Impact of warming and suspended land-based sediment on Hawaiian reef corals

A new study from Texas A&M University, Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology, and USGS offers fresh insight into how Hawai‘i’s corals are coping with the double threat of turbid water and rising ocean temperatures—stressors that are threatening reef health, especially along densely populated coasts.

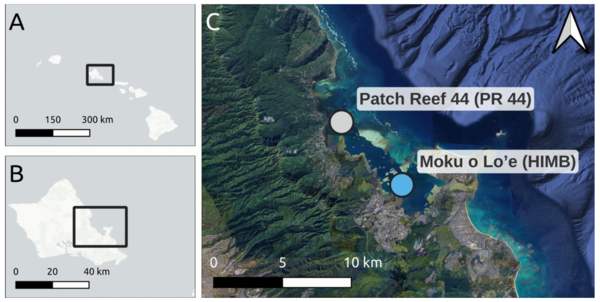

Coral reefs in places like Kāneʻohe Bay on Oʻahu already contend with sediment and pollution linked to urban development. These inputs cloud the water, reducing sunlight and depositing fine particles onto corals. Yet there is limited research on how coral species respond to these conditions—especially when combined with heat stress.

In the study, scientists tested how Montipora capitata, one of Hawai‘i’s dominant reef-building corals, reacts to different combinations of turbidity (cloudiness) and temperature. Corals were collected from two watersheds in Kāneʻohe Bay: a more polluted, poorly flushed southern region and a comparatively cleaner northern region.

In controlled experiments, the team exposed corals to a 12-hour burst of elevated turbidity, elevated temperature, or both at once, then measured respiration using intermittent-flow respirometry. The results revealed an important nuance: while the coral itself showed little immediate change under these stressful conditions, its algal symbionts—Symbiodinium, the microscopic partners that provide corals with most of their energy—responded quickly.

The researchers found that stress from cloudy water and heat disrupted the algae while the coral host remained stable, at least over the short exposure period. This suggests that the coral’s own physiological stress may lag behind that of its symbionts—a delay that could mask early warning signs of decline.

Location was also key. Corals from the more degraded southern Kāneʻohe Bay were noticeably more sensitive to combined stressors than those from the north, pointing to the role local watershed conditions play in shaping coral resilience. Poor water circulation and chronic urban impacts in the south appear to reduce coral resiliency to cope with l sudden bouts of heat or turbidity.

Although the short-term experiment did not show immediate effects on the coral host, the study warns that prolonged exposure likely would. Once the symbionts begin to falter, the coral becomes increasingly vulnerable to cascading physiological impacts such as reduced growth, lower reproductive success, or bleaching.

The findings underscore the need for place-based management. As global warming intensifies thermal stress and development increases turbidity, understanding how different coral populations respond is crucial for planning targeted restoration and protection strategies.