The ASTER instrument was the result of a partnership between NASA and Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, which built it. Technology has greatly changed since ASTER launched at the end of the last century—on December 18, 1999. At the time, just a few people had primitive smartphones, and most people who had internet connected via dial-up.

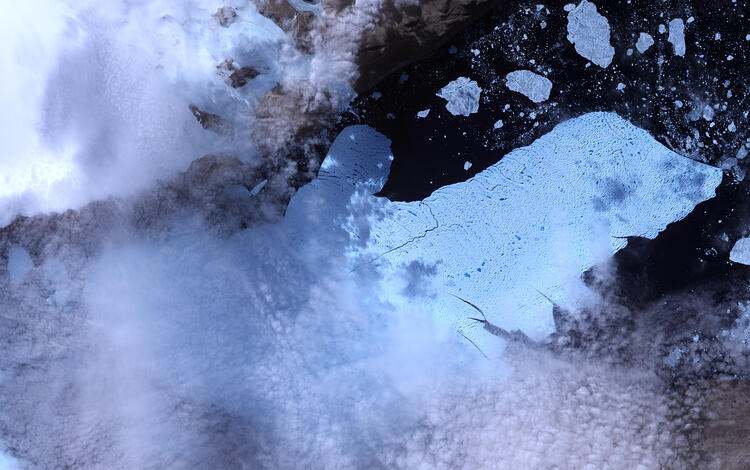

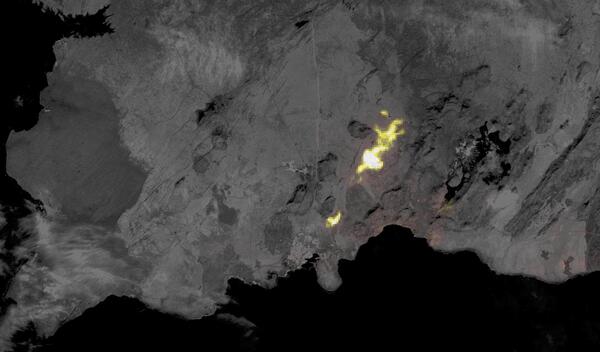

Technical constraints limited the ability to record and downlink ASTER data, as well as processing capacity and storage capacity. As a result, ASTER still can collect data for only 8 minutes of every 99-minute orbit, which adds as many as 700 daytime and nighttime images per day to the archive. Image collection is selective, prioritizing significant land features that ASTER captures well such as volcanoes and glaciers, areas recently affected by natural disasters, special requests from data users, and then filling in with the rest of the Earth’s land surfaces.

ASTER captures data in an area that’s 60 by 60 kilometers, with spatial resolutions ranging from 15 to 90 meters—much higher than other instruments on Terra, such as MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer), whose best resolution is 250 meters.

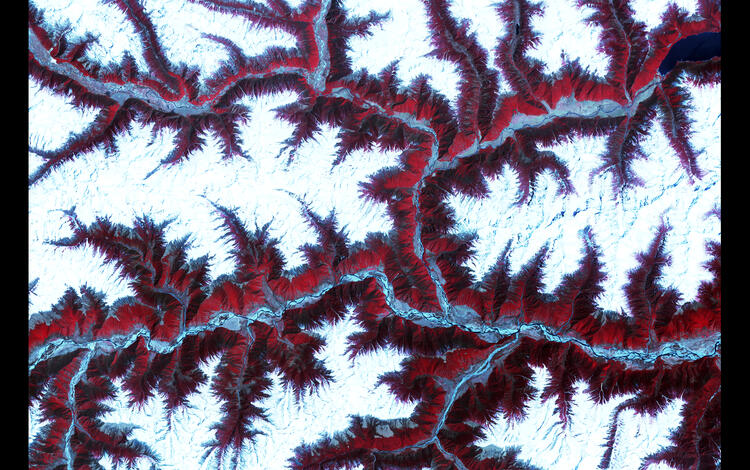

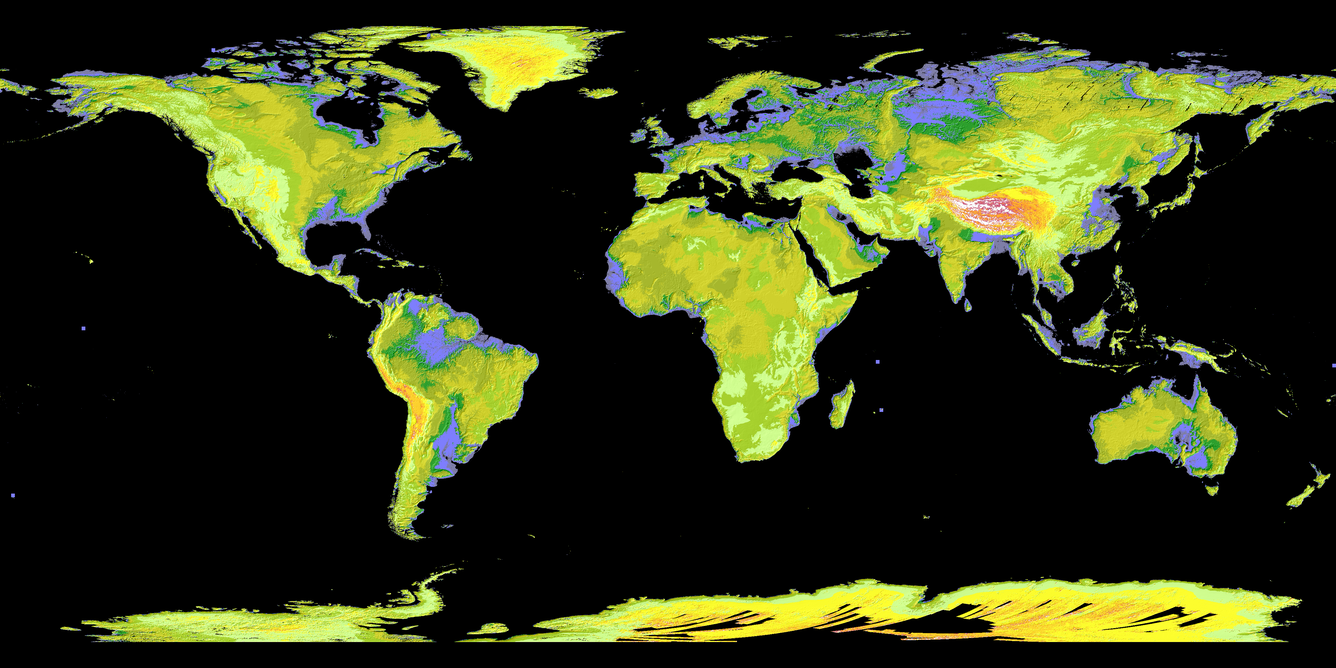

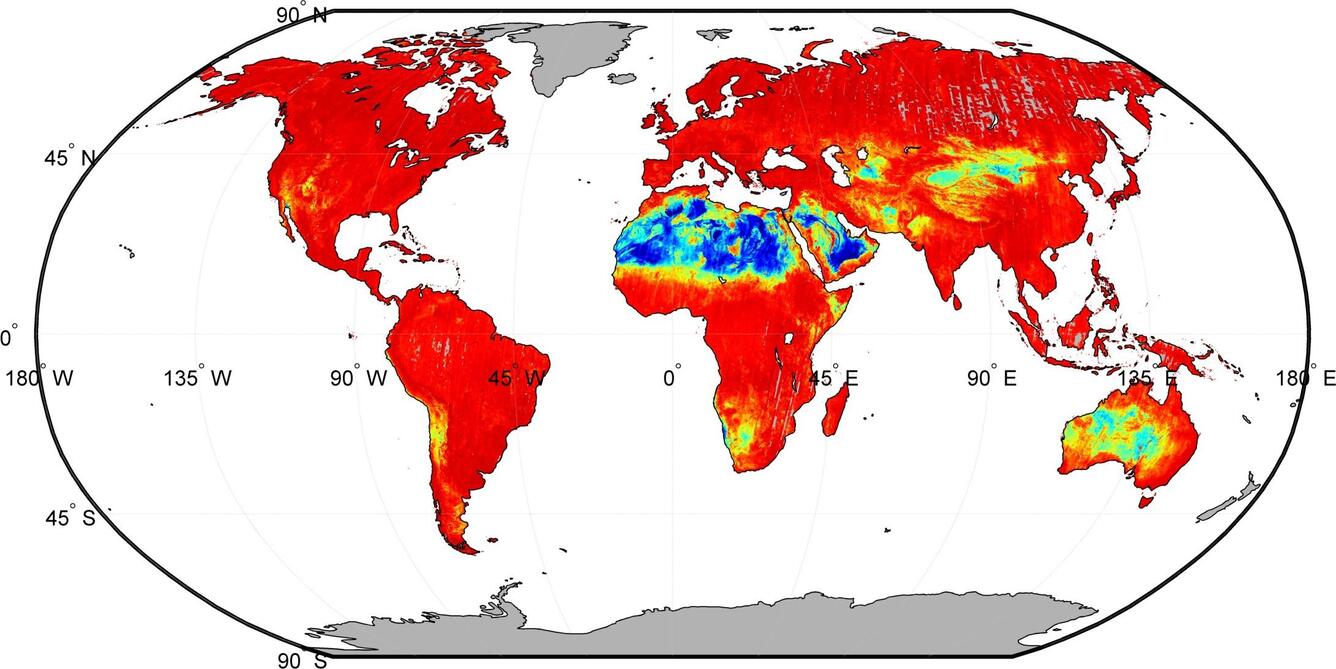

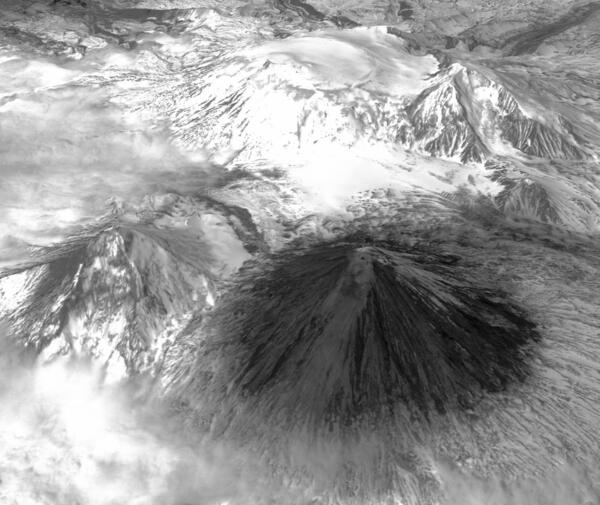

Especially notable are ASTER’s capabilities of capturing thermal infrared imagery in five wavelengths on the electromagnetic spectrum, called bands, and capturing imagery from two directions to produce a 3D-like image that is used to generate digital elevation models (DEMs). Altogether, ASTER was designed with 14 visible and infrared bands.

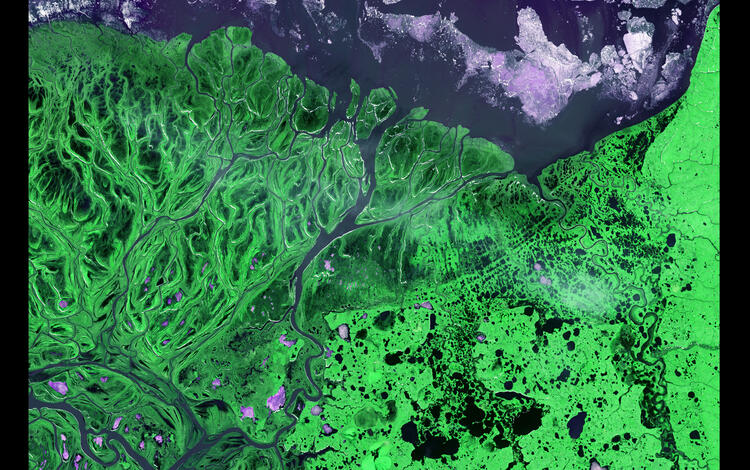

ASTER data have yielded a variety of uses, including glacier, volcano and hazard monitoring, vegetation and ecosystem dynamics, hydrology, geology and soils, and land surface and land cover change.

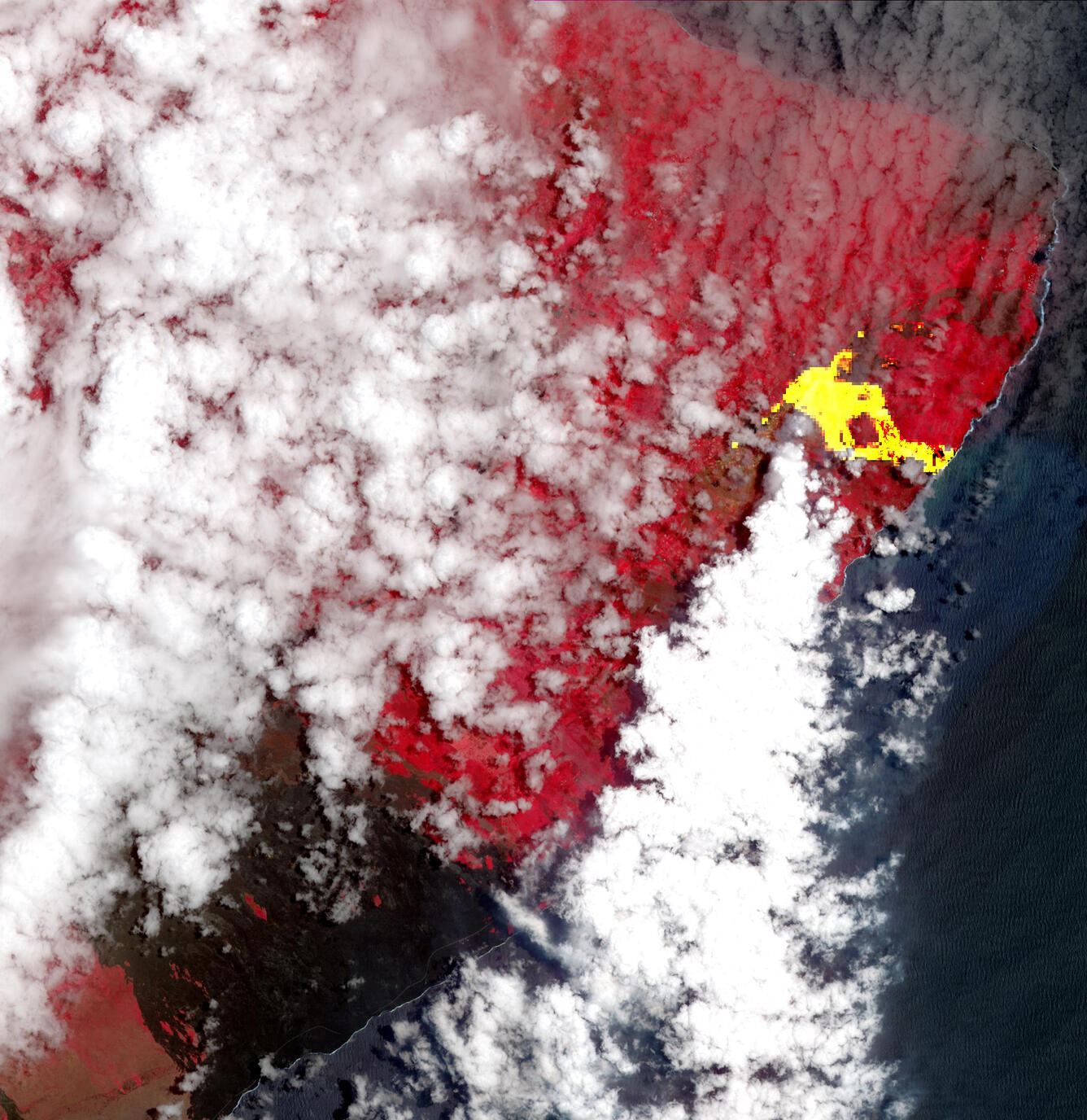

Background: This ASTER image from May 22, 2018, of an eruption at Kilauea in Hawaii displays vegetation in red, clouds in white and the hot lava flows, detected by ASTER's thermal infrared channels, overlaid in yellow. Lava flows from the eruption had reached the ocean, and the combination of molten lava and seawater produced clouds of noxious gases, such as hydrogen sulfide. Image courtesy of NASA.