Earthquake Disaster Assistance Team (EDAT)

Responding to earthquakes in other countries advances U.S. strategic interests abroad and improves the United States’ ability to reduce domestic earthquake risks and to respond to earthquake threats at home, protecting American lives, businesses, and infrastructure from disasters.

About EDAT

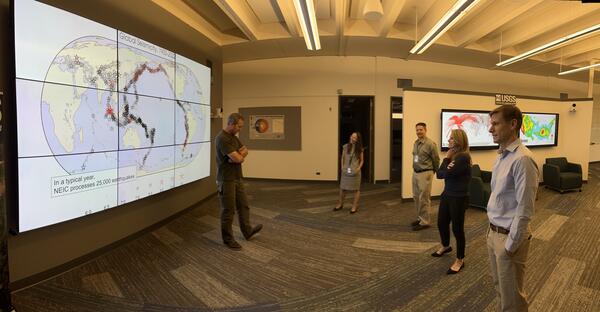

Through the Earthquake Disaster Assistance Team (EDAT), the United States Geological Survey (USGS) provides critical situational awareness, assessments, and products to the U.S. government to inform rapid humanitarian response decisions. EDAT works around the world with in-country and technical counterparts before, during, and after disasters to provide global life-saving earthquake expertise, monitoring/warning systems, equipment maintenance, and hazard assessment.

EDAT works in parallel with the Landslide Disaster Assistance Team (LDAT) and the Volcano Disaster Assistance Program (VDAP).

Disaster Response

Through EDAT, USGS provides scientific and engineering expertise and information to support life-saving response efforts by the U.S. Government and other countries. EDAT response efforts can include monitoring network support, hazard assessment, damage and impact assessment, operational aftershock forecasting, civil/structural engineering expertise/advice, and risk communication. Earthquake response work by EDAT supports short- and long-term decision making related to hazard identification, earthquake monitoring, building code development, land use, and increasing earthquake readiness to reduce future losses from earthquakes and related hazards such as landslides and tsunamis.

EDAT Response to the Turkey 2023 magnitude 7.8 and 7.6 earthquakes

In response to the 2023 Türkiye earthquake sequence, the USGS conducted several post-earthquake activities aimed at reducing future earthquake losses and the need for humanitarian assistance in Turkey as well as in other seismically active regions of the world, including the United States. The U.S. has similar faults to Turkey, and the earthquake response activities conducted in 2023 are being used by USGS to reduce domestic earthquake risk.

Where We Work

EDAT responds to disasters and works internationally in areas that have high earthquake risk, where there is alignment between requests from foreign counterparts and the response readiness needs of the U.S. Government.

Earthquake Readiness for Disaster Response at Home and Abroad

Working with technical experts around the world through EDAT saves American lives and reduces the need for foreign aid. Through disaster response and related activities, the U.S. accesses critical data and builds skills that scientists and engineers use to understand and monitor earthquakes domestically and globally, improve building codes, and hone vital communication products before, during, and after major earthquakes. Providing technical expertise to help other countries to be ready to respond to earthquakes reduces the need for costly humanitarian assistance and positions the U.S. to effectively and efficiently respond to disasters at home and around the world.

Over the past two centuries, 37 U.S. States have experienced a magnitude 5 or larger earthquake, and half of all States have a significant potential for future damaging shaking. The estimated annualized losses from earthquakes for the U.S. was close to \$15 billion in 2023. These enormous costs speak to the need for U.S. interest and investment in earthquake hazard characterization and risk reduction. EDAT contributions play a key role in the nation’s risk reduction strategy.

EDAT in Action

EDAT and local organizations monitor earthquakes in the South Pacific to save lives

EDAT is currently supporting the installation of additional high-quality seismometers in the Pacific region to improve rapid earthquake and tsunami detection and characterization, enhancing U.S. government domestic and international response capabilities. The Pacific region is one of the most seismically active regions in the world and produces tsunamis that threaten the US and global coastlines in addition to producing damaging shaking in the areas impacted by earthquakes.

EDAT and partners provide aftershock forecasts for rapid earthquake response decision making

The USGS forecasts the likely size and number of earthquake aftershocks to support response activities domestically and internationally. EDAT works to improve USGS’ earthquake response products like aftershock forecasts, including understanding the needs of different stakeholder groups in the US and abroad.