Where land meets sea: USGS science for resilient coastal habitats

USGS coastal science plays a critical role in supporting the effective, science-based management of coastal ecosystems, where the biodiversity of land and sea meet. It provides managers with the information they need to make sound decisions. Through cutting-edge research, predictive modeling, and decision-support tools, USGS empowers resource managers to make informed, science-based choices. From understanding habitat shifts under increasingly more powerful storms and extreme weather, USGS science translates complex data into actionable strategies for coastal stewardship.

Dive into our current coastal projects, learn more about coastal and nearshore ecosystems, search our publications, and connect.

Snapshot of what we're working on

Our work helps to support coastal resiliency along U.S. shorelines. We research coastal and nearshore processes such as habitat change, storm impacts, erosion, and ecosystem structure and function using mapping and monitoring, and other techniques to understand coastal habitats.

Decision science

Klamath Dam Removal

Wetlands

Oysters

Coastal and nearshore ecosystems

Coastal ecosystems are dynamic zones where land, freshwater, and ocean processes intersect. Integrating ecosystem and species restoration—considering both habitat quality and quantity—into fish and wildlife management plans helps sustain productivity and population stability over the long term.

Evaluating the success of ecosystem management often focuses on the presence or absence of short-term indicators (e.g., species or habitat components), but what if we also included the impact on the ecological systems and cycles that support the species?

To achieve lasting species persistence, including key aspects of ecosystem structure and function in management goals may improve fish and wildlife outcomes.

Coastal ecosystems are naturally resilient

Coastal ecosystems occur at the interface between terrestrial and marine systems, and serve as critical transition zones for the life history stages of anadromous and estuarine-dependent fish species, as well as many migratory birds, marine mammals, and other coastal-dependent wildlife. Though coastal ecosystems evolved with natural disturbances (e.g., hurricanes), they are also exposed to a range of human-caused stressors. Normally, an ecosystem demonstrates resilience and returns to its usual functions (e.g., nutrient cycling, hydrology) after exposure to a stressor.

However, repeated exposure to stressors can ultimately impact those ecosystem functions. When one or more ecosystem functions are degraded, the system’s ability to recover (i.e., return to previous conditions) from future stresses diminishes. In other words, after too much stress, the ecosystem becomes less resilient to future stressors.

Global stressors

Ocean warming and sea-level rise alter temperature regimes and inundation patterns.

Distant land-based drivers

Glacial melt, rainstorms, and droughts influence freshwater inputs and sediment delivery. Human modifications, including gravel mining and dams, can restrict the sediment transport needed for maintaining delta and estuarine habitats.

Local impacts

Urbanization, dredging, shoreline hardening (e.g., levees, seawalls), and oil spills can eliminate spawning habitat for forage fish, alter juvenile salmon rearing areas, reduce nesting and foraging sites for coastal birds, and disrupt benthic prey communities for groundfish, shellfish, and wading birds.

Ecosystem structure and function

Ecosystems are more than a static collection of plants and animals. An ecosystem is a dynamic set of processes that supports species and with which species interact. Ecosystems don’t just have structures; they have functions. For fish and wildlife, these functions are necessary for recruitment, survival, movement, and long-term population productivity.

Ecosystem structure

The physical configuration created by the presence and interactions between the biotic (e.g., plants, animals) and abiotic (e.g., soil, water, minerals) components of an ecosystem.

Ecosystem function

Ecosystem functions are the processes and interactions that occur within or between ecosystems. A food web is an ecosystem function that supports species. Protection from predators can also be an ecosystem function. For example, saltwater marshes can function as nurseries for juvenile marine fish by protecting the small fish from larger predators. They also provide critical foraging and roosting habitat for shorebirds and waterfowl, supporting commercially important species such as blue crab and striped bass, as well as wildlife populations important for recreation, subsistence, and ecosystem health. The same salt marshes perform a function for humans by protecting juvenile fish that grow up to be available for commercial harvest.

Examples of ecosystem structures and functions that support biodiversity

Examples of ecosystem structures and functions that support biodiversity include those that promote species survival. Examples include tidal marshes and seagrass beds, which provide nursery habitats for young fish, and coral reefs which provide hiding places for small fish and food sources for larger fish. These structures and functions are essential for maintaining resilient ecosystems capable of persisting under stress. Fortunately for humans, all three ecosystems buffer shorelines from wave energy.

Restoring connectivity

Barriers to the movement of anadromous fish also limit the transfer of nutrients from the marine to the freshwater system, which starves the freshwater food web and is associated with salmonid population declines (LeRoy et al. 2017). Barrier removal projects have increased populations of river herring and salmon and have restored access by wildlife such as beavers and waterfowl to connected floodplains.

Enhancing water quality

Demonstrating the ecological benefits of nature's ecosystem engineers, Bason et al. (2017) reported that water downstream of beaver ponds in rural Coastal Plains of the Southeastern U.S. had reduced concentrations of nitrates and suspended sediments compared to those not associated with beaver ponds. This improvement benefits fish by increasing dissolved oxygen levels and reducing egg-smothering sediments, while also supporting healthier wetland vegetation and invertebrate communities that sustain amphibians, reptiles, and birds.

Including diverse habitats

Maintaining a mosaic of habitat types and physical variation (e.g., pond depth) within an ecosystem can support a diverse bird community (De La Cruz et al. 2018).

How coastal ecosystems support fish and wildlife

Many species of plants and animals are found only in coastal ecosystems. These include species limited to the coast, such as the salt marsh harvest mouse (Reithrodontomys raviventris) and the Florida salt marsh vole (Microtus pennsylvanicus dukecampbelli; Thorne et al. 2012).

Red mangroves

Highlighting coral resilience, Rogers and Herlan (2012) reported that stony corals off the coast of St. John, US Virgin Islands, growing under the prop roots of red mangroves (Rhizophora mangle) experienced cooler microclimates than those in the open ocean. These sheltered corals avoided the bleaching and disease outbreaks that affected corals in the open ocean.

Where land meets sea

Some species primarily associated with terrestrial or marine environments rely on access to coastal habitats to enhance their survival.

Chinook salmon

Chinook salmon (Onchorhynchis tshawytscha) rely on a mix of habitat types throughout their lifecycle, such as brackish marshes, freshwater marshes, and tidal forests (Moritschet al. 2022; Ruben et al. 2024). In the Nisqually River Delta (Southern Puget Sound), Davis et al. (2019) found that the amount of prey for Chinook salmon was 46–86% higher in tidal forests than in any other habitat type. This multi-habitat reliance mirrors the needs of other anadromous fish, such as American shad and alewife, and of wildlife species such as river otters and ospreys that depend on healthy fish populations.

Water temperature

Water temperature is critical for fish, which are ectothermic, but it varies among coastal ecosystems. It tends to be cooler in beaver ponds and warmer in coastal mudflat channels (Thorne et al. 2012; Davis et al. 2022). Whether warmer or cooler water is more beneficial depends on the local thermal regime and the physiological needs of fish in a specific location.

Terrestrial, coastal, and marine systems are interconnected, and the flow of energy and nutrients among them—also known as resource subsidies—supports biodiversity

When salmon return to their natal rivers to spawn and die, they transfer energy (i.e., calories) and nutrients (e.g., nitrogen and phosphorus) from the ocean into terrestrial and freshwater systems. These nutrient subsidies support mammals such as grizzly and black bears (Ursus spp.), wolves (Canis lupus), coyotes (Canis latrans), American mink (Neogale vison), and avian scavengers such as bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) and ravens (Corvus corax).

Changes to sediment movement (e.g., following dam removal) or the plant community can alter the composition of “litter”, which can in-turn affect the invertebrate community—the primary food source for many fish (Thorne et al. 2012; LeRoy et al. 2023).

USGS science to support restoration and management

Effective natural resource management depends on understanding how the resilience and function of estuarine habitats respond to both management actions and long-term stressors such as sea-level rise (Enwright et al. 2016; Osland et al. 2022; Thorne et al. 2025). For fish and wildlife, this means linking long-term species viability to habitat resilience, harvest levels, and recovery targets. Restoration efforts often focus on species-specific outcomes (e.g., population density or richness), but Bellmore et al. (2017) emphasize the importance of also restoring ecosystem functions, such as food webs, needed to support species for long-term success.

Mangrove restoration in the Caribbean

Mangroves provide a nursery habitat for high-value reef fish, such as snapper and grouper, as well as nesting and shelter for birds, reptiles, and invertebrates. Krauss et al. (2023) describe how trying to restore the different types of mangrove forests in the Caribbean by exclusively planting mangrove seedlings will fail if preexisting damage to the ecosystem functions (e.g., tidal flushing, sediment transport, seed movement) necessary for mangrove forest regeneration and persistence is not improved.

Using models to prioritize restoration focus

These tools can be adapted to optimize restoration outcomes for fish and wildlife by balancing commercial, recreational, cultural, and conservation objectives. Peterson and Duarte (2024) used an existing fall-run Chinook salmon decision-support model to evaluate under which conditions the restoration of floodplains or channel habitat would provide the greatest benefits to that salmon population.

Modeling ecosystem functions to guide decision-making

Ecosystem models are powerful tools for conceptually linking coastal habitat functions to species outcomes. For fish and wildlife managers, nutrient–energy flow models can inform escapement (fish return) goals, habitat enhancement priorities, optimal harvest timing, and conservation strategies for at-risk species. One approach involves modeling ecological processes using a common currency (e.g., energy or nutrients) that allows managers and decision-makers to evaluate how management actions impact species and ecosystems simultaneously. For example, conceptual mechanistic models of nutrient and energy exchange across terrestrial, freshwater, and marine systems can inform restoration planning by identifying where and how interventions may be most effective.

Decision support

Building on recent advancements in decision-making, Peterson et al. (2024) illustrated how to develop and use ecological models linked to management objectives (i.e., decision support model) to evaluate trade-offs among possible actions within a structured decision-making framework (Smith et al. 2020).

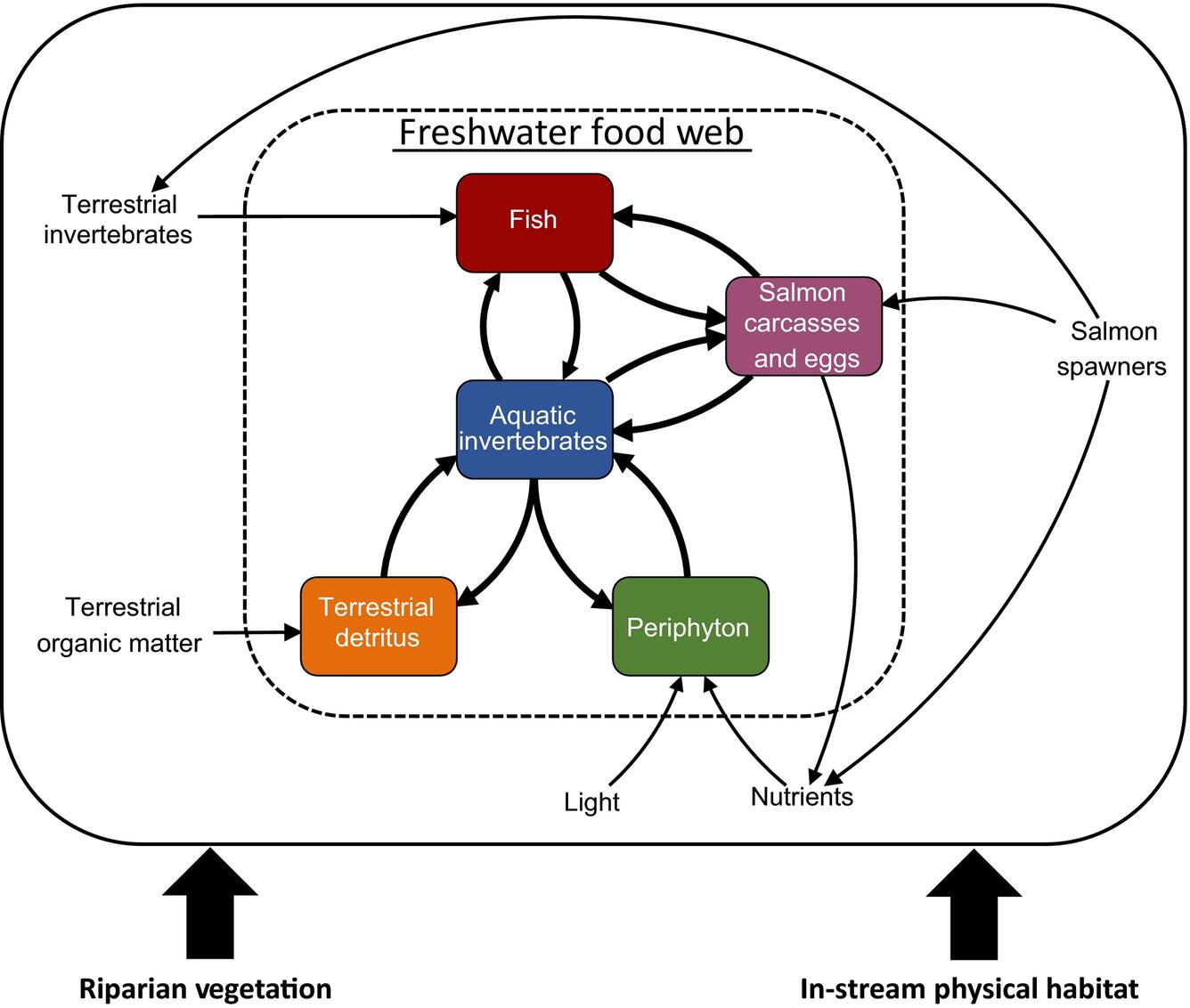

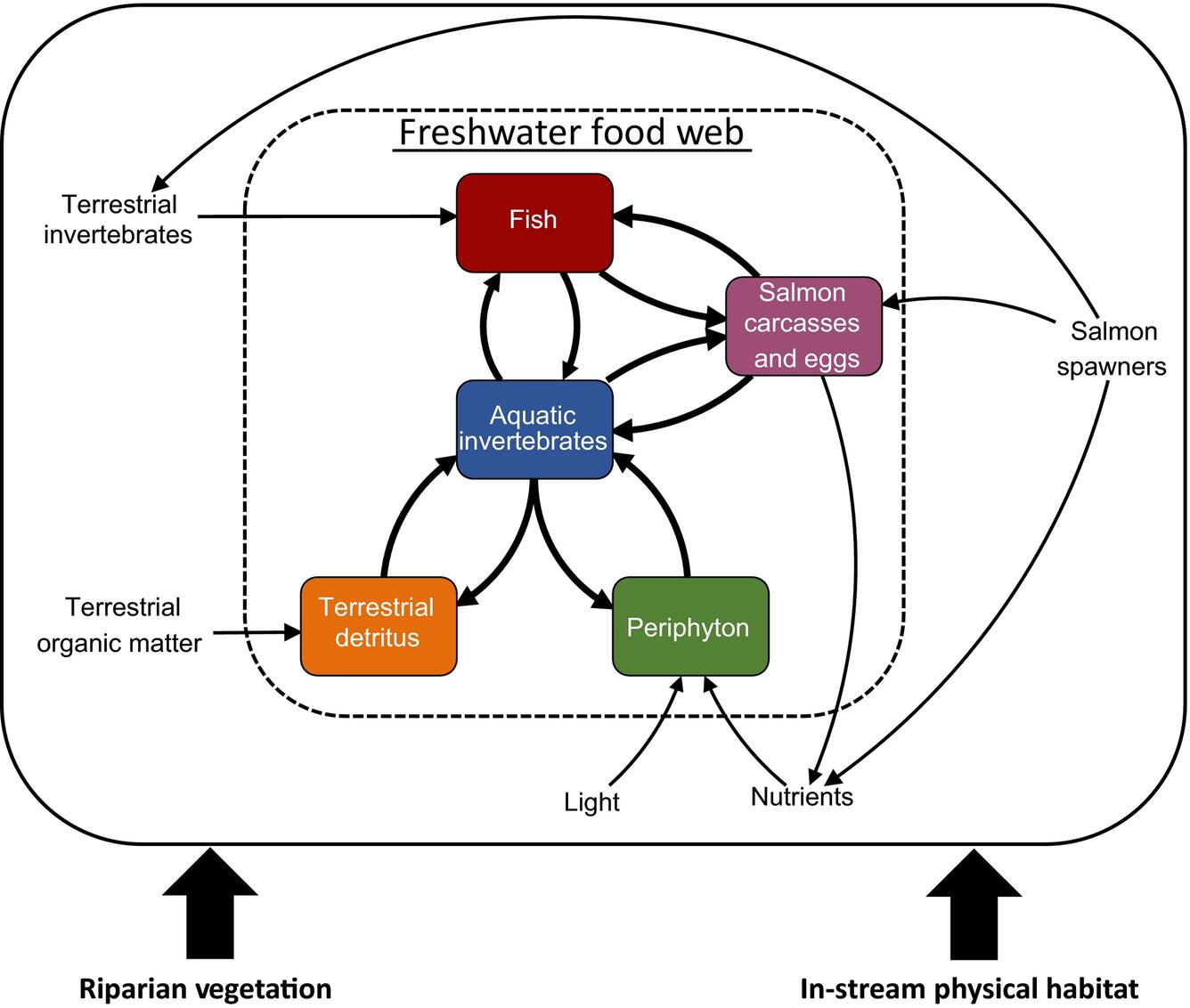

Freshwater food web (Bellmore et al., 2017)

Models can be used to demonstrate the potential outcomes of different restoration scenarios, such as the relative benefits of additional restoration costs (e.g., side channel restoration), or where the system’s function (e.g., the capacity to support native fish) is most sensitive to variation (e.g., food web structure). Bellmore et al. (2017) modeled different river restoration scenarios with different food web configurations on potential native fish targets.

Examples of USGS ecological research to improve conceptual models

USGS coastal science helps managers make complex decisions by improving models that underpin resource management. Through ecological research, USGS refines our understanding of how coastal systems respond to stressors like sea-level rise, climate, habitat fragmentation, fish passage, salt marsh and mangrove research, energy flow studies, and climate resilience assessments, as well as management actions like dam removal (Perry et al. 2023).

Improving fish habitat

Management actions that improve or restore terrestrial-aquatic linkages can enhance the influx of nutrients which supports prey populations in estuaries. Davis et al. (2024) reported that juvenile salmon derived their energy from a mix of terrestrial, pelagic, and benthic prey, including insects, flies, and crustaceans. Smith et al. (2022) reported from simulations of sea level rise along coastal Washington that in coming years, there could be less spawning habitat for surf smelt (Hypomesus pretiosus), but more eel grass (Zostera marina L).

Imperiled species in the southeastern U.S.

Many actions that are designed for human communities, such as the construction of flood levees and dikes, could be modified to also protect biodiversity. Walls et al. (2019) and Koen et al. (2025) lay the groundwork for a stronger focus on strategic planning for imperiled species in Southeastern U.S. coastal systems (e.g., Key Deer, Odocoileus virginianus clavium; Cedar Key Mole Skink, Plestiodon egregius insularis), which face the increasing threat of catastrophic hurricanes.

Fish passage

Obstructions to the movement of fish between rivers and marine spawning sites are associated with population declines. Improved passage design benefits native fish conservation and helps sustain mixed-stock fisheries, while also maintaining connectivity for semi-aquatic wildlife such as turtles, otters, and amphibians. Instream structures such as tide and flood gates, road crossings, and small irrigation dams not designed, installed, and maintained correctly can slow or stop fish from moving among necessary habitats throughout the year and facilitate genetic diversity. Benoit et al. (2025) designed a framework for designing selective fish passages in a diverse fish community, such as in the Great Lakes. Ahmad et al. (2025) present a novel approach for quantifying the hydrologic connectivity of floodplain lakes to streams.

Linking ecosystem and species restoration

Linking ecosystem and species restoration, including both habitat quality and quantity considerations in fish and wildlife management plans, ensures that productivity gains and population stability are sustained for decades.

Ecosystem management

Ecosystem management frequently focuses on the short-term response by the ecosystem (i.e., presence/absence of ecosystem components) and the target species (e.g., presence/absence).

Management interventions

Management interventions often influence the ecological systems upon which those species also depend for their life histories.

Ecosystem structure

USGS science reveals the many relationships between robust ecosystem structure and function and the goals of species persistence.

Interrelated elements of ecosystem and species science

USGS coastal science helps to inform coastal species management by:

- Providing predictive models of habitat change under sea-level rise.

- Quantifying energy and nutrient flows that underpin biodiversity.

- Assessing the impact of structural barriers and restoration actions on fish movement.

- Identifying habitat types that confer climate resilience to wildlife.

- Designing long-term models that align with management objectives.

- Working with partners through a decision analysis framework to foster inter-agency communication and collaboration when working on management problems containing competing objectives and stakeholder values.

- USGS predictive models which can be integrated into fish and wildlife management plans at state, tribal, and federal levels.

- Using USGS barrier assessment data to target high-impact passage and connectivity projects for both aquatic and terrestrial species.

- Availability of USGS weather resilience mapping to inform place-based decisions.

- Linking restoration outcomes to measurable increases in fishery productivity, wildlife population health, and ecosystem function.

Nature-based solutions could offset coastal squeeze of tidal wetlands from sea-level rise on the U.S. Pacific coast Nature-based solutions could offset coastal squeeze of tidal wetlands from sea-level rise on the U.S. Pacific coast

Designing sortable guilds for multispecies selective fish passage Designing sortable guilds for multispecies selective fish passage

Confluence of time and space: An innovation for quantifying dynamics of hydrologic floodplain connectivity with remote sensing and GIS Confluence of time and space: An innovation for quantifying dynamics of hydrologic floodplain connectivity with remote sensing and GIS

Sea level rise threatens Florida’s insular vertebrate biodiversity Sea level rise threatens Florida’s insular vertebrate biodiversity

An evaluation of tradeoffs in restoring ephemeral vs. perennial habitats to conserve animal populations An evaluation of tradeoffs in restoring ephemeral vs. perennial habitats to conserve animal populations

Benthic macroinvertebrate response to estuarine emergent marsh restoration across a delta-wide environmental gradient Benthic macroinvertebrate response to estuarine emergent marsh restoration across a delta-wide environmental gradient

Prototyping structured decision making for water resource management in the San Francisco Bay-Delta Prototyping structured decision making for water resource management in the San Francisco Bay-Delta

Allochthonous marsh subsidies enhances food web productivity in an estuary and its surrounding ecosystem mosaic Allochthonous marsh subsidies enhances food web productivity in an estuary and its surrounding ecosystem mosaic

Leaf litter decomposition and detrital communities following the removal of two large dams on the Elwha River (Washington, USA) Leaf litter decomposition and detrital communities following the removal of two large dams on the Elwha River (Washington, USA)

Coastal vegetation responses to large dam removal on the Elwha River Coastal vegetation responses to large dam removal on the Elwha River

Framework for facilitating mangrove recovery after hurricanes on Caribbean islands Framework for facilitating mangrove recovery after hurricanes on Caribbean islands

Migration and transformation of coastal wetlands in response to rising seas Migration and transformation of coastal wetlands in response to rising seas

Western Ecological Research Center - Headquarters Western Ecological Research Center - Headquarters

3020 State University Drive

Modoc Hall, Room 4004

Sacramento, CA 95819

United States

Wetland and Aquatic Research Center - Gainesville, FL Wetland and Aquatic Research Center - Gainesville, FL

7920 NW 71st St.

Gainesville, FL 32653

United States

Cooperative Research Units Program Cooperative Research Units Program

12201 Sunrise Valley Dr

Reston, VA 20192

United States

Sacramento Projects Office (USGS California Water Science Center) Sacramento Projects Office (USGS California Water Science Center)

6000 J Street, Placer Hall

Sacramento, CA 95819

United States

Western Fisheries Research Center (WFRC) Western Fisheries Research Center (WFRC)

6505 NE 65th Street

Seattle, WA 98115-5016

United States

Forest and Rangeland Ecosystem Science Center (FRESC) Headquarters Forest and Rangeland Ecosystem Science Center (FRESC) Headquarters

3200 SW Jefferson Way

Suite 400

Corvallis, OR 97331

United States

Land Change Science Program, USGS Ecosystems Mission Area Land Change Science Program, USGS Ecosystems Mission Area

12201 Sunrise Valley Drive

Reston, VA 20192

United States

Lower Mississippi-Gulf Water Science Center - Baton Rouge, LA Office Lower Mississippi-Gulf Water Science Center - Baton Rouge, LA Office

3535 South Sherwood Forest Blvd.

Suite 120

Baton Rouge, LA 70816

United States

Pacific Coastal and Marine Science Center Pacific Coastal and Marine Science Center

2885 Mission Street

Santa Cruz, CA 95060

United States

Science and Decisions Center Science and Decisions Center

12201 Sunrise Valley Drive

Mail Stop 913

Reston, VA 20192

United States

Western Geographic Science Center - Main Office Western Geographic Science Center - Main Office

350 N. Akron Rd.

Moffett Field, CA 94035

United States

USGS coastal science plays a critical role in supporting the effective, science-based management of coastal ecosystems, where the biodiversity of land and sea meet. It provides managers with the information they need to make sound decisions. Through cutting-edge research, predictive modeling, and decision-support tools, USGS empowers resource managers to make informed, science-based choices. From understanding habitat shifts under increasingly more powerful storms and extreme weather, USGS science translates complex data into actionable strategies for coastal stewardship.

Dive into our current coastal projects, learn more about coastal and nearshore ecosystems, search our publications, and connect.

Snapshot of what we're working on

Our work helps to support coastal resiliency along U.S. shorelines. We research coastal and nearshore processes such as habitat change, storm impacts, erosion, and ecosystem structure and function using mapping and monitoring, and other techniques to understand coastal habitats.

Decision science

Klamath Dam Removal

Wetlands

Oysters

Coastal and nearshore ecosystems

Coastal ecosystems are dynamic zones where land, freshwater, and ocean processes intersect. Integrating ecosystem and species restoration—considering both habitat quality and quantity—into fish and wildlife management plans helps sustain productivity and population stability over the long term.

Evaluating the success of ecosystem management often focuses on the presence or absence of short-term indicators (e.g., species or habitat components), but what if we also included the impact on the ecological systems and cycles that support the species?

To achieve lasting species persistence, including key aspects of ecosystem structure and function in management goals may improve fish and wildlife outcomes.

Coastal ecosystems are naturally resilient

Coastal ecosystems occur at the interface between terrestrial and marine systems, and serve as critical transition zones for the life history stages of anadromous and estuarine-dependent fish species, as well as many migratory birds, marine mammals, and other coastal-dependent wildlife. Though coastal ecosystems evolved with natural disturbances (e.g., hurricanes), they are also exposed to a range of human-caused stressors. Normally, an ecosystem demonstrates resilience and returns to its usual functions (e.g., nutrient cycling, hydrology) after exposure to a stressor.

However, repeated exposure to stressors can ultimately impact those ecosystem functions. When one or more ecosystem functions are degraded, the system’s ability to recover (i.e., return to previous conditions) from future stresses diminishes. In other words, after too much stress, the ecosystem becomes less resilient to future stressors.

Global stressors

Ocean warming and sea-level rise alter temperature regimes and inundation patterns.

Distant land-based drivers

Glacial melt, rainstorms, and droughts influence freshwater inputs and sediment delivery. Human modifications, including gravel mining and dams, can restrict the sediment transport needed for maintaining delta and estuarine habitats.

Local impacts

Urbanization, dredging, shoreline hardening (e.g., levees, seawalls), and oil spills can eliminate spawning habitat for forage fish, alter juvenile salmon rearing areas, reduce nesting and foraging sites for coastal birds, and disrupt benthic prey communities for groundfish, shellfish, and wading birds.

Ecosystem structure and function

Ecosystems are more than a static collection of plants and animals. An ecosystem is a dynamic set of processes that supports species and with which species interact. Ecosystems don’t just have structures; they have functions. For fish and wildlife, these functions are necessary for recruitment, survival, movement, and long-term population productivity.

Ecosystem structure

The physical configuration created by the presence and interactions between the biotic (e.g., plants, animals) and abiotic (e.g., soil, water, minerals) components of an ecosystem.

Ecosystem function

Ecosystem functions are the processes and interactions that occur within or between ecosystems. A food web is an ecosystem function that supports species. Protection from predators can also be an ecosystem function. For example, saltwater marshes can function as nurseries for juvenile marine fish by protecting the small fish from larger predators. They also provide critical foraging and roosting habitat for shorebirds and waterfowl, supporting commercially important species such as blue crab and striped bass, as well as wildlife populations important for recreation, subsistence, and ecosystem health. The same salt marshes perform a function for humans by protecting juvenile fish that grow up to be available for commercial harvest.

Examples of ecosystem structures and functions that support biodiversity

Examples of ecosystem structures and functions that support biodiversity include those that promote species survival. Examples include tidal marshes and seagrass beds, which provide nursery habitats for young fish, and coral reefs which provide hiding places for small fish and food sources for larger fish. These structures and functions are essential for maintaining resilient ecosystems capable of persisting under stress. Fortunately for humans, all three ecosystems buffer shorelines from wave energy.

Restoring connectivity

Barriers to the movement of anadromous fish also limit the transfer of nutrients from the marine to the freshwater system, which starves the freshwater food web and is associated with salmonid population declines (LeRoy et al. 2017). Barrier removal projects have increased populations of river herring and salmon and have restored access by wildlife such as beavers and waterfowl to connected floodplains.

Enhancing water quality

Demonstrating the ecological benefits of nature's ecosystem engineers, Bason et al. (2017) reported that water downstream of beaver ponds in rural Coastal Plains of the Southeastern U.S. had reduced concentrations of nitrates and suspended sediments compared to those not associated with beaver ponds. This improvement benefits fish by increasing dissolved oxygen levels and reducing egg-smothering sediments, while also supporting healthier wetland vegetation and invertebrate communities that sustain amphibians, reptiles, and birds.

Including diverse habitats

Maintaining a mosaic of habitat types and physical variation (e.g., pond depth) within an ecosystem can support a diverse bird community (De La Cruz et al. 2018).

How coastal ecosystems support fish and wildlife

Many species of plants and animals are found only in coastal ecosystems. These include species limited to the coast, such as the salt marsh harvest mouse (Reithrodontomys raviventris) and the Florida salt marsh vole (Microtus pennsylvanicus dukecampbelli; Thorne et al. 2012).

Red mangroves

Highlighting coral resilience, Rogers and Herlan (2012) reported that stony corals off the coast of St. John, US Virgin Islands, growing under the prop roots of red mangroves (Rhizophora mangle) experienced cooler microclimates than those in the open ocean. These sheltered corals avoided the bleaching and disease outbreaks that affected corals in the open ocean.

Where land meets sea

Some species primarily associated with terrestrial or marine environments rely on access to coastal habitats to enhance their survival.

Chinook salmon

Chinook salmon (Onchorhynchis tshawytscha) rely on a mix of habitat types throughout their lifecycle, such as brackish marshes, freshwater marshes, and tidal forests (Moritschet al. 2022; Ruben et al. 2024). In the Nisqually River Delta (Southern Puget Sound), Davis et al. (2019) found that the amount of prey for Chinook salmon was 46–86% higher in tidal forests than in any other habitat type. This multi-habitat reliance mirrors the needs of other anadromous fish, such as American shad and alewife, and of wildlife species such as river otters and ospreys that depend on healthy fish populations.

Water temperature

Water temperature is critical for fish, which are ectothermic, but it varies among coastal ecosystems. It tends to be cooler in beaver ponds and warmer in coastal mudflat channels (Thorne et al. 2012; Davis et al. 2022). Whether warmer or cooler water is more beneficial depends on the local thermal regime and the physiological needs of fish in a specific location.

Terrestrial, coastal, and marine systems are interconnected, and the flow of energy and nutrients among them—also known as resource subsidies—supports biodiversity

When salmon return to their natal rivers to spawn and die, they transfer energy (i.e., calories) and nutrients (e.g., nitrogen and phosphorus) from the ocean into terrestrial and freshwater systems. These nutrient subsidies support mammals such as grizzly and black bears (Ursus spp.), wolves (Canis lupus), coyotes (Canis latrans), American mink (Neogale vison), and avian scavengers such as bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) and ravens (Corvus corax).

Changes to sediment movement (e.g., following dam removal) or the plant community can alter the composition of “litter”, which can in-turn affect the invertebrate community—the primary food source for many fish (Thorne et al. 2012; LeRoy et al. 2023).

USGS science to support restoration and management

Effective natural resource management depends on understanding how the resilience and function of estuarine habitats respond to both management actions and long-term stressors such as sea-level rise (Enwright et al. 2016; Osland et al. 2022; Thorne et al. 2025). For fish and wildlife, this means linking long-term species viability to habitat resilience, harvest levels, and recovery targets. Restoration efforts often focus on species-specific outcomes (e.g., population density or richness), but Bellmore et al. (2017) emphasize the importance of also restoring ecosystem functions, such as food webs, needed to support species for long-term success.

Mangrove restoration in the Caribbean

Mangroves provide a nursery habitat for high-value reef fish, such as snapper and grouper, as well as nesting and shelter for birds, reptiles, and invertebrates. Krauss et al. (2023) describe how trying to restore the different types of mangrove forests in the Caribbean by exclusively planting mangrove seedlings will fail if preexisting damage to the ecosystem functions (e.g., tidal flushing, sediment transport, seed movement) necessary for mangrove forest regeneration and persistence is not improved.

Using models to prioritize restoration focus

These tools can be adapted to optimize restoration outcomes for fish and wildlife by balancing commercial, recreational, cultural, and conservation objectives. Peterson and Duarte (2024) used an existing fall-run Chinook salmon decision-support model to evaluate under which conditions the restoration of floodplains or channel habitat would provide the greatest benefits to that salmon population.

Modeling ecosystem functions to guide decision-making

Ecosystem models are powerful tools for conceptually linking coastal habitat functions to species outcomes. For fish and wildlife managers, nutrient–energy flow models can inform escapement (fish return) goals, habitat enhancement priorities, optimal harvest timing, and conservation strategies for at-risk species. One approach involves modeling ecological processes using a common currency (e.g., energy or nutrients) that allows managers and decision-makers to evaluate how management actions impact species and ecosystems simultaneously. For example, conceptual mechanistic models of nutrient and energy exchange across terrestrial, freshwater, and marine systems can inform restoration planning by identifying where and how interventions may be most effective.

Decision support

Building on recent advancements in decision-making, Peterson et al. (2024) illustrated how to develop and use ecological models linked to management objectives (i.e., decision support model) to evaluate trade-offs among possible actions within a structured decision-making framework (Smith et al. 2020).

Freshwater food web (Bellmore et al., 2017)

Models can be used to demonstrate the potential outcomes of different restoration scenarios, such as the relative benefits of additional restoration costs (e.g., side channel restoration), or where the system’s function (e.g., the capacity to support native fish) is most sensitive to variation (e.g., food web structure). Bellmore et al. (2017) modeled different river restoration scenarios with different food web configurations on potential native fish targets.

Examples of USGS ecological research to improve conceptual models

USGS coastal science helps managers make complex decisions by improving models that underpin resource management. Through ecological research, USGS refines our understanding of how coastal systems respond to stressors like sea-level rise, climate, habitat fragmentation, fish passage, salt marsh and mangrove research, energy flow studies, and climate resilience assessments, as well as management actions like dam removal (Perry et al. 2023).

Improving fish habitat

Management actions that improve or restore terrestrial-aquatic linkages can enhance the influx of nutrients which supports prey populations in estuaries. Davis et al. (2024) reported that juvenile salmon derived their energy from a mix of terrestrial, pelagic, and benthic prey, including insects, flies, and crustaceans. Smith et al. (2022) reported from simulations of sea level rise along coastal Washington that in coming years, there could be less spawning habitat for surf smelt (Hypomesus pretiosus), but more eel grass (Zostera marina L).

Imperiled species in the southeastern U.S.

Many actions that are designed for human communities, such as the construction of flood levees and dikes, could be modified to also protect biodiversity. Walls et al. (2019) and Koen et al. (2025) lay the groundwork for a stronger focus on strategic planning for imperiled species in Southeastern U.S. coastal systems (e.g., Key Deer, Odocoileus virginianus clavium; Cedar Key Mole Skink, Plestiodon egregius insularis), which face the increasing threat of catastrophic hurricanes.

Fish passage

Obstructions to the movement of fish between rivers and marine spawning sites are associated with population declines. Improved passage design benefits native fish conservation and helps sustain mixed-stock fisheries, while also maintaining connectivity for semi-aquatic wildlife such as turtles, otters, and amphibians. Instream structures such as tide and flood gates, road crossings, and small irrigation dams not designed, installed, and maintained correctly can slow or stop fish from moving among necessary habitats throughout the year and facilitate genetic diversity. Benoit et al. (2025) designed a framework for designing selective fish passages in a diverse fish community, such as in the Great Lakes. Ahmad et al. (2025) present a novel approach for quantifying the hydrologic connectivity of floodplain lakes to streams.

Linking ecosystem and species restoration

Linking ecosystem and species restoration, including both habitat quality and quantity considerations in fish and wildlife management plans, ensures that productivity gains and population stability are sustained for decades.

Ecosystem management

Ecosystem management frequently focuses on the short-term response by the ecosystem (i.e., presence/absence of ecosystem components) and the target species (e.g., presence/absence).

Management interventions

Management interventions often influence the ecological systems upon which those species also depend for their life histories.

Ecosystem structure

USGS science reveals the many relationships between robust ecosystem structure and function and the goals of species persistence.

Interrelated elements of ecosystem and species science

USGS coastal science helps to inform coastal species management by:

- Providing predictive models of habitat change under sea-level rise.

- Quantifying energy and nutrient flows that underpin biodiversity.

- Assessing the impact of structural barriers and restoration actions on fish movement.

- Identifying habitat types that confer climate resilience to wildlife.

- Designing long-term models that align with management objectives.

- Working with partners through a decision analysis framework to foster inter-agency communication and collaboration when working on management problems containing competing objectives and stakeholder values.

- USGS predictive models which can be integrated into fish and wildlife management plans at state, tribal, and federal levels.

- Using USGS barrier assessment data to target high-impact passage and connectivity projects for both aquatic and terrestrial species.

- Availability of USGS weather resilience mapping to inform place-based decisions.

- Linking restoration outcomes to measurable increases in fishery productivity, wildlife population health, and ecosystem function.

Nature-based solutions could offset coastal squeeze of tidal wetlands from sea-level rise on the U.S. Pacific coast Nature-based solutions could offset coastal squeeze of tidal wetlands from sea-level rise on the U.S. Pacific coast

Designing sortable guilds for multispecies selective fish passage Designing sortable guilds for multispecies selective fish passage

Confluence of time and space: An innovation for quantifying dynamics of hydrologic floodplain connectivity with remote sensing and GIS Confluence of time and space: An innovation for quantifying dynamics of hydrologic floodplain connectivity with remote sensing and GIS

Sea level rise threatens Florida’s insular vertebrate biodiversity Sea level rise threatens Florida’s insular vertebrate biodiversity

An evaluation of tradeoffs in restoring ephemeral vs. perennial habitats to conserve animal populations An evaluation of tradeoffs in restoring ephemeral vs. perennial habitats to conserve animal populations

Benthic macroinvertebrate response to estuarine emergent marsh restoration across a delta-wide environmental gradient Benthic macroinvertebrate response to estuarine emergent marsh restoration across a delta-wide environmental gradient

Prototyping structured decision making for water resource management in the San Francisco Bay-Delta Prototyping structured decision making for water resource management in the San Francisco Bay-Delta

Allochthonous marsh subsidies enhances food web productivity in an estuary and its surrounding ecosystem mosaic Allochthonous marsh subsidies enhances food web productivity in an estuary and its surrounding ecosystem mosaic

Leaf litter decomposition and detrital communities following the removal of two large dams on the Elwha River (Washington, USA) Leaf litter decomposition and detrital communities following the removal of two large dams on the Elwha River (Washington, USA)

Coastal vegetation responses to large dam removal on the Elwha River Coastal vegetation responses to large dam removal on the Elwha River

Framework for facilitating mangrove recovery after hurricanes on Caribbean islands Framework for facilitating mangrove recovery after hurricanes on Caribbean islands

Migration and transformation of coastal wetlands in response to rising seas Migration and transformation of coastal wetlands in response to rising seas

Western Ecological Research Center - Headquarters Western Ecological Research Center - Headquarters

3020 State University Drive

Modoc Hall, Room 4004

Sacramento, CA 95819

United States

Wetland and Aquatic Research Center - Gainesville, FL Wetland and Aquatic Research Center - Gainesville, FL

7920 NW 71st St.

Gainesville, FL 32653

United States

Cooperative Research Units Program Cooperative Research Units Program

12201 Sunrise Valley Dr

Reston, VA 20192

United States

Sacramento Projects Office (USGS California Water Science Center) Sacramento Projects Office (USGS California Water Science Center)

6000 J Street, Placer Hall

Sacramento, CA 95819

United States

Western Fisheries Research Center (WFRC) Western Fisheries Research Center (WFRC)

6505 NE 65th Street

Seattle, WA 98115-5016

United States

Forest and Rangeland Ecosystem Science Center (FRESC) Headquarters Forest and Rangeland Ecosystem Science Center (FRESC) Headquarters

3200 SW Jefferson Way

Suite 400

Corvallis, OR 97331

United States

Land Change Science Program, USGS Ecosystems Mission Area Land Change Science Program, USGS Ecosystems Mission Area

12201 Sunrise Valley Drive

Reston, VA 20192

United States

Lower Mississippi-Gulf Water Science Center - Baton Rouge, LA Office Lower Mississippi-Gulf Water Science Center - Baton Rouge, LA Office

3535 South Sherwood Forest Blvd.

Suite 120

Baton Rouge, LA 70816

United States

Pacific Coastal and Marine Science Center Pacific Coastal and Marine Science Center

2885 Mission Street

Santa Cruz, CA 95060

United States

Science and Decisions Center Science and Decisions Center

12201 Sunrise Valley Drive

Mail Stop 913

Reston, VA 20192

United States

Western Geographic Science Center - Main Office Western Geographic Science Center - Main Office

350 N. Akron Rd.

Moffett Field, CA 94035

United States