Vacuolar Myelinopathy in an American Coot

American Coots (Fulica americana)

History: An American Coot (Fulica americana) was observed with neurologic signs in North Carolina, USA. The coot was euthanized and submitted to the U.S. Geological Survey National Wildlife Health Center for examination.

Gross Findings: On external examination, the keel is mildly prominent. On internal examination, there is mild to moderate atrophy of adipose tissue. There are no other significant findings.

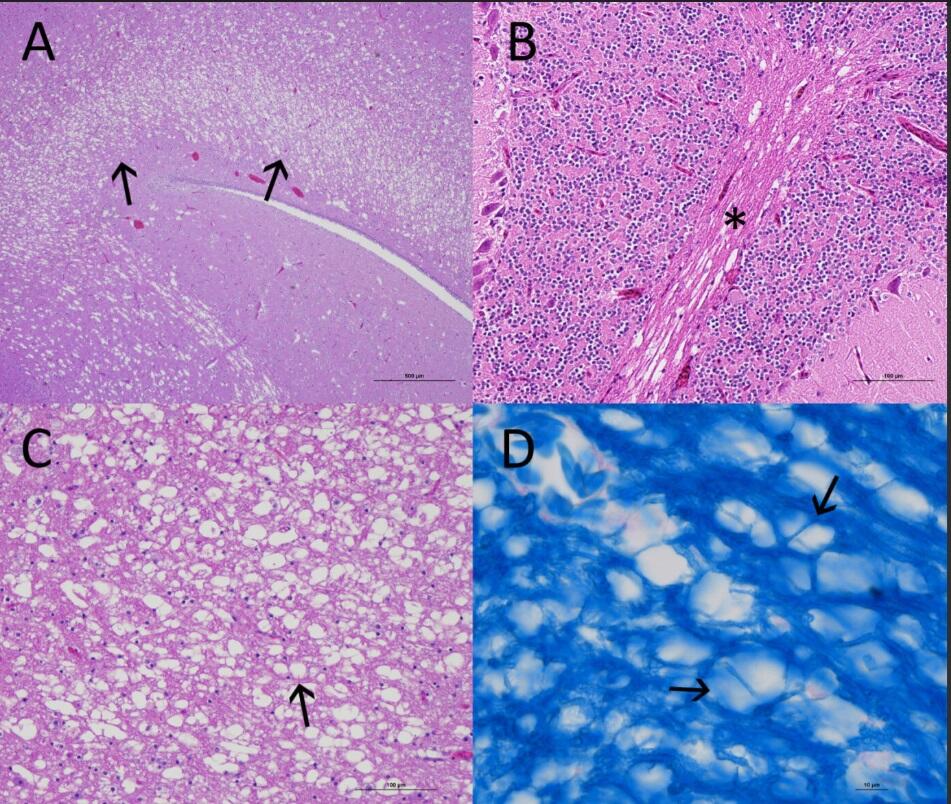

Histopathological Findings: In the brain, there is diffuse vacuolation of white matter in myelinated regions of the optic lobe (Fig 1A), the optic chiasm, the cerebellar folia (Fig 1B), and the brainstem. Most vacuoles are single, round and empty; axons are missing, or occasionally, remnants are present in the periphery of the vacuole (Fig 1C). Some vacuoles are present in pairs or small clusters divided by thin strands of myelin (Fig 1D).

Figure 1 A. Optic lobe: Severe vacuolation/spongy degeneration of the stratum opticom and stratum album centrale of an American Coot (Fulica americana). H&E stain. Figure 1B. Diffuse vacuolation of the white matter of the cerebellar folia. H&E stain. Figure 1C. Vacuoles are mostly round and empty; axons are missing. H&E stain. Figure 1D. Vacuoles present in pairs or clusters are separated by thin strands of myelin. Luxol Fast Blue Stain.

Morphologic Diagnosis: Severe diffuse vacuolar leukoencephalopathy.

Disease: (Avian) Vacuolar Myelinopathy (VM).

Etiology: Aetokthonotoxin (AETX), a lipophilic neurotoxin produced by cyanobacterium (Aetokthonos hydrillicola) which grows on submerged aquatic vegetation, such as Hydrilla (Hydrilla verticillate), Brazilian elodea (Egeria densa), and Eurasian watermilfoil (Myriophyllum spicatum).

Distribution: Presence of toxic A. hydrillicola has been confirmed in artificially made bodies of water throughout the southeastern United States: Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Texas, though true distribution of the agent is not fully known.

Seasonality: Vacuolar myelinopathy outbreaks have been linked with colder months, during late fall and early winter (November – March). There is seasonal variation in AETX accumulation in the submerged aquatic vegetation. Colder water temperatures and seasonal changes in abiotic and biotic factors in water bodies promote a bromide-rich environment, prompting AETX production.

Host range: Waterfowl and raptors, including but not limited to American coots (Fulica americana), mallards (Anas platyrhynchos), ring-necked ducks (Aythya collaris), buffleheads (Bucephala albeola), Canada geese (Branta candadensis), bald eagles (Haliaeetus leuocephalus), great-horned owls (Bubo virginianus), and killdeer (Charadrius vociferus). Vacuolar myelinopathy has also been experimentally reproduced in red-tailed hawks (Buteo jamacensis) and chickens (Gallus gallus domesticus).

Transmission: Transmission is through ingestion of toxin produced by A. hydrillicola. For waterfowl, transmission occurs when they consume aquatic vegetation with associated A. hydrillicola present, ultimately resulting in intoxication and accumulation of toxin in tissues. Birds of prey are exposed when they feed on moribund (sick) waterfowl. Other prey including snails, fish, and turtles have experimentally demonstrated intoxication with A. hydrillicola, serving as a potential alternative source of transmission.

Clinical Signs: Affected birds typically display neurologic signs such as incoordination or ataxia, difficulty in or inability to walk, swim, or fly.

Pathology: Gross lesions are not readily apparent. Microscopically, vacuolar lesions are present in the myelinated axons (white matter) of the brain, particularly the optic lobe, cerebellar folia, and medulla oblongata, and the spinal cord.

Diagnosis: A presumptive diagnosis is based on location with known or suspected history of VM, in conjunction with cyanobacteria supporting vegetation presence, and histologic confirmation of vacuolation in the white matter of central nervous system tissues.

Public Health Concerns: While there are none known at this time, the possible effects of AETX on humans have not been determined.

Wildlife Population Impacts: Aetokthonotoxin is found in select water bodies impacting various avian species. Additionally, due to the lipophilicity of this toxin and the ability to accumulate in tissues, there is evidence that diverse food webs are affected. However, the population level impacts of VM in coots and other waterfowl has not yet been described.

Management: Much of the management strategies have been targeted at the removal of invasive submerged aquatic vegetation. Diquat bromide containing herbicides have been used to kill submerged aquatic vegetation. Triploid grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) have been implemented in biological control strategies to consume excess grasses; however, there is concern about unintended consequences of biological control strategies. Furthermore, triploid grass carp are susceptible to VM lesions. Physical removal has limited success due to plants’ ability to reproduce from fragments, tubers, and turions.

References:

Breinlinger S, Phillips TJ, Haram BN, Mareš J, Martínez Yerena JA, Hrouzek P, Sobotka R, Henderson WM, Schmieder P, Williams SM, Lauderdale JD, Wilde HD, Gerrin W, Kust A, Washington JW, Wagner C, Geier B, Liebeke M, Enke H, Niedermeyer THJ, Wilde SB. 2021. Hunting the eagle killer: A cyanobacterial neurotoxin causes vacuolar myelinopathy. Science 371(6536):eaax9050. doi: 10.1126/science.aax9050. PMID: 33766860; PMCID: PMC8318203.

Dodd SR, Haynie RS, Williams SM, Wilde SB. 2016. Alternate food-chain transfer of the toxin linked to avian vacuolar myelinopathy and implications for the endangered Florida snail kite (Rostrhamus sociabilis). J Wildl Dis 52(2):335-44. doi: 10.7589/2015-03-061. PMID: 26981686.

Fischer JR, Lewis-Weis LA, Tate CM. 2003. Experimental vacuolar myelinopathy in red-tailed hawks. J Wildl Dis 39(2):400-6. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-39.2.400. PMID: 12910768.

Rocke TE, Thomas NJ, Meteyer CU, Quist CF, Fischer JR, Augspurger T, Ward SE. 2005. Attempts to identify the source of avian vacuolar myelinopathy for waterbirds. J Wildl Dis 41 (1): 163–170. doi: https://doi.org/10.7589/0090-3558-41.1.163

Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study. 2021. Field Manual of Wildlife Diseases in the Southeastern United States. Fourth edition, Athens, GA.

Thomas NJ, Meteyer CU, Sileo L. 1998. Epizootic vacuolar myelinopathy of the central nervous system of bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) and American coots (Fulica americana). Vet Pathol 35(6):479-87. doi: 10.1177/030098589803500602. PMID: 9823589.

Wilde SB, Murphy TM, Hope CP, Habrun SK, Kempton J, Birrenkott A, Wiley F, Bowerman WW, Lewitus AJ. 2005. Avian vacuolar myelinopathy linked to exotic aquatic plants and a novel cyanobacterial species. Environ Toxicol 20(3):348-53. doi: 10.1002/tox.20111. PMID: 15892059.

Wiley FE, Wilde SB, Birrenkott AH, Williams SK, Murphy TM, Hope CP, Bowerman WW, Fischer JR. 2007. Investigation of the link between avian vacuolar myelinopathy and a novel species of cyanobacteria through laboratory feeding trials. J Wildl Dis 43(3):337-44. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-43.3.337. PMID: 17699072.