Oceanographic Instrumentation Detects Layers of Plankton Migration off Puerto Rico

Beneath the surface of the ocean, vast layers of planktonic life are constantly on the move—rising, sinking, spreading, and regrouping in response to light, predators, currents, and storms. This epic choreography is sometimes called the largest mass migration on earth, and it happens every day, out of our view.

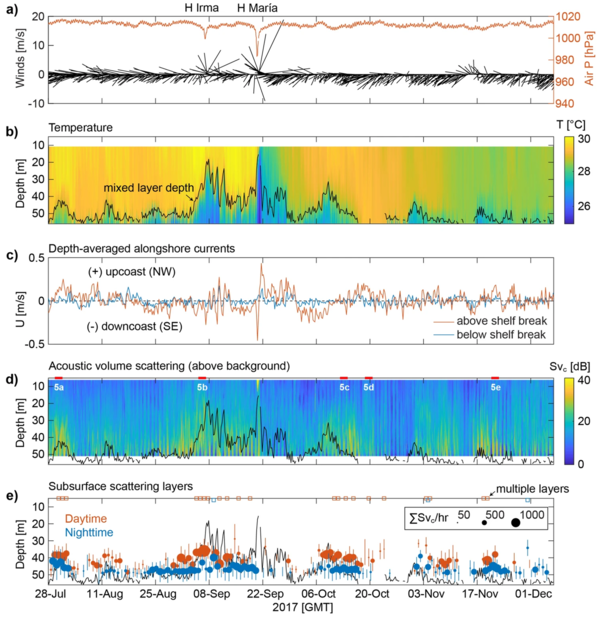

While scientists have long understood that these mass migrations of plankton occur, it is seldom that their movements are captured in detail. In new research led by USGS, scientists analyzed nearly five months of continuous, high-resolution oceanographic measurements collected above a mesophotic coral ecosystem (at depths of around 50 meters) on the upper insular slope off southwest Puerto Rico. The analysis revealed a distinct set of “sound scattering layers”—essentially dense aggregations of small particles that scatter sound—occurring daily and across seasons above the reef. These layers, detected using acoustic backscatter, are formed primarily by swarms of zooplankton, the tiny animals that form the base of many marine food webs.

The observations showed that zooplankton layers migrated vertically on daily cycles, sometimes following the familiar pattern of rising at night and sinking during the day, and other times doing the opposite. The layers could be thin—less than five meters thick—or split into multiple stacked layers. At times, internal waves pushed the layers up and down, while in other cases the zooplankton formed distinct layers even when the water column showed little temperature stratification.

Because the instruments were left in place for months, the study also captured how these dynamics changed with the seasons—and how they responded to extreme weather. Remarkably, the record spans the passage of two category-five hurricanes, Irma and María, providing a rare, high-resolution set of underwater ocean observations not detectable by more common surface observation platforms, such as buoys or satellites.

Zooplankton drifting through the water column provide energy to both sessile organisms, such as corals and sponges fixed to the seafloor, and mobile predators, including fish that move between depths. Their ability to migrate vertically links shallow shelves, upper slopes, and deeper mesophotic reefs, helping maintain trophic connectivity across the ecosystem.

“We found that the movement of these zooplankton layers is highly dynamic and finely structured, which would be difficult to capture with traditional net sampling or short-term surveys. Acoustic observation, by contrast, could continuously monitor this behavior in situ,” said USGS Oceanographer Olivia Cheriton, lead author of the study. “The ADCP [acoustic Doppler current profiler] was originally deployed to measure ocean currents over the insular slope. But one of my favorite parts about conducting research is that sometimes our measurements capture phenomena that we weren’t expecting to see.”

Read the study, Complex sound scattering layer and water-column dynamics over a mesophotic coral ecosystem: Southwest Puerto Rico, U.S.A, in Coral Reefs.