic intrusion on the northern flank of Electric Peak that shares the same parental magma source as the volcanics at Sepulcher Mountain suggests the source for the flows may have been local. Absaroka volcanism, which occurred about 53 to 43 million years ago, might have been widespread across the region.

This volcanism buried the then living forests, creating the Gallatin Petrified Forest in the same way as the petrified trees found throughout Yellowstone National Park. Since the Gallatin volcanism ceased, a combination of alpine glaciers toward the northern end of the range (north of Yellowstone National Park) and glacial icesheets toward the southern end of the Gallatin range (in Yellowstone National Park)modified the metamorphic, sedimentary, and volcanic rock to the landforms we see today.

The Madison Range, 30 km (20 miles) west of the Gallatin Range, is generally considered to be the northwestern boundary of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE). Although the Madison Range does not share an identical history to the Gallatin Range, the Madison Range is composed of old metamorphic rocks, younger sedimentary rocks, and even younger volcanics with a similar period of deformation, making the Madison Range not terribly unlike the Gallatin Range. Likewise, the Tobacco Root and Gravelly ranges, another 30 km (20 miles) west of the Madison Range and sometimes considered as the more inclusive northwestern extent of the GYE, also share evidence of similar geologic histories as the Madison and Gallatin ranges.

Although no longer volcanically active, these ranges still present potential for geohazards. Preliminary research indicates that roughly 20% of the Gallatin and Madison ranges may be some form of mass wasting deposit from landslides, debris flows, mudflows, slumps, creep, and rockfall. Part of the mass wasting may be the result of glacial debuttressing (when glaciers melt and expose steep terrain that then collapses), but with the GYE being seismically active, seismicity may have contributed to these mass wasting events as well. With seismicity presenting a hazard (for example, the 1959 Hebgen Lake Earthquake), some faults associated with the Gallatin Range are the target of research to constrain the rate at which the ground is deforming and the likelihood of future strong earthquakes.