Comparing Nearly 40 years of Satellite-derived Shorelines with Traditional Shoreline Measurements

New Tool Revolutionizes Shoreline Mapping with Decades of Satellite Data

A new USGS study compares nearly 40 years of satellite-derived shorelines with traditional shoreline measurements, finding that despite greater uncertainty in any single satellite snapshot, long-term shoreline trends detected from space closely match those captured by more labor-intensive field surveys.

The study, Comparisons of Shoreline Positions from Satellite-Derived and Traditional Field- and Remote-Sensing Techniques, highlights the growing potential of satellite-derived shorelines (SDS) to revolutionize how scientists track coastal change, especially as rising seas and intensifying storms threaten shorelines across the United States.

Traditional shoreline mapping relies on field measurements, aerial photos, and lidar—methods that produce high-quality results but are expensive, infrequent, and geographically limited. Satellites, by contrast, capture coastlines worldwide every few days, offering unprecedented temporal and spatial coverage. Yet questions have lingered about whether SDS are accurate enough to support coastal research and hazard planning along the varied coastlines where USGS works.

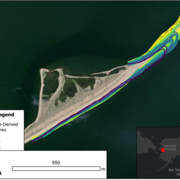

To find out, USGS scientists used CoastSeg, a browser-based tool that automatically detects and maps shoreline positions from satellite images. They ran the software on images spanning 1984–2023 for a range of U.S. coastal settings—from sandy Atlantic beaches to dynamic Pacific shores—and compared the results to shorelines obtained from traditional datasets.

The team found that individual SDS carry higher uncertainty, largely due to image quality, wave effects, and tidal influences. However, when aggregated over decades, the dense time series produced shoreline-change trends similar to those derived from traditional measurements.

“Data quantity is needed to calibrate shoreline change models. Even though the satellite-derived datasets are noisier, the sheer volume of data makes up for it,” said USGS Oceanographer Andy O’Neill, lead author of the study. “With satellites providing tens to hundreds of measurements for every one field datapoint, statistical patterns begin to emerge—the signal is teased out of the noise.”

Attempts to reduce error—such as fine-tuning scalar slopes used to compensate for tides—had only marginal effects on uncertainty. But the consistency of long-term trends suggests that SDS are already robust enough to support many scientific and management applications, from detecting erosion hotspots to forecasting future shoreline positions.

The study also offers practical guidance. Setting up SDS workflows requires significant upfront effort—on the order of weeks to configure software, validate results, and tailor methods to local coastal conditions. But once established, the system can generate new shoreline maps in minutes to hours on an ordinary desktop computer.

These advantages position SDS as a promising addition to the coastal-science toolkit, especially in regions where field data are sparse or too costly to maintain. The authors emphasize that SDS won’t replace traditional methods but can fill important gaps, enabling researchers and planners to monitor coastal change at scales that were previously unattainable.