Long-term, Place-based, Science and Ecological Monitoring

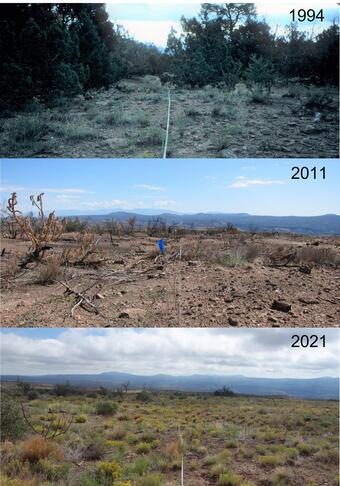

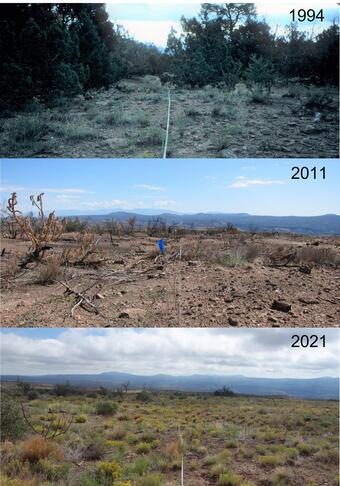

For over 30 years we have monitored the ecosystem dynamics of the mesas and mountains of northern New Mexico, co-located with mangers. We use a place-based science approach, defined as “science that is founded on long-term, repeated, field data and observations, as well as traditional knowledges, and regularly engages local managers and community members.” This approach enables us to provide land managers, scientists, and communities with diverse information on landscape responses to disturbances, such as fire, drought, and insect outbreaks. We measure changes in vegetation and erosion, forest demography and mortality, weekly tree growth, seed production, and detailed ecohydrological information. Many of these unique long-term data sets are part of broader research networks at regional, national, and global scales. Being co-located with our management partners, we are able to directly interpret ongoing research through high-quality, two-way, science-based conversations.

Adaptive, science-based land management—in which information on status and trends in an ecosystem is continually collected, analyzed, and communicated—is generally accepted as the desired approach for managing ecosystems on public lands, particularly in these times of rapid change. Such ecological knowledge is often time- and place-specific. If there are substantial knowledge gaps, land managers struggle to make sound science-based decisions. On the other hand, when scientists can interact onsite with managers regularly, effective communication, application, and follow-through of relevant science are greatly facilitated. This is where a place-based approach to science can help.

In its role as the scientific resource and advisor for Department of the Interior land management agencies, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) is fostering a place-based approach that co-locates some USGS researchers onsite and long-term with public land managers. Several are stationed in northern New Mexico, at the USGS Fort Collins Science Center's New Mexico Landscapes Field Station, where USGS scientists Ellis Margolis and Andreas Wion, and retired USGS scientist Craig Allen are co-located with National Park Service managers at Bandelier National Monument and Bureau of Land Management (BLM) managers in Santa Fe. These place-based USGS researchers routinely work with diverse local land managers to collaboratively develop, conduct, arrange, oversee, facilitate, and communicate about needed ecological research and monitoring, working to foster high-quality, science-based conversations on natural resource management issues among land managers as well as society at large.

The advantages of place-based scientists to land managers are many. Scientists like Margolis, Wion, and Allen act as a bridge between research and management, working to identify the information needs of management problems, secure external research funding, foster collaborations with outside institutions to conduct needed research, and communicate research findings quickly and effectively to local managers and the public. Place-based scientists develop substantial expertise in the ecology of their particular landscape. Eventually this allows them to become information brokers of the deep-rooted institutional knowledge that comes from being in a place long enough to learn its lessons and grow familiar with its natural and cultural rhythms and history.

While location in the same office and inclusion on the same working team with land managers is essential for integrating science and management, maintaining scientific impartiality and a degree of independence is also important. This is the unique opportunity afforded to USGS scientists, who are outside of the direct supervisory hierarchy of land management agencies, but can be located near or within various DOI public lands. These scientists can serve in the needed scientific advisory and coordination role, maintain scientific impartiality and independence, and also have access to the full range of science expertise and support services of the USGS. The result is a team effort that balances scientific objectivity with commitment and responsibility to management.

In addition, on-site science programs generate unique opportunities to conduct high-quality ecological research. The spectacular landscapes and special ecological circumstances of DOI land management units are a natural attraction for collaborative research with top-notch scientists and graduate students from academia and federal research centers—with place-based scientists present on-site to initiate, coordinate, and lead the research efforts. Indeed, the long-term, integrative, multidisciplinary datasets and research approaches that tend to emerge from place-focused research programs are increasingly recognized to be scientifically valuable at national and international scales. This impact occurs in part because such programs remain relatively scarce, and because the scientific work has demonstrable relevance to both local situations and pressing environmental issues of much broader application. In this way, place-based science can complement the valuable efforts of scientists in off-site research centers.

Good examples of on-site, place-based research programs are found at a number of National Park Service units, where individual USGS scientists have devoted major portions of their careers to working in particular landscapes (ranging from Glacier and Canyonlands to Sequoia and Redwoods national parks). Other agencies have also experimented with the idea, including the U.S. Forest Service. Such examples suggest that developing long-term, landscape-scale, on-site science programs could be a cost-effective way to meet critical information needs for many public land managers. Establishing additional place-based scientists could foster the development of land management organizations that institutionalize scientific approaches to learning, collaboration, open dialogue, and continual improvement—agencies that truly implement science-based adaptive management.

Below are other science projects associated with this project.

The New Mexico Landscapes Field Station

Below are publications associated with this project.

Vegetation type conversion in the US Southwest: Frontline observations and management responses Vegetation type conversion in the US Southwest: Frontline observations and management responses

Joint effects of climate, tree size, and year on annual tree growth derived using tree-ring records of ten globally distributed forests Joint effects of climate, tree size, and year on annual tree growth derived using tree-ring records of ten globally distributed forests

Tamm review: Postfire landscape management in frequent-fire conifer forests of the southwestern United States Tamm review: Postfire landscape management in frequent-fire conifer forests of the southwestern United States

Wildfire-driven forest conversion in western North American landscapes Wildfire-driven forest conversion in western North American landscapes

Limits to ponderosa pine regeneration following large high-severity forest fires in the United States Southwest Limits to ponderosa pine regeneration following large high-severity forest fires in the United States Southwest

Multi-scale predictions of massive conifer mortality due to chronic temperature rise Multi-scale predictions of massive conifer mortality due to chronic temperature rise

Larger trees suffer most during drought in forests worldwide Larger trees suffer most during drought in forests worldwide

Patterns and causes of observed piñon pine mortality in the southwestern United States Patterns and causes of observed piñon pine mortality in the southwestern United States

Unsupported inferences of high-severity fire in historical dry forests of the western United States: Response to Williams and Baker Unsupported inferences of high-severity fire in historical dry forests of the western United States: Response to Williams and Baker

An integrated model of environmental effects on growth, carbohydrate balance, and mortality of Pinus ponderosa forests in the southern Rocky Mountains An integrated model of environmental effects on growth, carbohydrate balance, and mortality of Pinus ponderosa forests in the southern Rocky Mountains

Temperature as a potent driver of regional forest drought stress and tree mortality Temperature as a potent driver of regional forest drought stress and tree mortality

The macroecology of sustainability The macroecology of sustainability

Below are partners associated with this project.

For over 30 years we have monitored the ecosystem dynamics of the mesas and mountains of northern New Mexico, co-located with mangers. We use a place-based science approach, defined as “science that is founded on long-term, repeated, field data and observations, as well as traditional knowledges, and regularly engages local managers and community members.” This approach enables us to provide land managers, scientists, and communities with diverse information on landscape responses to disturbances, such as fire, drought, and insect outbreaks. We measure changes in vegetation and erosion, forest demography and mortality, weekly tree growth, seed production, and detailed ecohydrological information. Many of these unique long-term data sets are part of broader research networks at regional, national, and global scales. Being co-located with our management partners, we are able to directly interpret ongoing research through high-quality, two-way, science-based conversations.

Adaptive, science-based land management—in which information on status and trends in an ecosystem is continually collected, analyzed, and communicated—is generally accepted as the desired approach for managing ecosystems on public lands, particularly in these times of rapid change. Such ecological knowledge is often time- and place-specific. If there are substantial knowledge gaps, land managers struggle to make sound science-based decisions. On the other hand, when scientists can interact onsite with managers regularly, effective communication, application, and follow-through of relevant science are greatly facilitated. This is where a place-based approach to science can help.

In its role as the scientific resource and advisor for Department of the Interior land management agencies, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) is fostering a place-based approach that co-locates some USGS researchers onsite and long-term with public land managers. Several are stationed in northern New Mexico, at the USGS Fort Collins Science Center's New Mexico Landscapes Field Station, where USGS scientists Ellis Margolis and Andreas Wion, and retired USGS scientist Craig Allen are co-located with National Park Service managers at Bandelier National Monument and Bureau of Land Management (BLM) managers in Santa Fe. These place-based USGS researchers routinely work with diverse local land managers to collaboratively develop, conduct, arrange, oversee, facilitate, and communicate about needed ecological research and monitoring, working to foster high-quality, science-based conversations on natural resource management issues among land managers as well as society at large.

The advantages of place-based scientists to land managers are many. Scientists like Margolis, Wion, and Allen act as a bridge between research and management, working to identify the information needs of management problems, secure external research funding, foster collaborations with outside institutions to conduct needed research, and communicate research findings quickly and effectively to local managers and the public. Place-based scientists develop substantial expertise in the ecology of their particular landscape. Eventually this allows them to become information brokers of the deep-rooted institutional knowledge that comes from being in a place long enough to learn its lessons and grow familiar with its natural and cultural rhythms and history.

While location in the same office and inclusion on the same working team with land managers is essential for integrating science and management, maintaining scientific impartiality and a degree of independence is also important. This is the unique opportunity afforded to USGS scientists, who are outside of the direct supervisory hierarchy of land management agencies, but can be located near or within various DOI public lands. These scientists can serve in the needed scientific advisory and coordination role, maintain scientific impartiality and independence, and also have access to the full range of science expertise and support services of the USGS. The result is a team effort that balances scientific objectivity with commitment and responsibility to management.

In addition, on-site science programs generate unique opportunities to conduct high-quality ecological research. The spectacular landscapes and special ecological circumstances of DOI land management units are a natural attraction for collaborative research with top-notch scientists and graduate students from academia and federal research centers—with place-based scientists present on-site to initiate, coordinate, and lead the research efforts. Indeed, the long-term, integrative, multidisciplinary datasets and research approaches that tend to emerge from place-focused research programs are increasingly recognized to be scientifically valuable at national and international scales. This impact occurs in part because such programs remain relatively scarce, and because the scientific work has demonstrable relevance to both local situations and pressing environmental issues of much broader application. In this way, place-based science can complement the valuable efforts of scientists in off-site research centers.

Good examples of on-site, place-based research programs are found at a number of National Park Service units, where individual USGS scientists have devoted major portions of their careers to working in particular landscapes (ranging from Glacier and Canyonlands to Sequoia and Redwoods national parks). Other agencies have also experimented with the idea, including the U.S. Forest Service. Such examples suggest that developing long-term, landscape-scale, on-site science programs could be a cost-effective way to meet critical information needs for many public land managers. Establishing additional place-based scientists could foster the development of land management organizations that institutionalize scientific approaches to learning, collaboration, open dialogue, and continual improvement—agencies that truly implement science-based adaptive management.

Below are other science projects associated with this project.

The New Mexico Landscapes Field Station

Below are publications associated with this project.

Vegetation type conversion in the US Southwest: Frontline observations and management responses Vegetation type conversion in the US Southwest: Frontline observations and management responses

Joint effects of climate, tree size, and year on annual tree growth derived using tree-ring records of ten globally distributed forests Joint effects of climate, tree size, and year on annual tree growth derived using tree-ring records of ten globally distributed forests

Tamm review: Postfire landscape management in frequent-fire conifer forests of the southwestern United States Tamm review: Postfire landscape management in frequent-fire conifer forests of the southwestern United States

Wildfire-driven forest conversion in western North American landscapes Wildfire-driven forest conversion in western North American landscapes

Limits to ponderosa pine regeneration following large high-severity forest fires in the United States Southwest Limits to ponderosa pine regeneration following large high-severity forest fires in the United States Southwest

Multi-scale predictions of massive conifer mortality due to chronic temperature rise Multi-scale predictions of massive conifer mortality due to chronic temperature rise

Larger trees suffer most during drought in forests worldwide Larger trees suffer most during drought in forests worldwide

Patterns and causes of observed piñon pine mortality in the southwestern United States Patterns and causes of observed piñon pine mortality in the southwestern United States

Unsupported inferences of high-severity fire in historical dry forests of the western United States: Response to Williams and Baker Unsupported inferences of high-severity fire in historical dry forests of the western United States: Response to Williams and Baker

An integrated model of environmental effects on growth, carbohydrate balance, and mortality of Pinus ponderosa forests in the southern Rocky Mountains An integrated model of environmental effects on growth, carbohydrate balance, and mortality of Pinus ponderosa forests in the southern Rocky Mountains

Temperature as a potent driver of regional forest drought stress and tree mortality Temperature as a potent driver of regional forest drought stress and tree mortality

The macroecology of sustainability The macroecology of sustainability

Below are partners associated with this project.