White-Nose Syndrome and Bat Health: 2025 Year in Review

USGS scientists have developed novel tools and techniques for national white-nose syndrome (WNS) detection and research efforts. Our scientists are monitoring bat populations (NABat) and bat behavior in addition to assessing the impact of WNS on bat populations. USGS is now focusing on disease management strategies to reverse bat declines from WNS.

Although cryptic, bats are important natural predators of insects, reducing pests so the public can enjoy the outdoors and contributing to the outdoor recreational economy. Little brown bats weigh about half an ounce but can eat 1000 mosquitoes per hour! In addition to eating mosquitoes that can spread diseases, bats eat crop pests (like the Corn earworm moth) and forest pests (like the emerald ash borer beetle). USGS scientists and partners found that by naturally suppressing crop pests through predation, bats save U.S. farmers billions of dollars annually because they provide a natural alternative to chemical pesticides. Bats are also captivating to the public with a USGS study finding that recreational visitors across six southwestern states for bat (Tadarida brasiliensis mexicana) viewing brought in over \$6.5M in consumer surplus.

Since the winter of 2006-07, millions of North American bats have died from white-nose syndrome (WNS). As of December 2025, bats with WNS were confirmed in 41 states and five Canadian provinces.

White-nose syndrome gets its name from the white fungus, Pseudogymnoascus destructans, which infects the skin on the muzzle, ears, and wings of hibernating bats and was discovered by USGS scientists.

USGS scientists have developed novel tools and techniques for national WNS detection and research efforts. Our scientists are monitoring bat populations (NABat) and bat behavior in addition to assessing the impact of WNS on bat populations. USGS is now focusing on disease management strategies to reverse bat declines from WNS.

Why is the USGS still investigating white-nose syndrome in 2025?

Bats are vital for ecosystems, providing services such as pollination and insect control that support agriculture and healthy environments.

White-nose syndrome, caused by the invasive fungus Pseudogymnoascus destructans (Pd), infects bats when they are most vulnerable—during hibernation—and has spread across most of North America. This disease has caused mass mortality in bats, with affected populations of at least three species declining by more than 90%.

Major knowledge gaps remain regarding how to implement solutions to improve the survival of bats with WNS and reduce the abundance of PD in the environment.

Therefore, filling research needs to inform management decisions and optimizing tools like the WNS vaccine are urgent priorities. Without more research, WNS threatens biodiversity and the ecosystem services bats provide.

Three of the most impactful white-nose syndrome and USGS bat health science accomplishments in 2025

WNS and Rabies Vaccines

How is WNS impacting western bat populations?

How can managers understand the true impact of WNS on bat populations?

What is the most effective way to deliver a vaccine to wild bats?

Scientists at the USGS National Wildlife Health Center have been working on vaccines to protect bats from diseases such as rabies and white-nose syndrome. The most promising delivery method is called orotopical vaccination. By applying the vaccine to the bat’s back, the gel-based vaccine is spread to others in the colony through grooming. This turns a small application into a colony-wide vaccination effort.

The vaccine is mixed into a carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) gel, a safe substance made from plant fibers. This gel is ideal because:

- It stays stable in temperatures from freezing to hot (0°C–40°C).

- It keeps the vaccine effective for months without needing special refrigeration.

- It works even if applied to only a small number of bats, thanks to their social behavior.

This strategy is called ring vaccination and is often focused on juvenile bats first. This approach could stop rabies from spreading more effectively than culling (killing bats) and could also be used for other diseases like white-nose syndrome.

USGS Science in the Media

- Read the Science magazine article about this research.

- Watch the PBS special on the WNS response that features USGS scientist Tonie Rocke and the WNS vaccine.

Yuma myotis

With a wingspan the size of an iPad and a two-inch body length, Yuma myotis is a common western insect-eating bat. It is found in 13 states, and its range extends from British Columbia to Mexico. Because it can’t concentrate its urine well, it needs to drink a lot and is more closely associated with water than any bat species in North America. These bats can be found with a handful of other individuals or thousands can gather in natural (caves, crevices, trees) or artificial (bridges, buildings, mines) roosting sites for hibernation (winter) or maternity colonies (summer); males are generally solitary.

How is WNS impacting Yuma myotis (a western bat species)?

In 2025, the USGS reported on WNS-associated mortality (die-off) events in Yuma myotis in Washington state. The USGS National Wildlife Health Center performed cause-of-death investigations on the Yuma myotis mortality events in Washington state in 2020, 2021, and 2024. WNS was associated with significant mortality in this species, and the impact was likely underestimated due to the inaccessibility of their hibernating spaces for monitoring.

The North American Bat Monitoring Program’s (NABat) monitoring (acoustic surveys and summer roost counts) could be used to better assess the impacts of WNS on this western species.

Tricolored Bat

The tricolored bat (Perimyotis subflavus) is one of the smallest North American bats, easily recognized by its unique three-banded fur and pinkish forearms. Found east of the Rocky Mountains in 39 states and Washington D.C., it roosts in tree foliage during summer and hibernates in caves, culverts, or bridges in winter. Females form small maternity colonies and typically give birth to twins. Highly sensitive to white-nose syndrome, this species has experienced severe population declines and USFWS has proposed listing the tricolored bat as endangered under the Endangered Species Act.

How can managers understand the true impact of WNS on bat populations?

In this data modeling publication, USGS scientists developed a novel tool to analyze multiple bat monitoring data streams to understand the impact of WNS on tri-colored bats.

Monitoring cryptic bat populations is challenging and requires multiple data sources. NABat collects acoustic, capture, and winter colony data and these provide complementary insights into occupancy (where bats are found on the landscape) and abundance (number of individual bats at a specific location).

But traditional analyses treat these data streams separately, leading to inconsistent conclusions related to the impact of WNS: occupancy trends appear relatively stable while abundance declines catastrophically. This mismatch creates confusion for conservation planning and obscures the true population impacts.

Therefore, USGS scientists developed a multi-scale integrated species distribution model that combines all monitoring types, accounts for false positives and negatives, and links seasonal populations through migratory connectivity. Applying this model to 11 years of data for the tricolored bat revealed:

- Abundance declined by ~75%, while occupancy declined by ~35%.

- Declines were spatially asynchronous: abundance dropped most in WNS-affected interiors, but occupancy fell mainly at the edges of the species’ range.

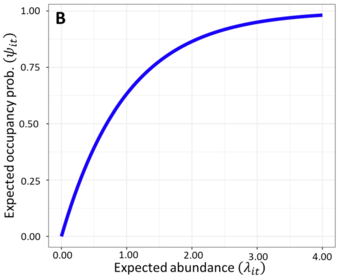

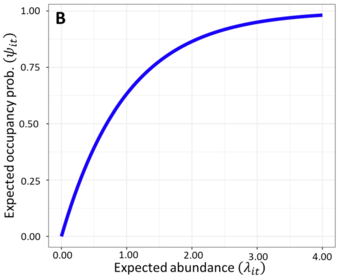

- The connection between how many bats there are and whether they occupy an area is positive but not a straight line. It levels off, meaning occupancy stays high until bat numbers get very close to zero.

- The integrated model reduced uncertainty by up to 86% compared to independent analyses and offers a powerful tool for conservation decisions under emerging disease threats.

Explore the 2025 white-nose syndrome and bat health publications >>

North American Bat Monitoring Program (NABat)

Fish & Wildlife Disease: White-Nose Syndrome

U.S. Geological Survey science strategy to address white-nose syndrome and bat health in 2025–2029 U.S. Geological Survey science strategy to address white-nose syndrome and bat health in 2025–2029

U.S. Geological Survey science strategy to address white-nose syndrome and bat health in 2025–2029 U.S. Geological Survey science strategy to address white-nose syndrome and bat health in 2025–2029

White-nose syndrome surveillance and bat monitoring activities in North Coast and Cascades Network parks 2016–2024 White-nose syndrome surveillance and bat monitoring activities in North Coast and Cascades Network parks 2016–2024

Estimating disease prevalence from preferentially sampled, pooled data Estimating disease prevalence from preferentially sampled, pooled data

Integrated distribution modeling resolves asynchrony between bat population impacts and occupancy trends through latent abundance Integrated distribution modeling resolves asynchrony between bat population impacts and occupancy trends through latent abundance

Learning complex spatial dynamics of wildlife diseases with machine learning-guided partial differential equations Learning complex spatial dynamics of wildlife diseases with machine learning-guided partial differential equations

A novel method for estimating pathogen presence, prevalence, load, and dynamics at multiple scales A novel method for estimating pathogen presence, prevalence, load, and dynamics at multiple scales

Mortality events in Yuma myotis (Myotis yumanensis) due to white-nose syndrome in Washington, USA Mortality events in Yuma myotis (Myotis yumanensis) due to white-nose syndrome in Washington, USA

The importance of peripheral populations in the face of novel environmental change The importance of peripheral populations in the face of novel environmental change

Disparities in Perimyotis subflavus body mass between cave and culvert hibernacula in Georgia, USA Disparities in Perimyotis subflavus body mass between cave and culvert hibernacula in Georgia, USA

Quantification of threats to bats at localized spatial scales for conservation and management Quantification of threats to bats at localized spatial scales for conservation and management

USGS scientists have developed novel tools and techniques for national white-nose syndrome (WNS) detection and research efforts. Our scientists are monitoring bat populations (NABat) and bat behavior in addition to assessing the impact of WNS on bat populations. USGS is now focusing on disease management strategies to reverse bat declines from WNS.

Although cryptic, bats are important natural predators of insects, reducing pests so the public can enjoy the outdoors and contributing to the outdoor recreational economy. Little brown bats weigh about half an ounce but can eat 1000 mosquitoes per hour! In addition to eating mosquitoes that can spread diseases, bats eat crop pests (like the Corn earworm moth) and forest pests (like the emerald ash borer beetle). USGS scientists and partners found that by naturally suppressing crop pests through predation, bats save U.S. farmers billions of dollars annually because they provide a natural alternative to chemical pesticides. Bats are also captivating to the public with a USGS study finding that recreational visitors across six southwestern states for bat (Tadarida brasiliensis mexicana) viewing brought in over \$6.5M in consumer surplus.

Since the winter of 2006-07, millions of North American bats have died from white-nose syndrome (WNS). As of December 2025, bats with WNS were confirmed in 41 states and five Canadian provinces.

White-nose syndrome gets its name from the white fungus, Pseudogymnoascus destructans, which infects the skin on the muzzle, ears, and wings of hibernating bats and was discovered by USGS scientists.

USGS scientists have developed novel tools and techniques for national WNS detection and research efforts. Our scientists are monitoring bat populations (NABat) and bat behavior in addition to assessing the impact of WNS on bat populations. USGS is now focusing on disease management strategies to reverse bat declines from WNS.

Why is the USGS still investigating white-nose syndrome in 2025?

Bats are vital for ecosystems, providing services such as pollination and insect control that support agriculture and healthy environments.

White-nose syndrome, caused by the invasive fungus Pseudogymnoascus destructans (Pd), infects bats when they are most vulnerable—during hibernation—and has spread across most of North America. This disease has caused mass mortality in bats, with affected populations of at least three species declining by more than 90%.

Major knowledge gaps remain regarding how to implement solutions to improve the survival of bats with WNS and reduce the abundance of PD in the environment.

Therefore, filling research needs to inform management decisions and optimizing tools like the WNS vaccine are urgent priorities. Without more research, WNS threatens biodiversity and the ecosystem services bats provide.

Three of the most impactful white-nose syndrome and USGS bat health science accomplishments in 2025

WNS and Rabies Vaccines

How is WNS impacting western bat populations?

How can managers understand the true impact of WNS on bat populations?

What is the most effective way to deliver a vaccine to wild bats?

Scientists at the USGS National Wildlife Health Center have been working on vaccines to protect bats from diseases such as rabies and white-nose syndrome. The most promising delivery method is called orotopical vaccination. By applying the vaccine to the bat’s back, the gel-based vaccine is spread to others in the colony through grooming. This turns a small application into a colony-wide vaccination effort.

The vaccine is mixed into a carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) gel, a safe substance made from plant fibers. This gel is ideal because:

- It stays stable in temperatures from freezing to hot (0°C–40°C).

- It keeps the vaccine effective for months without needing special refrigeration.

- It works even if applied to only a small number of bats, thanks to their social behavior.

This strategy is called ring vaccination and is often focused on juvenile bats first. This approach could stop rabies from spreading more effectively than culling (killing bats) and could also be used for other diseases like white-nose syndrome.

USGS Science in the Media

- Read the Science magazine article about this research.

- Watch the PBS special on the WNS response that features USGS scientist Tonie Rocke and the WNS vaccine.

Yuma myotis

With a wingspan the size of an iPad and a two-inch body length, Yuma myotis is a common western insect-eating bat. It is found in 13 states, and its range extends from British Columbia to Mexico. Because it can’t concentrate its urine well, it needs to drink a lot and is more closely associated with water than any bat species in North America. These bats can be found with a handful of other individuals or thousands can gather in natural (caves, crevices, trees) or artificial (bridges, buildings, mines) roosting sites for hibernation (winter) or maternity colonies (summer); males are generally solitary.

How is WNS impacting Yuma myotis (a western bat species)?

In 2025, the USGS reported on WNS-associated mortality (die-off) events in Yuma myotis in Washington state. The USGS National Wildlife Health Center performed cause-of-death investigations on the Yuma myotis mortality events in Washington state in 2020, 2021, and 2024. WNS was associated with significant mortality in this species, and the impact was likely underestimated due to the inaccessibility of their hibernating spaces for monitoring.

The North American Bat Monitoring Program’s (NABat) monitoring (acoustic surveys and summer roost counts) could be used to better assess the impacts of WNS on this western species.

Tricolored Bat

The tricolored bat (Perimyotis subflavus) is one of the smallest North American bats, easily recognized by its unique three-banded fur and pinkish forearms. Found east of the Rocky Mountains in 39 states and Washington D.C., it roosts in tree foliage during summer and hibernates in caves, culverts, or bridges in winter. Females form small maternity colonies and typically give birth to twins. Highly sensitive to white-nose syndrome, this species has experienced severe population declines and USFWS has proposed listing the tricolored bat as endangered under the Endangered Species Act.

How can managers understand the true impact of WNS on bat populations?

In this data modeling publication, USGS scientists developed a novel tool to analyze multiple bat monitoring data streams to understand the impact of WNS on tri-colored bats.

Monitoring cryptic bat populations is challenging and requires multiple data sources. NABat collects acoustic, capture, and winter colony data and these provide complementary insights into occupancy (where bats are found on the landscape) and abundance (number of individual bats at a specific location).

But traditional analyses treat these data streams separately, leading to inconsistent conclusions related to the impact of WNS: occupancy trends appear relatively stable while abundance declines catastrophically. This mismatch creates confusion for conservation planning and obscures the true population impacts.

Therefore, USGS scientists developed a multi-scale integrated species distribution model that combines all monitoring types, accounts for false positives and negatives, and links seasonal populations through migratory connectivity. Applying this model to 11 years of data for the tricolored bat revealed:

- Abundance declined by ~75%, while occupancy declined by ~35%.

- Declines were spatially asynchronous: abundance dropped most in WNS-affected interiors, but occupancy fell mainly at the edges of the species’ range.

- The connection between how many bats there are and whether they occupy an area is positive but not a straight line. It levels off, meaning occupancy stays high until bat numbers get very close to zero.

- The integrated model reduced uncertainty by up to 86% compared to independent analyses and offers a powerful tool for conservation decisions under emerging disease threats.

Explore the 2025 white-nose syndrome and bat health publications >>