Defining the Anthropocene via the Transport of Invasive Species

Planetary-scale change to the biosphere signalled by global species translocations can be used to identify the Anthropocene

Palaeontological signatures of the Anthropocene are distinct from those of previous epochs

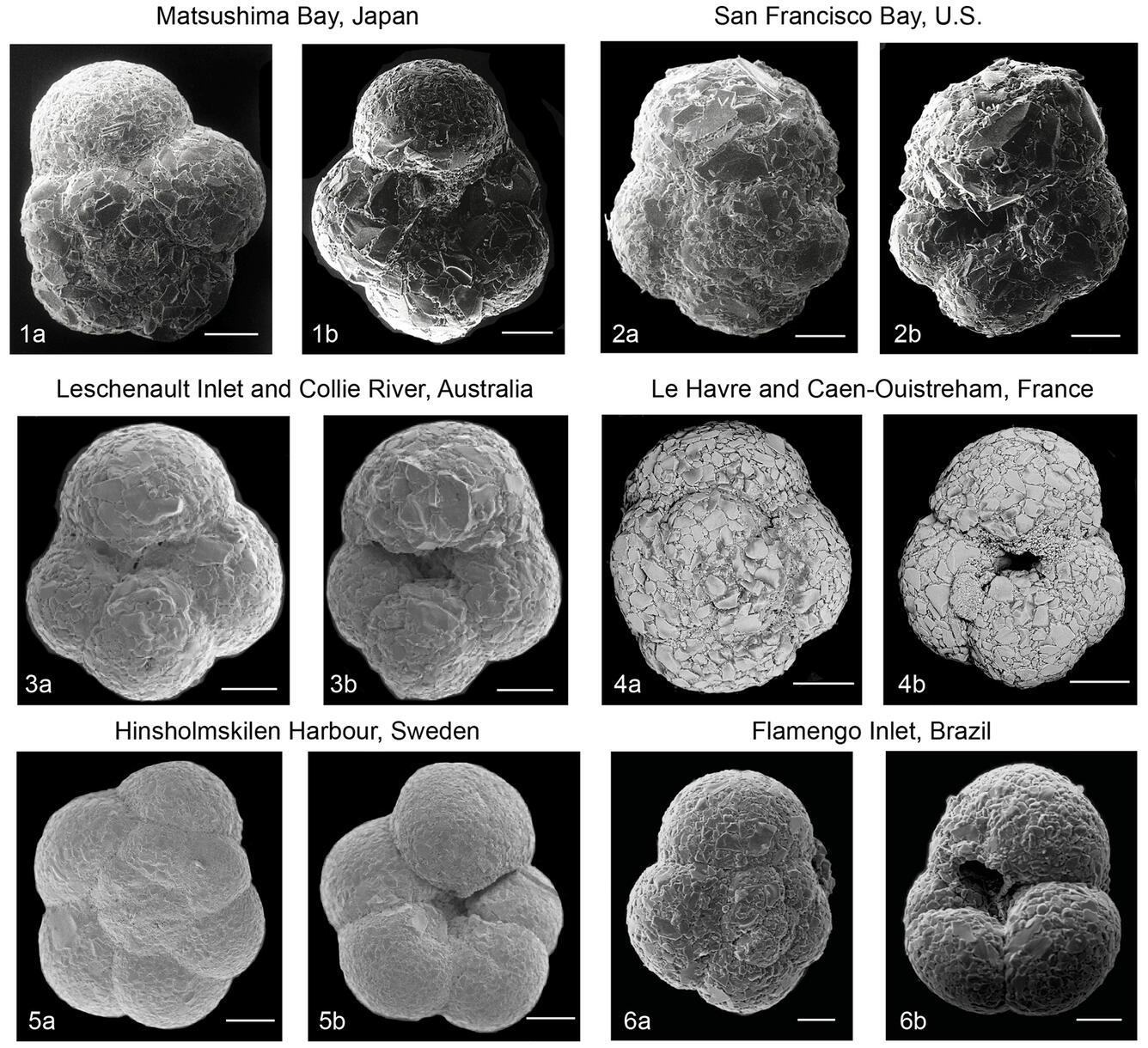

Analysis of a human-mediated microbioinvasion: the global spread of the benthic foraminifer Trochammina hadai Uchio, 1962

A team of researchers has analyzed fossil evidence around the world and found that globalization—the massive expansion of worldwide trade and commerce during the early 20th century—has left a distinct paleontological record of introduced species that corresponds to specific periods in Earth's history.

The impacts of humankind on the natural world are manifold, and in many cases, long-lasting. From the domestication of crops and livestock to the edifices of civilization, from the Industrial Revolution to the development of the nuclear bomb, the influence of humans on Earth’s systems is so profound and unmistakable that researchers have proposed a new geologic epoch to describe it: the Anthropocene.

Geologic epochs can span millions of years. What separates one epoch from another are layers of rock, or strata, that correspond to a specific time in the past. The geologic record on earth is composed of these strata, which contain time-stamped clues to changes in atmosphere, geology, chemistry, and biology that define each epoch. For instance, a stratum containing fossilized plant and animal remains provides paleontological evidence of a particular environment at a particular period; underlying this stratum might be the fossils of plants and animals that preceded them.

The current epoch is the Holocene, which began 11,700 years ago after the last major ice age. To define the start of the Anthropocene, researchers need a unique geologic datum, a distinguishable piece of evidence in the geologic record—a fossil, a chemical signature, a novel mineral or sediment layer—that appears around the same time in similar settings worldwide and separates the Holocene from the Anthropocene.

A team of researchers has analyzed fossil evidence around the world and found that globalization—the massive expansion of worldwide trade and commerce during the early 20th century—has left a distinct paleontological record of introduced species that corresponds to specific periods in Earth's history.

In a series of recent studies, the researchers find that a paleontological record of species spread through globalization—not a single species but many, including cultivated plants, bivalves, water fleas, and single-celled marine organisms called Foraminifera—can be interwoven to serve as a reliable marker for the Anthropocene, dovetailing with other markers such as geochemical evidence of the Industrial Revolution, or the nuclear signature left by the detonation of atomic bombs during World War II.

“We have impacted the environment in so many different ways, with ample evidence to show for it. But this research is the first time that a global record of species introductions has been shown to correlate with other known markers of the Anthropocene,” said Mary McGann, USGS Research Geologist at the Pacific Coastal and Marine Science Center and a co-author of the studies.

Focusing on a Far-flung Foram

For this research, McGann focused on the single-celled foraminifer Trochammina hadai. Originally native to Asia, these tiny creatures live in soft sediments on the seafloor. With the advent of global maritime shipping in the early 20th century, ships that carried goods from Asia to ports beyond inadvertently transported T. hadai in their ballast water and ballast sediment, which is released when ships arrive at port to unload their cargo. T. hadai proved very amenable to these translocations and soon outcompeted other, native foraminifers.

Like most foraminifers, T. hadai protects itself by building an exoskeleton called a test around its body. These tests litter the substrate where T. hadai occurs and are durable enough to fossilize over time. Although T. hadai is among a group of foraminifers that builds their tests out of sand grains, most others do so out of calcium carbonate. By carbon-dating the calcium carbonate tests in sediment samples, it is possible to determine when the associated non-native foraminifers arrived in the fossil record. Samples taken from other parts of the world could then be used to create a timeline of T. hadai’s spread, which generally corresponds to the pace of globalization.

“The Anthropocene is often considered the point in time at which humans began to substantially alter the environment,” said McGann. “Whether or not we describe it as a new geological epoch, the evidence that we are rapidly changing the planet is clear and growing, and this work adds to that conclusion.”