Along with Tutuila and Ofu-Olosega volcanoes to the west, Ta‘ū Island is the top of a potentially active volcano within the United States Territory of American Samoa.

Ta‘ū

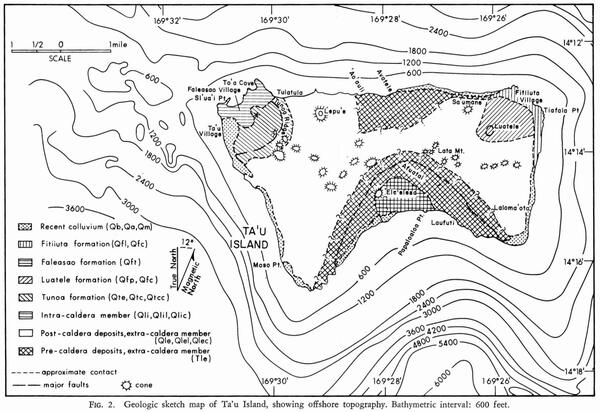

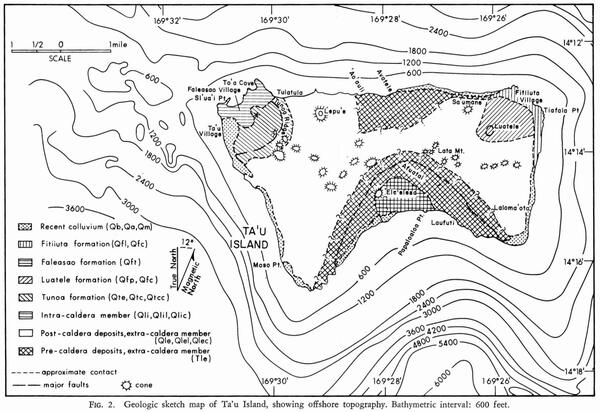

Taʻū Island is the top of a shield volcano, most of which is beneath the ocean. The top of the island is more than 3,000 feet (900 meters) above sea level, but the volcano’s flanks extend another 9,000 feet (2,700 meters) below sea level to the ocean floor. The volcano has a summit caldera, though the southern part of the caldera has largely been removed by landslides. Two rift zones are present on Taʻū, one to the northeast and one to the northwest.

The northwest rift zone of Ta‘ū aligns with the Samoan Ridge, a predominantly submarine feature formed from volcanic activity associated with the Samoa hotspot, which is currently located at the Vailulu‘u seamount 25 miles (40 kilometers) to the east of Ta‘ū Island. Ta‘ū, as well as Ofu-Olosega islands are located on the crest of the Samoan Ridge, which tracks activity of the Samoa hotspot. A vent that erupted between Ta‘ū and Ofu-Olosega in 1866 is also located on the Samoan Ridge.

The geologic history of Ta‘ū Island can be separated into several phases: a main shield volcano, called Lata, that has caldera collapse features at its summit. Post-caldera tuff cones, scoria cones, and lava flows continued to erupt, partially filling the caldera and forming two satellite shields on the flanks of the volcano: Tunoa shield on the northwest part of the island and Luatele shield on the northeast part of the island. The summits of these satellite shields also collapsed and filled with other volcanic deposits. A period of decreased volcanic activity allowed for erosion to form coastal cliffs that were later draped with lava flows, including the Fitiuta deposits erupted on the northeast rift zone. The Faleasao tuff cone was erupted on the northwest rift zone during this later period of activity and covered sea cliffs, as did later Lata lava flows and cones.

Vailulu‘u and other submarine vents

In 1866, a submarine vent erupted between Olosega and Ta‘ū Islands and formed a volcanic cone 150 feet (45 meters) below the ocean surface. The Smithsonian Institution Global Volcanism Program attributes this eruption to the Ofu-Olosega volcano but it is described below. More recently, Vailulu‘u seamount, thought to be directly above the Samoan hotspot, has erupted multiple times.

Vailulu‘u seamount is a submarine volcano located about 25 miles (45 kilometers) east of Ta‘ū Island. The seamount rises 4,200 meters (13,779 feet) from the sea floor to 593 meters (1,946 feet) below sea level. Like Hawaiian volcanoes, Vailulu‘u has a summit caldera and rift zones that host the majority of eruptions. Vailulu‘u’s caldera is 1.2 mi (2 kilometers) wide and 0.25 mi (400 meters) deep, and rift zones extend east, west, and southeast of the summit.

Vailulu‘u likely erupted in 1973, 1995, and 2003. Hydrophones recorded underwater acoustic signals that were thought to be associated with explosions in 1973, and an earthquake swarm in 1995 has been attributed to an eruption. An additional earthquake swarm occurred in 2000.

Bathymetric surveys of Vailulu‘u during a 2005 diving expedition with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Agency (NOAA) research submersible Pisces V, launched from the University of Hawaii research vessel Kaimikai O Kanaloa (KOK), showed that the 2003 eruption constructed a 980-feet (300-meter)-high cone within the summit caldera. This cone, primarily composed of pillow lavas, was named Nafanua after the Samoan Goddess of War. Another NOAA survey in 2017 documented additional growth of Nafanua cone, likely due to continuing volcanic activity. An active hydropthermal system has also been documented at Vailulu‘u.

1866 eruption between Ta‘ū and Ofu-Olosega islands

The 1866 eruption, which occurred between Ta‘ū and Ofu-Olosega islands, is the youngest documented eruption in American Samoa outside of activity at Vailulu‘u seamount 25 miles (40 kilometers) to the east of Ta‘ū Island.

In a November 26, 1866, letter printed in the Manchester Guardian newspaper on April 17, 1867 (p. 4), Reverend Dr. Turner, a missionary, provided a description of this eruption from a colleague, which is quoted below. The account summarizes a shallow submarine eruption, at least one week in duration, that likely formed a submarine tuff cone approximately 2 miles (3 km) southeast of Olosega. Volcanic tuffs are formed when eruptions occur through water, and they often occur near the coast or near offshore environment. The interaction of the lava and water results in an explosive type of eruption called a phreatomagmatic eruption. Lēʻahi (also known as Diamond Head) on the island of O‘ahu in the State of Hawaii an example of a tuff cone.

The account of the 1866 eruption below suggests that it was phreatomagmatic in nature. It describes earthquakes being felt by residents of the Manu‘a islands very often (3–4 per hour) for several days leading to the eruption. The first day of the eruption was marked by waves looking like they were breaking over shallow reef or rocks. The following five days were marked by intermittent phreatomagmatic eruptions generating “great jets of mud and dense columns of other volcanic matter” an estimated 2,000 feet (600 meters) into the air. The eruption continued, with explosive events occurring less frequently and at a lower level (an estimated 20–30 feet or 6–9 meters above sea level). The cone formed during the 1866 eruption reached to an estimated 150 feet (45 meters) below the ocean surface.

Though the 1866 eruption occurred approximately 2 miles (3 km) southeast of Olosega and stopped before the cone emerged above the ocean surface, it did impact residents of the area. Volcanic gases released during the eruption caused air pollution (vog) and tephra (small volcanic particles) was deposited downwind. Pollution of the ocean also occurred and killed fish and other nearby marine life. Earthquakes were felt by Manu‘a islands residents throughout the eruption.

Manchester Guardian newspaper on April 17, 1867 (p. 4), letter written on November 26, 1866, by Reverend Dr. Turner:

“On the 7th of September last the natives of Tau and Olosenga were surprised by an unusual succession of earthquakes—there would be three and four in the course of an hour. During the night of the 9th there were in all 30 shocks. There was only a slight tremulous motion, but its continuance, together with an unusual subterranean ‘groaning’ as the natives called it, alarmed everybody. They knew nothing of volcanic action in the group from personal experience or the traditions of their ancestors. Their islands, however, are all volcanic. On the 12th of September, a little after noon, a commotion was observed in the deep blue sea, about a mile and a half from Olosenga, and three and a half from Tau. It appeared like surf breaking over a sunken rock. Some thought it might be a whale blowing, and others that it was a shoal of bonito. The unusual commotion continued all day, and by the following morning at daylight volcanic action was unmistakable. At first the eruptions were at intervals of about an hour. They went on increasing for two days, and on the 15th they were 50 in the hour. For three days longer there was one continued succession of outbursts. The natives gazed in amazement at the great jets of mud and dense columns of other volcanic matter rising in terrific grandeur 2,000 feet above the level of the sea. These again branched out into clouds of dust blackening the sky, and covering up Olosenga from the sigh of the people on Tau. The roar of the eruptions, and the collision and crash of the masses of rock met in their downward course from the clouds by others flying up, were fearful. Quantities of fused obsidian, too, threw off the most lovely fragments, which shone and sparkled in the sunshine like thousands of pendants from a crystal gasalier. No flame appeared, and only once or twice was there a gleam of fire seen in the matter thrown up. The sea was most violently agitated, and boiled and bubbled furiously in a great basin half a mile in diameter. After a time, the ocean had a light sulphur tinge for ten miles round. Heaps of dead fish were washed ashore, and among them deep-sea monsters, six and twelve feet long, which the natives have never seen before, and for which they have no name. The sulphurous vapours, heat, and smoke, and ashes soon made the settlement on Olosenga in a line with the volcano unbearable, and the people fled to a place a little to the south. A slight tremulous motion continued to be felt on land, but no fissures opened, nor have any hot springs made their appearance. The ordinary springs of fresh water are also unaffected. After three days the violent action began to abate, and on the 11th November, when the teacher from whom I have my information left. There were only three or four in the twelve hours, and the height to which the matter was thrown was reduced to 20 or 30 feet above the level of the sea. No cone or other uplifting has appeared above the surface of the ocean, nor is there any apparent uplifting or subsidence of the adjacent small islands. The motion on Olosenga still continues, and from a tremulous agitation has become more of a sudden jerk. A suspicious shaking has commence on the east side of Tau, but on the west side, only six miles distant, all is still.”

For more information, see the Smithsonian Institution Global Volcanism Program webpages for volcanoes in American Samoa:

Volcanic hazards in the Pacific U.S. Territories Volcanic hazards in the Pacific U.S. Territories

2018 update to the U.S. Geological Survey national volcanic threat assessment 2018 update to the U.S. Geological Survey national volcanic threat assessment

Along with Tutuila and Ofu-Olosega volcanoes to the west, Ta‘ū Island is the top of a potentially active volcano within the United States Territory of American Samoa.

Ta‘ū

Taʻū Island is the top of a shield volcano, most of which is beneath the ocean. The top of the island is more than 3,000 feet (900 meters) above sea level, but the volcano’s flanks extend another 9,000 feet (2,700 meters) below sea level to the ocean floor. The volcano has a summit caldera, though the southern part of the caldera has largely been removed by landslides. Two rift zones are present on Taʻū, one to the northeast and one to the northwest.

The northwest rift zone of Ta‘ū aligns with the Samoan Ridge, a predominantly submarine feature formed from volcanic activity associated with the Samoa hotspot, which is currently located at the Vailulu‘u seamount 25 miles (40 kilometers) to the east of Ta‘ū Island. Ta‘ū, as well as Ofu-Olosega islands are located on the crest of the Samoan Ridge, which tracks activity of the Samoa hotspot. A vent that erupted between Ta‘ū and Ofu-Olosega in 1866 is also located on the Samoan Ridge.

The geologic history of Ta‘ū Island can be separated into several phases: a main shield volcano, called Lata, that has caldera collapse features at its summit. Post-caldera tuff cones, scoria cones, and lava flows continued to erupt, partially filling the caldera and forming two satellite shields on the flanks of the volcano: Tunoa shield on the northwest part of the island and Luatele shield on the northeast part of the island. The summits of these satellite shields also collapsed and filled with other volcanic deposits. A period of decreased volcanic activity allowed for erosion to form coastal cliffs that were later draped with lava flows, including the Fitiuta deposits erupted on the northeast rift zone. The Faleasao tuff cone was erupted on the northwest rift zone during this later period of activity and covered sea cliffs, as did later Lata lava flows and cones.

Vailulu‘u and other submarine vents

In 1866, a submarine vent erupted between Olosega and Ta‘ū Islands and formed a volcanic cone 150 feet (45 meters) below the ocean surface. The Smithsonian Institution Global Volcanism Program attributes this eruption to the Ofu-Olosega volcano but it is described below. More recently, Vailulu‘u seamount, thought to be directly above the Samoan hotspot, has erupted multiple times.

Vailulu‘u seamount is a submarine volcano located about 25 miles (45 kilometers) east of Ta‘ū Island. The seamount rises 4,200 meters (13,779 feet) from the sea floor to 593 meters (1,946 feet) below sea level. Like Hawaiian volcanoes, Vailulu‘u has a summit caldera and rift zones that host the majority of eruptions. Vailulu‘u’s caldera is 1.2 mi (2 kilometers) wide and 0.25 mi (400 meters) deep, and rift zones extend east, west, and southeast of the summit.

Vailulu‘u likely erupted in 1973, 1995, and 2003. Hydrophones recorded underwater acoustic signals that were thought to be associated with explosions in 1973, and an earthquake swarm in 1995 has been attributed to an eruption. An additional earthquake swarm occurred in 2000.

Bathymetric surveys of Vailulu‘u during a 2005 diving expedition with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Agency (NOAA) research submersible Pisces V, launched from the University of Hawaii research vessel Kaimikai O Kanaloa (KOK), showed that the 2003 eruption constructed a 980-feet (300-meter)-high cone within the summit caldera. This cone, primarily composed of pillow lavas, was named Nafanua after the Samoan Goddess of War. Another NOAA survey in 2017 documented additional growth of Nafanua cone, likely due to continuing volcanic activity. An active hydropthermal system has also been documented at Vailulu‘u.

1866 eruption between Ta‘ū and Ofu-Olosega islands

The 1866 eruption, which occurred between Ta‘ū and Ofu-Olosega islands, is the youngest documented eruption in American Samoa outside of activity at Vailulu‘u seamount 25 miles (40 kilometers) to the east of Ta‘ū Island.

In a November 26, 1866, letter printed in the Manchester Guardian newspaper on April 17, 1867 (p. 4), Reverend Dr. Turner, a missionary, provided a description of this eruption from a colleague, which is quoted below. The account summarizes a shallow submarine eruption, at least one week in duration, that likely formed a submarine tuff cone approximately 2 miles (3 km) southeast of Olosega. Volcanic tuffs are formed when eruptions occur through water, and they often occur near the coast or near offshore environment. The interaction of the lava and water results in an explosive type of eruption called a phreatomagmatic eruption. Lēʻahi (also known as Diamond Head) on the island of O‘ahu in the State of Hawaii an example of a tuff cone.

The account of the 1866 eruption below suggests that it was phreatomagmatic in nature. It describes earthquakes being felt by residents of the Manu‘a islands very often (3–4 per hour) for several days leading to the eruption. The first day of the eruption was marked by waves looking like they were breaking over shallow reef or rocks. The following five days were marked by intermittent phreatomagmatic eruptions generating “great jets of mud and dense columns of other volcanic matter” an estimated 2,000 feet (600 meters) into the air. The eruption continued, with explosive events occurring less frequently and at a lower level (an estimated 20–30 feet or 6–9 meters above sea level). The cone formed during the 1866 eruption reached to an estimated 150 feet (45 meters) below the ocean surface.

Though the 1866 eruption occurred approximately 2 miles (3 km) southeast of Olosega and stopped before the cone emerged above the ocean surface, it did impact residents of the area. Volcanic gases released during the eruption caused air pollution (vog) and tephra (small volcanic particles) was deposited downwind. Pollution of the ocean also occurred and killed fish and other nearby marine life. Earthquakes were felt by Manu‘a islands residents throughout the eruption.

Manchester Guardian newspaper on April 17, 1867 (p. 4), letter written on November 26, 1866, by Reverend Dr. Turner:

“On the 7th of September last the natives of Tau and Olosenga were surprised by an unusual succession of earthquakes—there would be three and four in the course of an hour. During the night of the 9th there were in all 30 shocks. There was only a slight tremulous motion, but its continuance, together with an unusual subterranean ‘groaning’ as the natives called it, alarmed everybody. They knew nothing of volcanic action in the group from personal experience or the traditions of their ancestors. Their islands, however, are all volcanic. On the 12th of September, a little after noon, a commotion was observed in the deep blue sea, about a mile and a half from Olosenga, and three and a half from Tau. It appeared like surf breaking over a sunken rock. Some thought it might be a whale blowing, and others that it was a shoal of bonito. The unusual commotion continued all day, and by the following morning at daylight volcanic action was unmistakable. At first the eruptions were at intervals of about an hour. They went on increasing for two days, and on the 15th they were 50 in the hour. For three days longer there was one continued succession of outbursts. The natives gazed in amazement at the great jets of mud and dense columns of other volcanic matter rising in terrific grandeur 2,000 feet above the level of the sea. These again branched out into clouds of dust blackening the sky, and covering up Olosenga from the sigh of the people on Tau. The roar of the eruptions, and the collision and crash of the masses of rock met in their downward course from the clouds by others flying up, were fearful. Quantities of fused obsidian, too, threw off the most lovely fragments, which shone and sparkled in the sunshine like thousands of pendants from a crystal gasalier. No flame appeared, and only once or twice was there a gleam of fire seen in the matter thrown up. The sea was most violently agitated, and boiled and bubbled furiously in a great basin half a mile in diameter. After a time, the ocean had a light sulphur tinge for ten miles round. Heaps of dead fish were washed ashore, and among them deep-sea monsters, six and twelve feet long, which the natives have never seen before, and for which they have no name. The sulphurous vapours, heat, and smoke, and ashes soon made the settlement on Olosenga in a line with the volcano unbearable, and the people fled to a place a little to the south. A slight tremulous motion continued to be felt on land, but no fissures opened, nor have any hot springs made their appearance. The ordinary springs of fresh water are also unaffected. After three days the violent action began to abate, and on the 11th November, when the teacher from whom I have my information left. There were only three or four in the twelve hours, and the height to which the matter was thrown was reduced to 20 or 30 feet above the level of the sea. No cone or other uplifting has appeared above the surface of the ocean, nor is there any apparent uplifting or subsidence of the adjacent small islands. The motion on Olosenga still continues, and from a tremulous agitation has become more of a sudden jerk. A suspicious shaking has commence on the east side of Tau, but on the west side, only six miles distant, all is still.”

For more information, see the Smithsonian Institution Global Volcanism Program webpages for volcanoes in American Samoa: