References:

Auch, R.F., 2015. Chapter 7, northern glaciated plains ecoregion. In Status and Trends of Land Change in the Great Plains of the United States—1973 to 2000, Taylor, J.L., Acevedo, W., Auch, R.F., and Drummond, M.A. pp. 69-76. U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1794-B, Reston, Va.

Baulch, H.M., Elliott, J.A., Corderio, M.R.C., Flaten, D.N., Lobb, D.A., and Wilson, H.F., 2019. Soil and water management: opportunities to mitigate nutrient losses to surface waters in the Northern Great Plains. Environ. Rev. 27: 447–477. https://cdnsciencepub.com/doi/10.1139/er-2018-0101

Blackwell, B.G., Smith, B.J., Kaufman, T.M., and Moos, T.S., 2020. Use of a restrictive regulation to manage walleyes in a new glacial lake in South Dakota. North American Journal of Fisheries Management 40:1202–1215. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/nafm.10486

Damschen, W.C., and Galloway, J.M., 2016, Water-surface elevation and discharge measurement data for the Red River of the North and its tributaries near Fargo, North Dakota, water years 2014–15: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2016–1139, 16 p., https://pubs.usgs.gov/publication/ofr20161139

Hoogestraat, G.K., and Stamm, J.F., 2015, Climate and streamflow characteristics for selected streamgages in eastern South Dakota, water years 1945–2013; U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2015–5146, 35 p., with appendix, https://pubs.usgs.gov/publication/sir20155146

Johnston, C.A., 2013, Wetland Losses Due to Row Crop Expansion in the Dakota Prairie Pothole Region; Natural Resource Management Faculty Publications, 95.https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/nrm_pubs/95/

Liu, G. and Schwartz, F.W., 2011, An integrated observational and model-based analysis of the hydrologic response of prairie pothole systems to variability in climate; Water Resources Research, 47, W02504, https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1029/2010WR009084

NASA, 2020, https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/146515/relentless-floods

Newsdakota.com, 2020, https://www.newsdakota.com/2020/08/07/excess-water-continues-to-plague-prairie-pothole-region/

National Centers for Environmental Information (NOAA), 2025, Climate at a Glance: National Time Series, published May 2025, accessed May 8, 2025, from https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/monitoring/climate-at-a-glance/national/time-series

Nustad, R.A., Kolars, K.A., Vecchia, A.V., and Ryberg, K.R., 2016, 2011 Souris River flood—Will it happen again?; U.S. Geological Survey Fact Sheet 2016–3073, 4 p., https://pubs.usgs.gov/publication/fs20163073

Renton, D.A., Mushet, D.M., and DeKeyser, E.S., 2015, Climate change and prairie pothole wetlands—Mitigating water-level and hydroperiod effects through upland management: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2015–5004, 21 p., https://pubs.usgs.gov/publication/sir20155004

Ryberg, K.R., Vecchia, A.V., Akyüz, F.A., and Lin, W., 2016, Tree-ring-based estimates of long-term seasonal precipitation in the Souris River Region of Saskatchewan, North Dakota and Manitoba, Canadian Water Resources Journal / Revue canadienne des ressources hydriques, 41:3, 412-428, 17 p., https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/07011784.2016.1164627

Shapley, M.D., Johnson, W.C., Engstrom, D.R., and Osterkamp, W.R., 2005, Late-Holocene flooding and drought in the Northern Great Plains, USA, reconstructed from tree rings, lake sediments and ancient shorelines. The Holocene, 15 (1): 29-41.

Todhunter, P.E. 2018, A volumetric water budget of Devils Lake (USA): non-stationary precipitation–runoff relationships in an amplifier terminal lake. Hydrological Sciences Journal, vol. 63 (9):1275–1291. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02626667.2018.1494385

Todhunter, P.E., 2021, Hydrological basis of the Devils Lake, North Dakota (USA), terminal lake flood disaster. Nat Hazards 106, 2797–2824 (2021). https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11069-021-04567-2

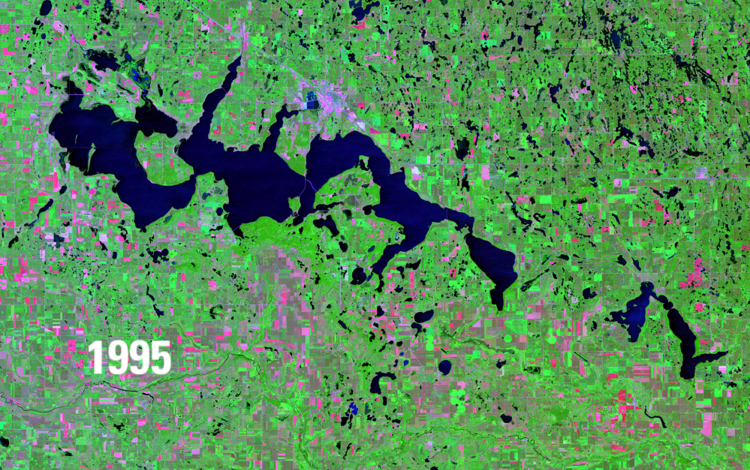

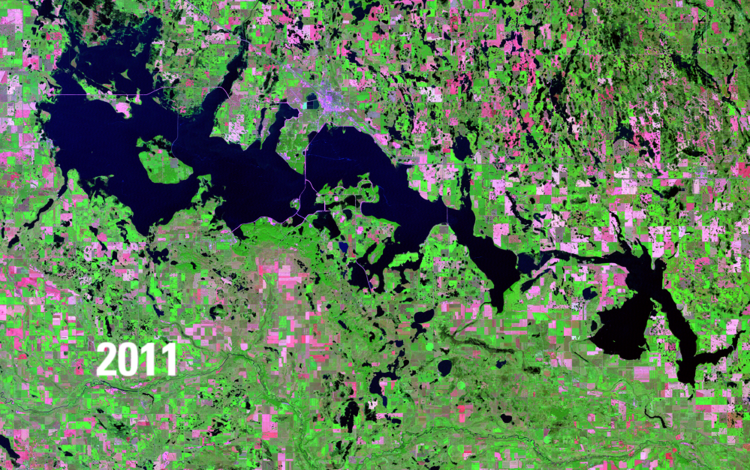

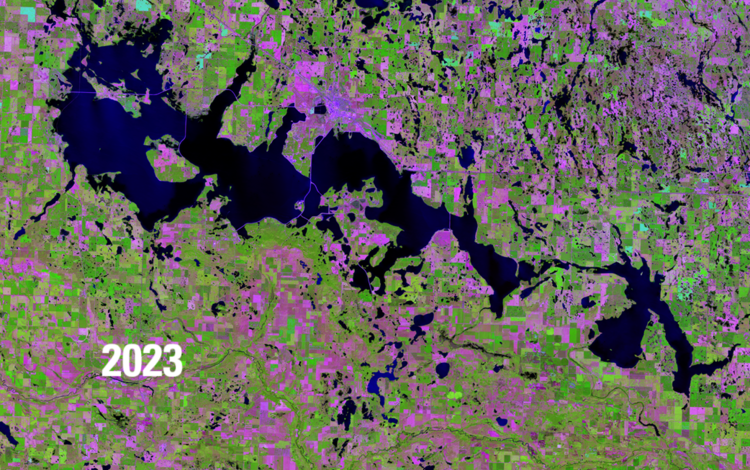

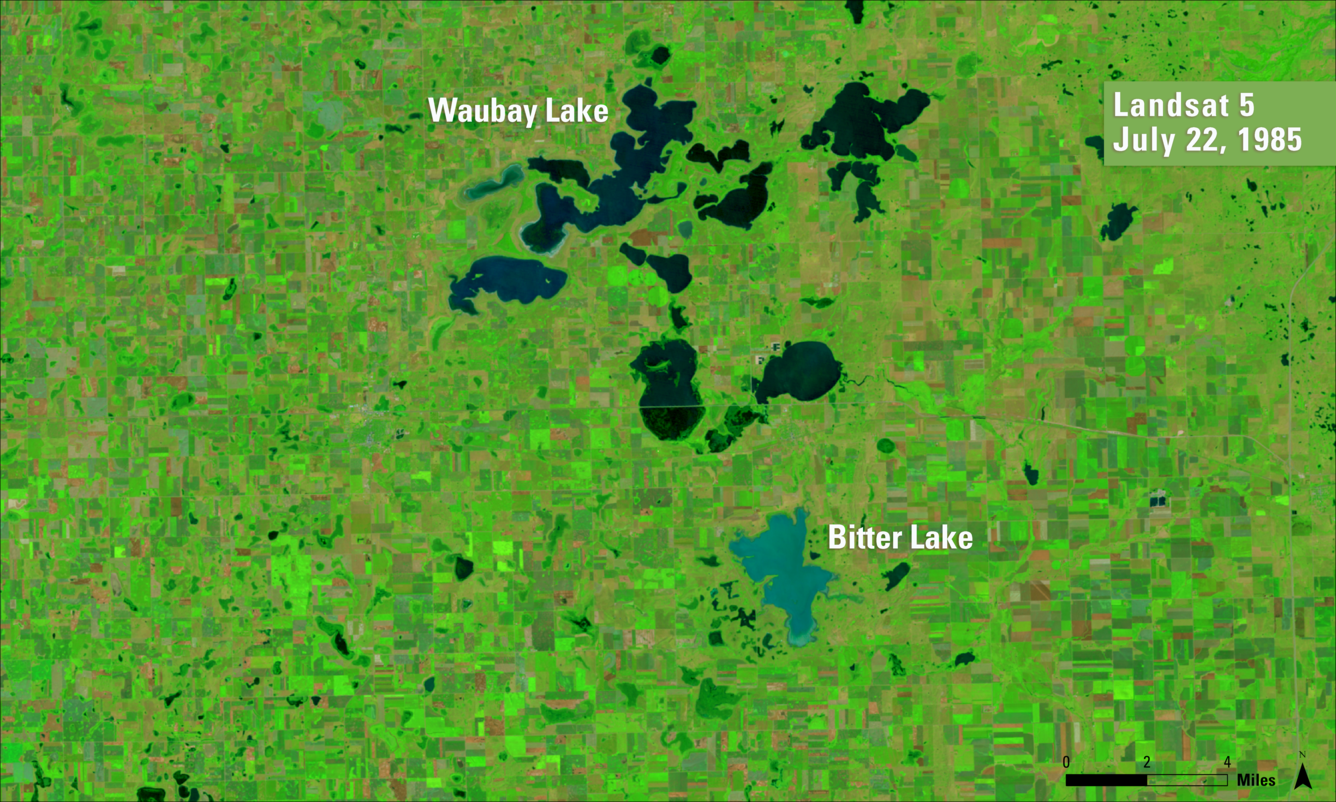

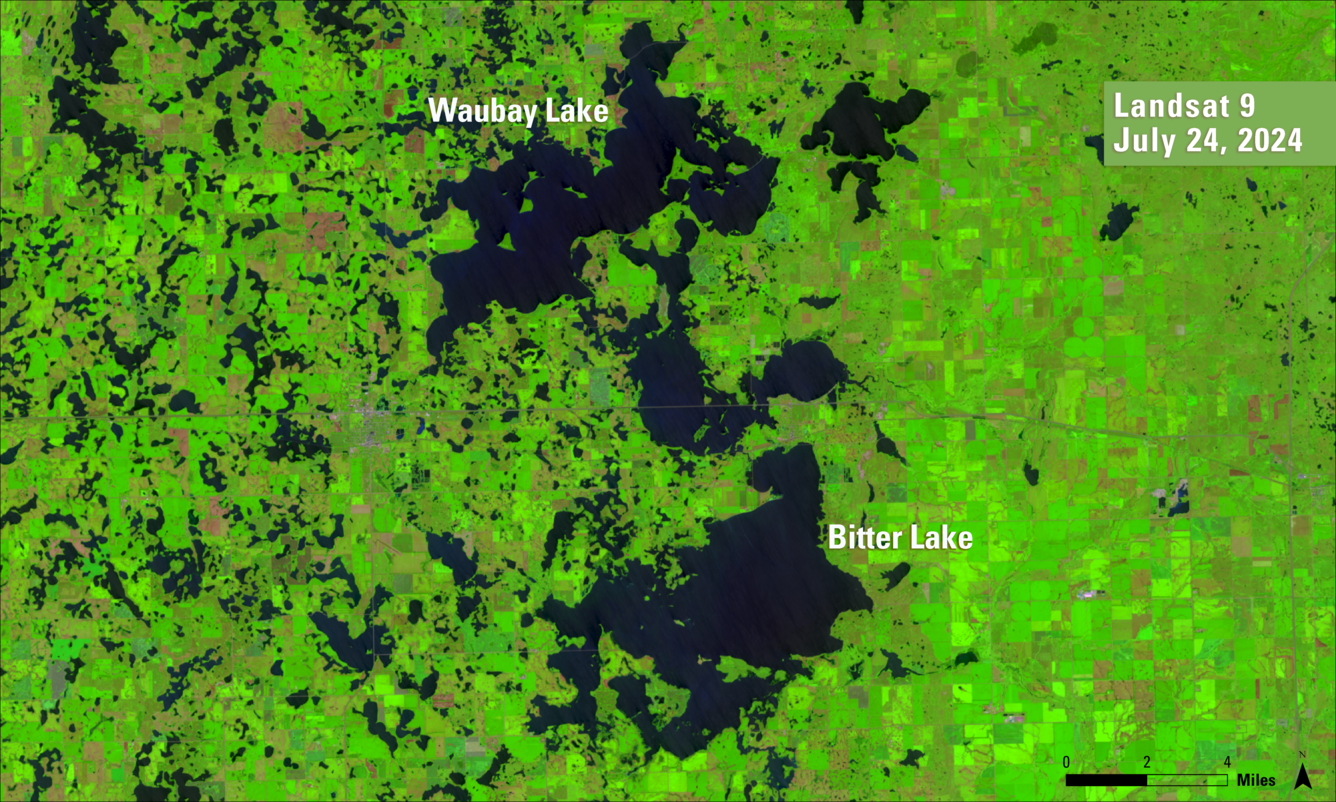

USGS Earth Resources Observation and Science (EROS) Center, 2022, Lake levels rise: U.S. Geological Survey Earthshots webpage, 2022, accessed online 6/26/2025, at https://eros.usgs.gov/earthshots/lake-levels-rise

Vanderhoof, M.K., Alexander, L.C., and Todd, M.J., 2016a, Temporal and spatial patterns of wetland extent influence variability of surface water connectivity in the Prairie Pothole Region, United States; Landscape Ecology 31, 805–824 (2016). https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10980-015-0290-5

Vanderhoof, M.K., and Alexander, L.C., 2016b, The Role of Lake Expansion in Altering the Wetland Landscape of the Prairie Pothole Region, United States; Wetlands 36 (Suppl 2), 309–321. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13157-015-0728-1

Vanderhoof, M.K., Christensen, J.R. and Alexander, L.C., 2017, Patterns and drivers for wetland connections in the Prairie Pothole Region, United States; Wetlands Ecology and Management 25, 275–297. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11273-016-9516-9

Vecchia, Aldo V., 2011, Simulation of the effects of Devils Lake outlet alternatives on future lake levels and water quality in the Sheyenne River and Red River of the North; 2011; SIR; 2011-5050.

Wimberly, M.C., Janssen, L.L., Hennessy, D.A., Luri, M., Chowdhury, N.M., and Feng, H., 2017, Cropland expansion and grassland loss in the eastern Dakotas: New insights from a farm-level survey; Land Use Policy, Volume 63, Pages 160-173.